Artists going down ▼

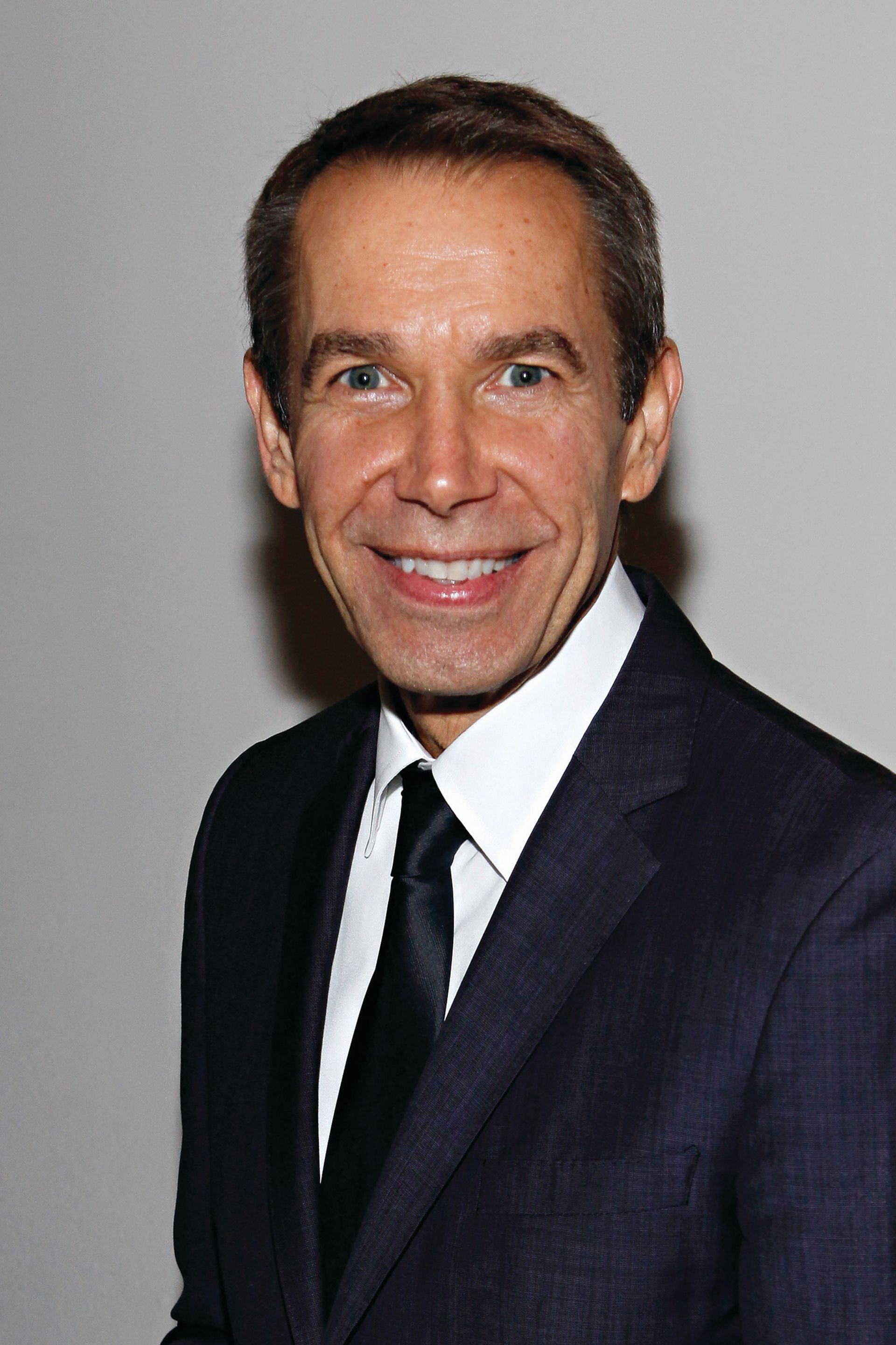

Jeff Koons

Following the damp squibs that Jeff Koons showed at David Zwirner in 2013—

plaster casts, from the Classical to the trashy, accompanied by gazing balls made from blue glass—have come related works at Gagosian Gallery, in which these handblown garden decorations stick out on aluminium shelves from painted reproductions of masterpieces by Turner, Titian, El Greco, Manet and more. “These paintings are stronger being together with the gazing ball,” he says. “If you take away the gazing ball, they don’t have the same power. They don’t have the same phenomenology taking place. These paintings are masterpieces in their own time, but in this time, this moment, they’re most powerful in this state, with this gazing ball.” A satirist of art-world hubris couldn’t have put it better.

Anish Kapoor

The appalling anti-semitic graffiti daubed on Dirty Corner, Anish Kapoor’s sculpture at Versailles, detracted from the fact that, characteristically for his grand public gestures, it lacks the sensuality and mystery of top-notch Kapoor. But it’s a masterpiece compared with the meaty, bodily deep-red silicone paintings that the artist showed at London’s Lisson Gallery in March. Right now, these paintings hang in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum with Rembrandt’s late works (until 6 March), taking the sublime/ridiculous binary to new heights.

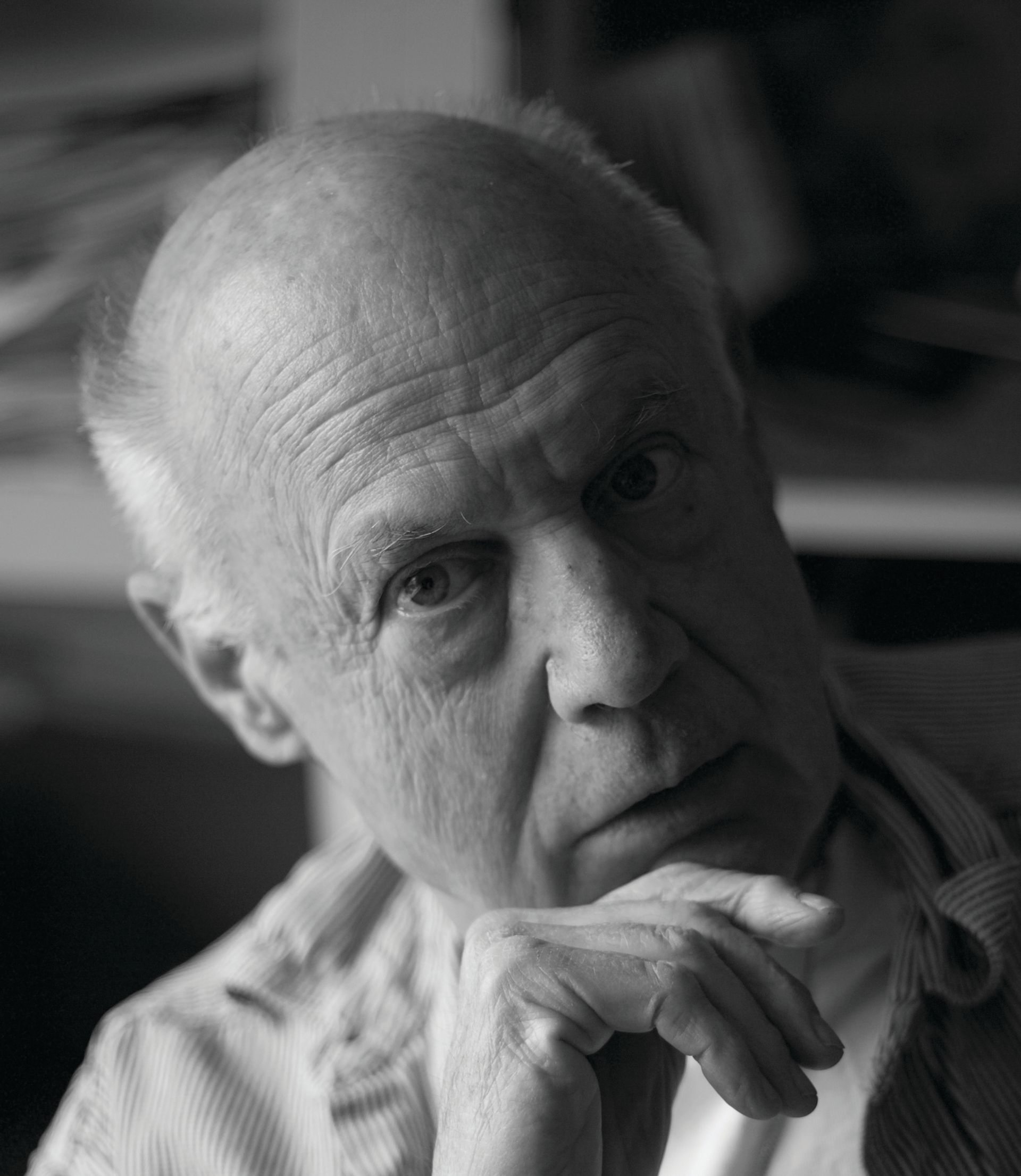

David Hockney

Often a perceptive judge of optical and pictorial elements, David Hockney took on perspective in photography at London’s Annely Juda Fine Art this spring, collaging together extreme close-ups of people and objects in Photoshop to create “an almost 3D effect without the glasses”, he said. An admirable ambition, but these “photographic drawings” were a repetitive mess (and the Photoshopping particularly clumsy). Meanwhile, 79 of his recent bland portraits will fill the Royal Academy of Arts next summer. This latest phase of Hockney’s long career is blighted by a characteristic we never expected from him: dullness.

Martial Raysse

Hands down, the winner of the biggest turkey at the Venice Biennale was Martial Raysse’s show at the Palazzo Grassi. His narrative paintings, produced since the 1970s, surely rank among the most horrible works ever made, and yet references to the Renaissance and to Poussin, among others, are lazily tossed out by Raysse’s supporters. Chief among the latter group is François Pinault, the artist’s principal collector and the owner, of course, of the Palazzo. Raysse says that Pinault “had been telling the world I was a good artist for so long that in the end, people started to believe him”.

Damien Hirst

Hopes of a relative absence of new work by Damien Hirst in 2015 were dashed by two paintings on sale on White Cube’s stand at Frieze London in October. Holbein (Artists’ Watercolors) (2015) blew up a colour chart by an art materials company—at once a lame reference to Gerhard Richter’s colour chart paintings (Hirst is a huge fan), a tired nod to his own spot paintings and a banal rendering of a Duchampian found object. Super Centre (2014), meanwhile, is a small painting featuring a grid of colourful corporate logos. Need we say more?

Artists on the up ▲

Ron Nagle

As young artists working with ceramics (such as Jesse Wine and Aaron Angell) begin to make an impact in the art world, it’s fitting that Ron Nagle, fresh from a telling contribution to the Venice Biennale in 2013, should have one of the shows of the year in his mini-retrospective of the past 25 years at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York. Tiny and loaded with colour and sensory and textural delight, Nagle’s works channel everything from Philip Guston to Krazy Kat to Giorgio Morandi, and marry the dazzle of exquisite jewels with the gravitas of great art.

Chris Ofili

Close to a decade after definitively ditching his trademark elephant dung, Chris Ofili has hit his stride in his most recent works. After a justly acclaimed show at the New Museum at the end of 2014—a triumphant return to New York, the city he was almost hounded out of in the furore over his Holy Virgin Mary in the Sensation exhibition (1999-2000)—Ofili created one of the highlights of Okwui Enwezor’s Venice Biennale, with a four-painting installation at the Arsenale. His resurgence is an object lesson in allowing artists to find their way without the pressure to overproduce; dealers, take note.

Rachel Rose

Few debut museum shows can have been as confident as Rachel Rose’s exhibition at London’s Serpentine Sackler Gallery. She filled the narrow promenade with atmospheric directional sound that pulled visitors into two entrancing video installations, which teemed with visual power and evocative references to everything from cataclysmic hailstorms captured on YouTube to Poussin and the American Revolutionary War. Her current shows, at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and the Castello di Rivoli in Turin, share this ambitious quest for sensory and cerebral immersion.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

It would be unfortunate if the sudden leap in Yiadom-Boakye’s market prices—a 2011 painting sold at Christie’s for £446,500 in October, against an upper estimate of £80,000—

resulted in the artist being grouped with the less talented market darlings of recent years. Yiadom-Boakye is the real deal: a painter of fictional portraits, mainly of black men and women, often in enigmatic groupings and gloomy settings. As this year’s shows at the Serpentine in London and Munich’s Haus Der Kunst proved, she uses paint with such flair that almost every work enthrals. Yiadom-Boakye achieves the winning combination of a vivid sense of life in her subjects and liveliness in her handling of them.

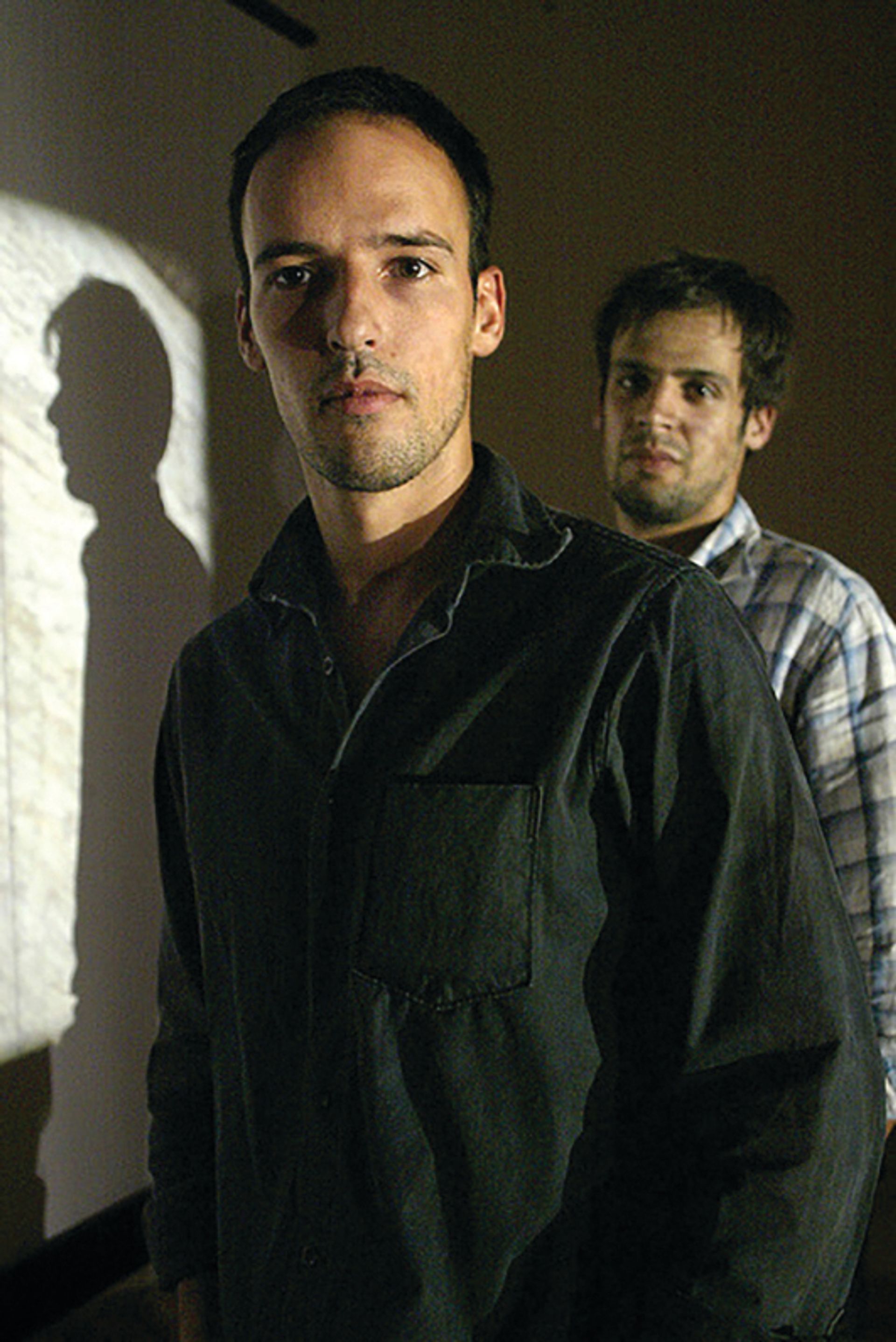

João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva

In an art world where longer-form videos are increasingly the norm, the films of João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, often shown in sculptural environments, are a welcome short, sharp shock. Their show Papagaio, seen in Milan, London and Berlin, was a genuinely immersive world of films shot on high-speed cameras and then projected in slow motion. As projectors whirred, the imagery echoed and rippled; even mundane details, such as a blind man eating a papaya, proved utterly transfixing, with each work resembling a slowly evolving, richly detailed painting.