Dorothy Cross: Eye of Shark, Frith Street Gallery (until 23 December)

From her vantage point on Ireland’s wild west Connemara coast, Dorothy Cross conjures up magical, ritualistic works that dissolve the boundaries between nature, culture, religion and superstition to haunting and memorable effect. Rows of rusting iron baths fill part of the gallery with what looks like an ancient burial site, each with a careful band of gilding replacing the accumulated residue of scummy watermarks. They also resemble an assembly of worshippers, arrayed before a tiny reliquary set into the wall and containing—so we are told—the eye of a shark. There’s also a shark on the floor, cast in bronze, and the skin of another, coated in silver gilt and propped on an easel. But although these make for dramatic objects—as any swimmer (or Steven Spielberg) will confirm—these most feared creatures exert the most power when unseen, lurking within the imagination or, in the case of this show, when all their primeval energy and balefulness is contained and concealed within a tiny box.

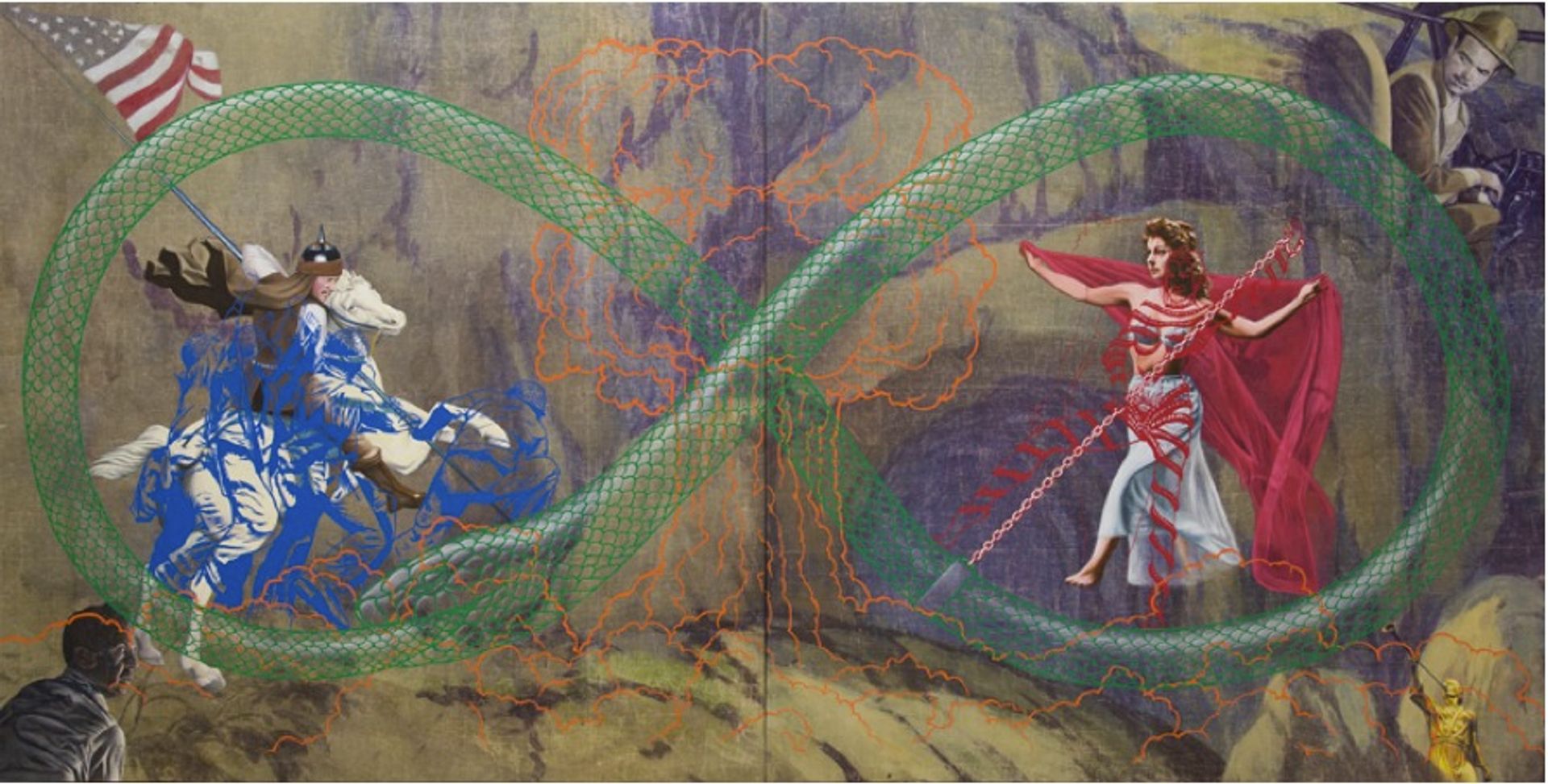

Jim Shaw, Simon Lee Gallery (until 8 January 2016)

It is appropriate that these most recent paintings by the thrift-store scavenger, king of contemporary Americana, are themselves painted on salvaged scenic backdrops from the theatre and early movies. Against these, Shaw’s bizarre and often arcane musings on the myriad histories and mythologies of popular American culture are given extra depth and patina. Playing out against a backdrop that is already part of entertainment history is especially apt in his ‘St George and the Dragon’ (2015), a madcap blend of art, religion and the movies in which the main protagonists are John Wayne playing Genghis Khan and Susan Hayward as a Tatar princess, presided over by a toxic nuclear setting by a furtive Howard Hughes. Other lurid, but also wonderfully plausible and visually arresting mash-ups, include Edward Snowden cast as Prometheus, surrounded by model drones and the Jolly Green Giant who steps off the sweet corn can to be recast as the third avenging angel from the Book of Revelation, while pouring forth gorily toxic GMO tomato sauce onto unsuspecting pastoral surroundings.

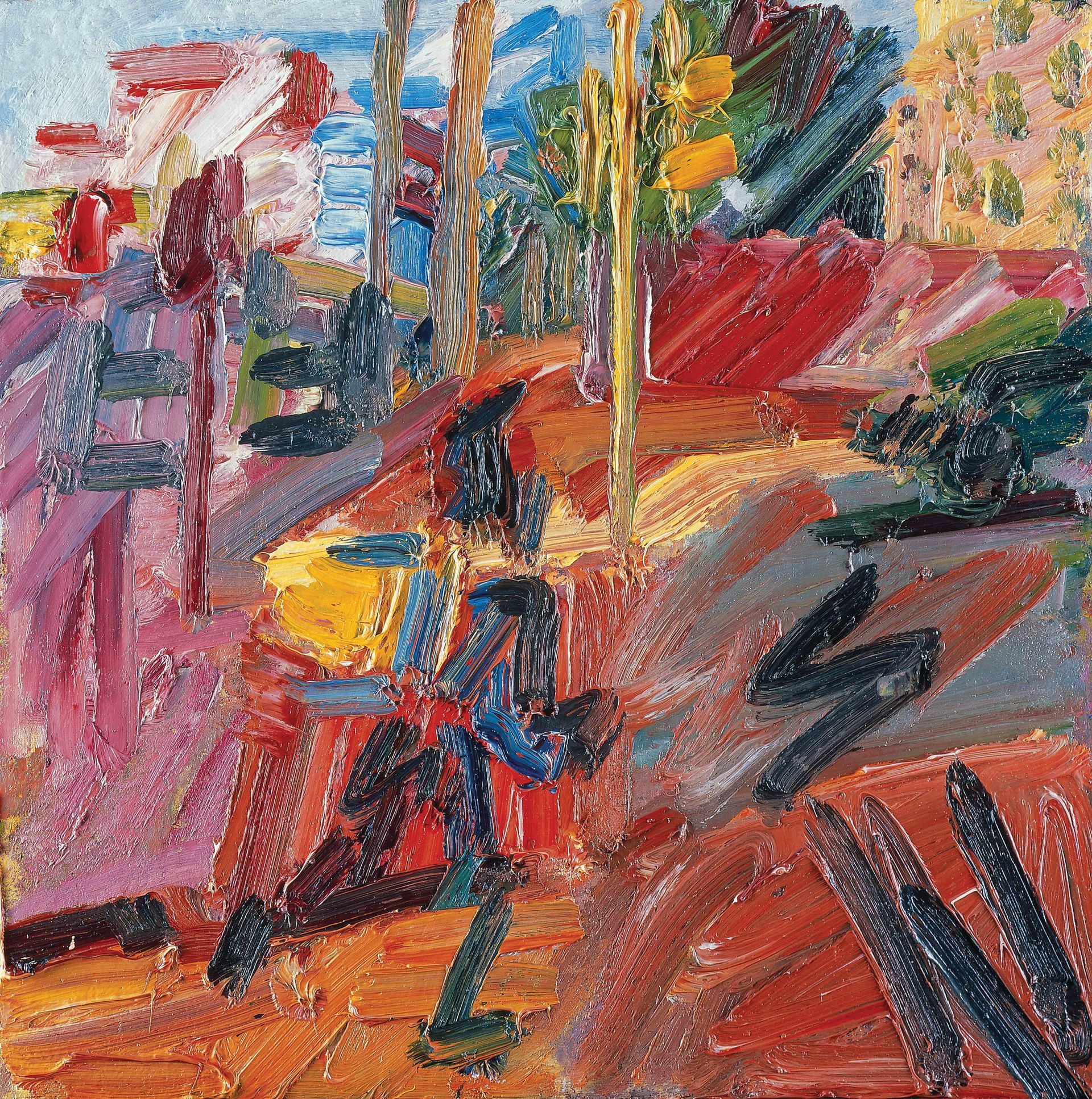

Frank Auerbach, Tate Britain (until 13 March 2016)

Never has the dictum “paint what you know” seemed more apposite than in the case of Frank Auerbach, who for over 60 years has repeatedly revisited the heads of a few sitters and the streets of London, especially those around his studio in Mornington Crescent. Yet as this rich and rewarding exhibition confirms, what we think we see and know is forever in a state of flux. The same subject and the same vantage point can often result in a completely different work and if ever there was a show which confirms the mini-miracles that paint can perform it is this one—if you are prepared to take the time for them to do so.

Living, breathing or sometimes uncannily skull-like heads slowly emerge, Golem-like, from inches-thick wodges of paint, or are whipped up from the slimy skids and swirls that, when viewed from the right distance and angle, shudder utterly convincingly into life. Similarly, a grimy, ugly, energetic London—whether blighted by 1950s bombsites or the building-boom noughties—reverberates from often surprisingly vivid blocks and bars of paint. Six rooms, one for each decade, have been predominantly sel ected by the artist, with a final room put together by Catherine Lampert, one of his most enduring sitters and longstanding chroniclers. The result is an utterly satisfying experience of faces and places seen through a constantly fresh eye.

Susan Hiller: Lisson Gallery (until 9 January 2016)

For her Lisson Gallery debut, Susan Hiller takes over all the spaces across both gallery sites with a rich spread of work spanning from the late 1960s to this year. But this is no ordinary chronology, with much of her multifarious output reframed, recontextualised and rebooted to strike up new conversations across the decades, confirming that Hiller’s unconventional investigations into how the paranormal and the supernatural work with systems of both belief and art, are as fresh and relevant as ever. Whether in her earliest quasi-anthropological hand prints, automatic writing group projects or altered photo booth self-portraits; the hand-dyed monochrome canvases recycled and restitched into minimalist grids; or the more recent collections of German pottery or Beuysian first-aid cabinets filled with phials of holy water. And right up to her newly created grids of prints using—and revisiting—found postcard images of stormy seas, we are yet again reminded that there are no boundaries between the rational and irrational, and that the making and the viewing of art are each processes that require a powerful leap of faith from both artist and audience.