In any Venice Biennale year, it is inevitable that all eyes focus on La Serenissima for clues as to how art will develop over the coming years. But although the previous edition, in 2013, set an agenda that we have seen played out over the past two years—the increasing presence of Outsider artists in museums being the most notable influence—it is not quite as straightforward to predict what traits from Okwui Enwezor’s 2015 exhibition will act as bellwethers for the imminent future of contemporary art. This is partly due to the fact that much of Enwezor’s show, All the World’s Futures, was a continuation of his far more radical Documenta exhibition of 2002. It was dominated by geopolitical work (especially video), diverse in ethnicity, heavy on the theory and infused with documentary and archival practices.

Although the centrepiece of Enwezor’s show—the daily, solemn, ill-attended live readings of Karl Marx’s Das Capital—seems unlikely to be repeated, socially and politically minded art looks set to dominate the international agenda for some time, albeit perhaps not at the evening auctions.

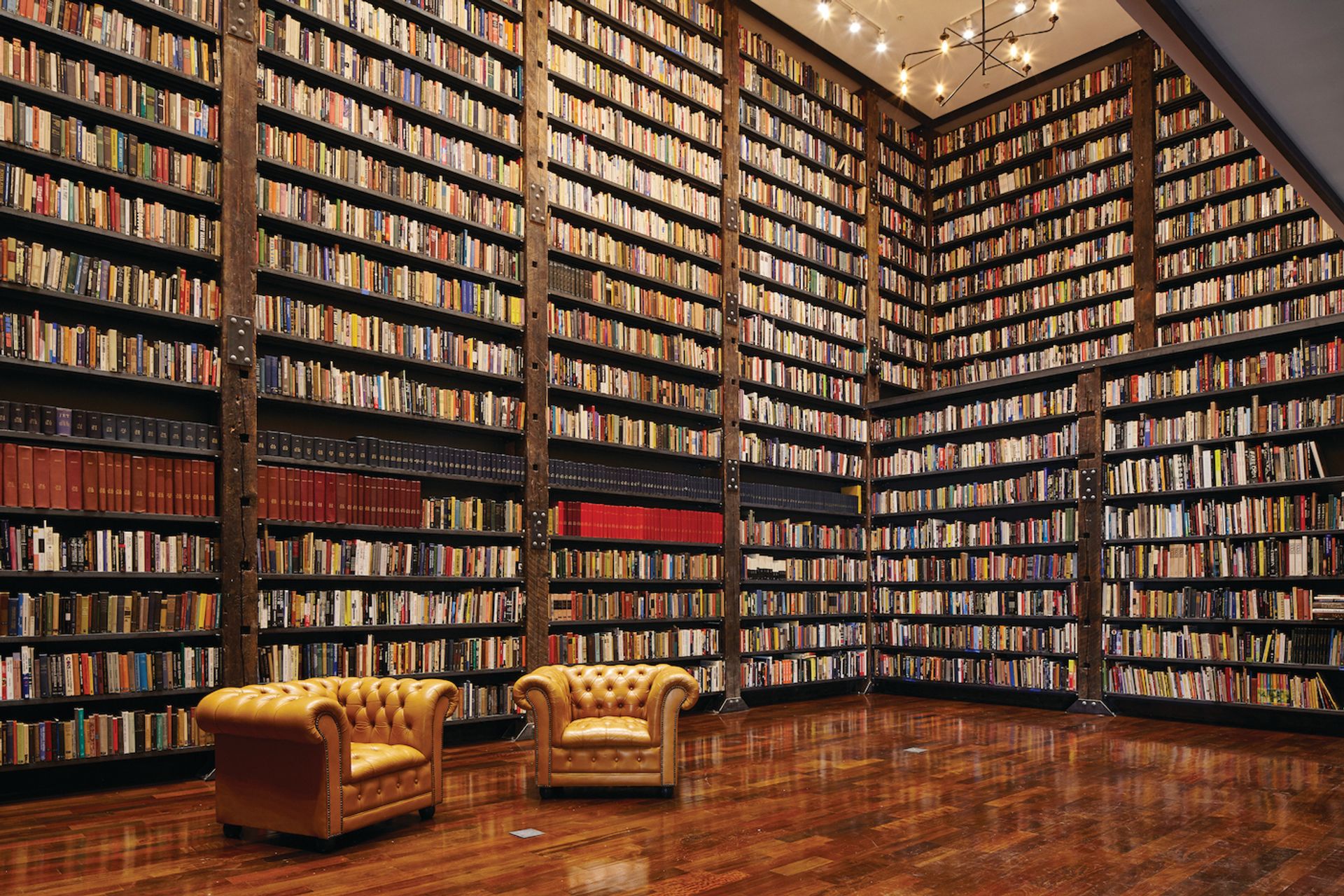

Theaster Gates, the US activist and artist who transforms underprivileged districts of Chicago while also maintaining a prominent position within the blue-chip halls of White Cube gallery, is emblematic of one strain of this deeply engaged form of work. Social practice art, of which Gates is the best-known example, has grown in presence—so much so that Assemble, a UK-based collective that works with local communities on architecture projects, found its way onto this year’s Turner Prize shortlist.

One shift seems notable: the artists Enwezor invited to Venice used a significantly broader range of media than those in his Documenta show, which was very heavy on video. In this, at least, the exhibition reflected the sheer variety in artistic practice in 2015. The fact that figurative painting, through the works of artists like Chris Ofili and Kerry James Marshall, featured prominently in All the World’s Futures reflects the enduring opening-up of media across the art world. Even disciplines previously dismissed as craft, such as ceramics, are enjoying far greater prominence than in previous decades. Perhaps now more than ever, all media are equal in the visual arts; that has to be a good thing.