The vast expanses of the American Southwest became the preferred canvas for a group of artist-explorers, who, from the late 1960s, traded the confines of the traditional gallery space for a literally groundbreaking type of art carved directly into the landscape. Although it was a global phenomenon, with artists such as the UK’s Richard Long creating land pieces at around the same time, it is the works in the US—such as Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), a 1,500ft-long mud and rock piece in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, and the awe-inspiring Double Negative (1969-70), which Michael Heizer created by removing 218,000 tonnes of rock to cut two massive trenches between two mesas in the Nevada desert—that have come to exemplify the movement.

A new film by James Crump, Troublemakers: the Story of Land Art, focuses on these early years, looking at seminal works by Heizer, Smithson and Walter De Maria—artists who have been referred to as the triumvirate of Land Art. It is due to be screened at Art Basel in Miami Beach today (The Colony Theatre, 1040 Lincoln Road, Miami Beach, 8.30pm screening followed by Q&A with the director and Marian Masone. Doors open at 7:30 pm. Admission is free but seating is limited.).

A new generation of artists is engaging with the earth and the legacy of the Land Art movement. Ben Tufnell, the author of the book Land Art (2006) and the co-director of the London gallery Parafin, which recently staged a show of works by Nancy Holt, says that early Land Artists such as Holt had concerns similar to those of artists today, particularly in regards to ecology. “The environment is absolutely a central issue in today’s media,” he says. The news is filled with reports about deserts expanding, icecaps melting and sea levels rising. Indeed, the UN climate-change summit (COP 21) now taking place in Paris is one of the most talked-about political-environmental events of recent years, with many artists, including Olafur Eliasson, staging environmental art installations to coincide with the conference. Today’s artists are responding to “this yearning for a reconnection with ideas of nature”, Tufnell says.

For some artists, the influence of these early Land Art projects is obvious. The California-based artist Jim Denevan’s temporary earth works on sand and ice are reminiscent of Spiral Jetty and a work Heizer created by riding a motorcycle in circles on a dry creek bed in Nevada in 1970. Like Heizer, whose father was an archaeologist, the Australian artist Andrew Rogers is influenced by ancient societies; he has created a series of monumental geoglyphs on seven continents called Rhythms of Life. For the self-taught artist Ra Paulette, who has spent 25 years hand-carving massive caves into the limestone mesas of New Mexico, his “wilderness shrines” are social and environmental projects.

The landscape is central to a new work by Allora & Calzadilla, Puerto Rican Light (Cueva Vientos), which was installed in a remote cave on the Caribbean island in September. The two-year installation, co-commissioned by the Dia Art Foundation—a long-time supporter of Land Art—uses solar power to light a work by Dan Flavin that is installed in the cave. “This is very different from their other work in terms of scale and idea,” says Dia’s assistant curator Kelly Kivland. Christoph Büchel’s proposed project Terminal, which involves burying a Boeing 727 in the California desert, has been in the works since 2000. The UK artist Roger Hiorns also plans to bury a jet plane, in his home city of Birmingham in England’s Midlands. Hiorns hopes that his Boeing 737 will be interred by 2017.

For others, the link to the land is not immediately apparent, but it is still central to their work. The abstract canvases made by Ayan Farah have the imprint of the landscape embedded in them, because her process involves either burying pieces of canvas in the earth or exposing them to natural or UV light to bring about organic or chemical changes. The Scottish artist Katie Paterson creates time- and space-themed works that remind us just how small we are in the universe. “Her work gives a sense of this dizzying perspective, almost as if you’re seeing yourself from the wrong end of a telescope,” Tufnell says. It is connected to Land Art in terms of its sensibility. “It’s finding new ways to engage in ideas about art, nature and our relationship with nature.”

Joy Sleeman, a reader in art history and theory at University College London’s Slade School of Fine Art, says that the more interesting works resulting from this legacy are not necessarily large-scale outdoor works. “They are often ones that show an attitude change in our relation to our terrestrial relationships,” she says. Kivland says that young artists have a romantic view of these pioneers, whose work received an “unparalleled” amount of financial support from Dia and others. “This way of working and the means of support are things that artists are looking at again as an alternative to the market and this push for production. Given that we’re talking about this in the context of Art Basel, I think it’s a really important conversation,” she says.

Artists with land in sight

James Turrell

Like Michael Heizer’s sprawling City, in Nevada, and Charles Ross’s Star Axis, in New Mexico, James Turrell’s Roden Crater is still a work in progress almost 40 years after the project began. The Light and Space artist bought an extinct volcanic cinder cone in the Arizona desert in 1979 with an idea to create a controlled environment for experiencing and contemplating light. The Skystone Foundation, a non-profit organisation founded to support the project, recently named Yvette Lee as its new executive director. It is currently fundraising for the project’s final phase.

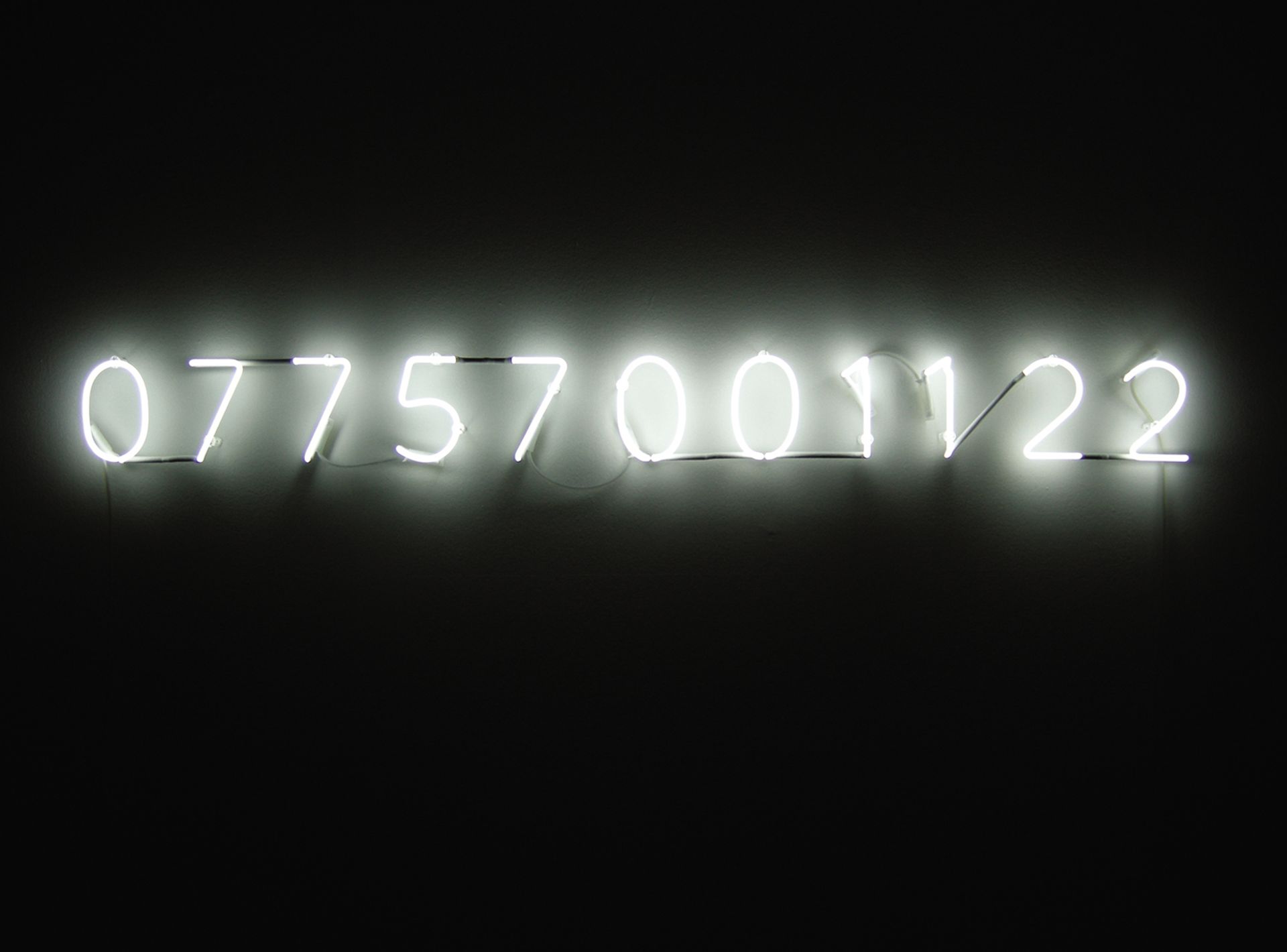

Katie Paterson

The Scottish artist’s science-based work is connected to Land Art in its sensibility of finding new ways to engage with nature. For her degree show at London’s Slade School of Fine Art, she presented Vatnajökull (the sound of) (2007), which consisted of a phone number in neon that linked to a phone under an Icelandic glacier—callers could listen to the glacier melting live. For Campo del Cielo, Field of the Sky (2013), Paterson took a cast of a meteorite, melted it down and recast it in exactly the same form.

Ayan Farah

The Sharjah-born artist uses mud, clay, ash and water to create her abstract works, which have been called “forensic paintings without the paint, and composed by forces larger than her own hand” and “patchwork canvases with the stained, sewn-together memories of a landscape”. They become records of time and place. A few years ago, Farah travelled to a volcano in Iceland that was on the verge of eruption to bury her sleeping bag liner; she retrieved it six months later.