Trevor Paglen goes after subjects that are normally out of sight: the CIA, the NSA, spy satellites, military drones, internet surveillance. The resulting work is similarly abstracted: hazy photographs of national security agencies’ headquarters, lists of codenames for classified military programmes and a sculpture that doubles as a router to anonymise internet traffic. As well as an MFA in fine art, Paglen has a PhD in geography, which has informed how he seeks out the invisible structures that have an impact on contemporary society.

This week, Paglen is due to lead a diving trip to visit the underwater internet cables near Miami that were tapped by the NSA – an example of what he calls “experimental geography”. He will also take part in a talk with fellow artist Jenny Holzer and the writer Kate Crawford, a founding member of New York’s Deep Lab, at Art Basel in Miami Beach. He is represented at the fair by Metro Pictures, New York (E1).

The Art Newspaper: The Miami project came out of a larger project that you’ve done, looking at the underwater cables that were tapped by the NSA.

Trevor Paglen: The origins of that project are with Citizenfour, the documentary film that Laura Poitras made about Edward Snowden. I have a history of researching secrecy—looking at the CIA and satellites and things like that. Laura asked whether I would work on the research side of the film and how we could generate images to communicate this—the landscape and technical programmes that are unfamiliar to us. And one of the things that Snowden and another NSA whistleblower, William Binney, were going on and on about was landing sites. I didn’t even know what the hell a landing site was, but they were really underlining the importance of these places.

We think of the internet as the cloud or cyberspace, or this very misty everywhere-and-nowhere kind of thing. But that’s not at all how the NSA thinks about it, and that’s not how it works, actually.

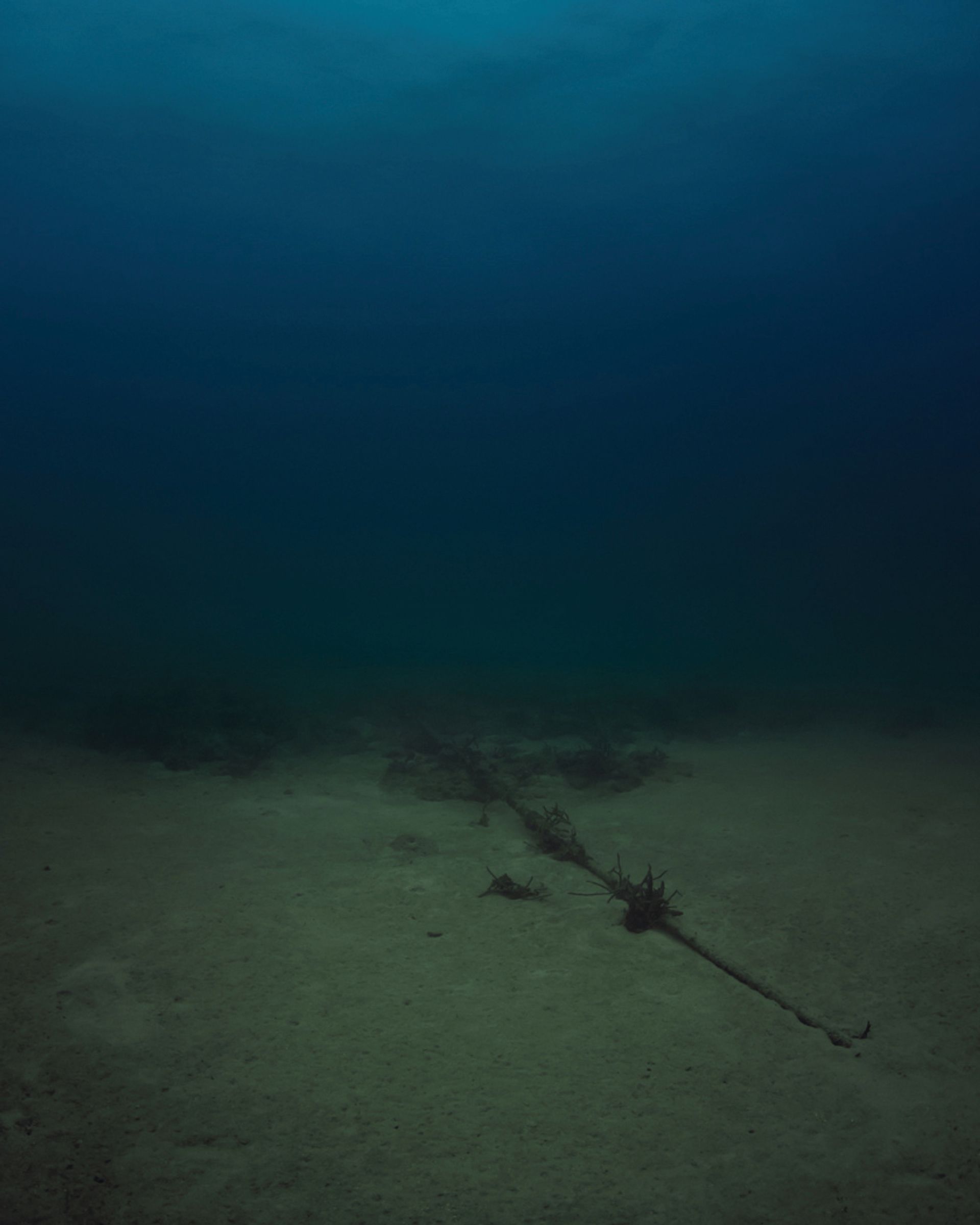

The internet is an exquisitely material thing. All of the continents are connected to each other, literally, by cables that lie at the bottom of the ocean. There’s a cable that connects the US to Europe—there are dozens of them, actually—and the US to South America. Something like 90% of the world’s data traverses those cables. And there are specific places where the UK is connected to the US, where the US is connected to South America and Japan and Australia. There are around 10 of these places in the US, and three or four—major ones—are on the East Coast, where all the fibre-optic cables come together at certain points.

So these landing sites are very juicy targets for anybody who wants to tap the world’s internet, because so many cables come together in one place, and you can see everything that goes in and out of the US.

It’s a jugular vein for information.

Exactly; that’s why they’re important to surveillance. So I started going to these places and just photographing them, shooting video—and there’s nothing to see, because it’s all underwater.

I’ve done many projects about that. I take a picture of something that’s vastly important, that has enormous consequences in terms of human lives, and it’s actually invisible. A lot of the work I’ve done throughout my career is trying to photograph that invisibility. People say I’m interested in exposing invisible things. That’s not actually true; what I’m trying to expose is invisibility itself.

Is this where “experimental geography” becomes relevant?

The experimental geography provocation was initially aimed more at academics and scholars, but, interestingly, artists found it more useful, because it’s basically about a relationship between form and content, which is what we obsess about as artists.

It’s being aware of the specificities of the medium I’m working with, and what different media can do well, and expanding the idea of medium in the first place. This scuba-diving trip that we’re doing in Miami is very much an example of that. I can make a picture and I can put it on a wall, and we can look at it and talk about it. But what if we make this an expedition? What if we activate bodies and bring people to look at a landscape, rather than making a representation of a landscape?

You’ve been following these surveillance systems for a while. Have you noticed any changes?

I hate to sound cynical, but I’m more worried about it now than I’ve ever been. In the early and mid-2000s—when [security agencies] were setting up much of what is now the mass surveillance infrastructure, and the CIA was setting up Guantanamo Bay and black sites and enhanced interrogation/torture programmes that evolved into assassinations—common sense dictated that these were aberrations. It’s not normal to be assassinating people. It’s not normal to be torturing people. It’s not normal to be mass-surveilling people.

Those programmes have become much more normalised; not only culturally, but also legally and politically. If you did a survey in 1995 and asked, “Should the US torture people?”, I bet the vast majority would have said, “No, that’s ridiculous; it’s so far off the charts that it’s inconceivable.” If you asked that question now, you would get a much higher percentage of the population saying that we should.

And under the Obama administration, more whistleblowers have been prosecuted than under all previous administrations combined. So there’s a climate of real fear among journalists who are looking at this stuff, which didn’t exist before—not even during the Bush years. The combination of those things is pretty troubling, and many people don’t think much about what the implications are for society as a whole.

• Artist Talk, Trevor Paglen and Jenny Holzer (with Kate Crawford), Miami Beach Convention Center, Thursday 3 December, 10am-11.30am

From deep sea cables to nuclear disasters

Trinity Cube is “one of my favourite projects but, ironically, nobody can really see it”, Paglen says. The work is part of Don’t Follow the Wind, an exhibition installed in abandoned buildings in the Fukushima exclusion zone. The high levels of radiation at the nuclear disaster site in Japan mean that works by international artists including Chim-Pom, Eva and Franco Mattes, Ai Weiwei, Taryn Simon and Paglen will not be seen by the public until the area is declared safe. “That could be in three years, or it could be in 30,000 years,” Paglen says. “You’re making a work that exists on a very different timescale than it would for a traditional museum.” His object is a cube made of irradiated glass found on the ground in Fukushima, which was melted down around a core of trinitite. “That was created when the Manhattan Project exploded the first nuclear bomb in New Mexico in 1945. The explosion was many times hotter than the surface of the sun, and it turned the whole desert into glass,” Paglen says.