This handsome and substantial volume, visually sumptuous and intriguingly diverse in its sources, is not, strictly speaking, an art book. Apart from the portraits, the illustrations are botanical, horticultural, entomological, topographical and technical, along with garden plans and prospects (from the elegant masters of this genre, Thomas Robins the Elder and Younger), and even embroidery—inevitable where Mrs Delany is involved, and from the joint editor of Mrs Delany and Her Circle (Yale, 2009).

A succession of set pieces, arranged chronologically, investigate specific sites of which the author has either fresh archival or practical hands-on experience (as adviser at, for example, John Evelyn’s lost garden, the restored gardens at Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, and at Painshill Park). The story moves from the “little ice age” in Evelyn’s lifetime, to the great storm of 1703, the exceptionally hot summer of 1783, and the storms of the late 18th century that brought devastation to the gardens at Badminton and Bulstrode.

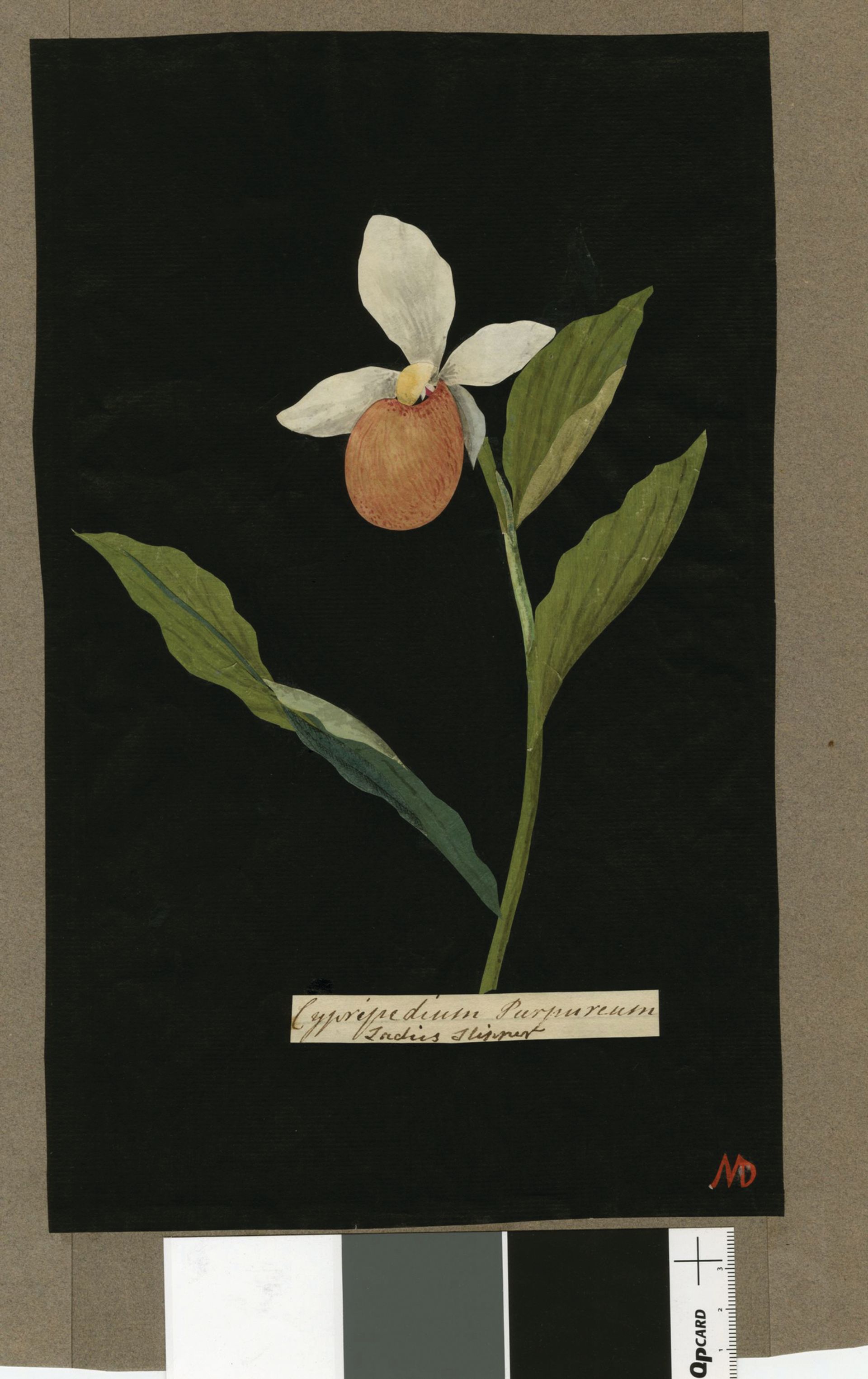

Evelyn and his garden at Sayes Court in Deptford are the main focus of chapter 1, along with the frost fair of 1683-84. Mark Catesby is a key figure in chapter 3; his experiments in acclimating plants from his voyage to South Carolina brought many new species into cultivation in Britain. Chapter 4 involves Georg Dionysius Ehret and the Robinses, father and son, arguably the finest exponents of their chosen branches of garden and botanical illustration. Gilbert White and his observations on weather at Selborne provide a commentary of crucial relevance to our own climate concerns.

The book also celebrates the pioneering women who became important in gardening and natural history. The garden-making of Mary, Duchess of Beaufort, at Badminton Park; Augusta, dowager Princess of Wales, at Kew; and Margaret, Duchess of Portland and her friend Mrs Delany at Bulstrode Park is examined in detail. The informal groupings this reveals, through family as well as shared scientific interests, are fascinating. (For example, the descendants of Henry Capel, the Duchess of Beaufort’s brother, sold Kew to Princess Augusta.) Also of great interest is the role of the aristocracy and the landed gentry as patrons of science. Society in the 18th century was closely knit and its members were aware, as the many quotes from correspondence demonstrate, of all its comings and goings.

Widowhood gave these energetic and industrious women opportunities to exercise their intellectual curiosity and artistic leanings. Feminine accomplishments such as watercolour painting and botanising were valued in Georgian society, practised at all levels, from Queen Charlotte and the bluestockings down to the smallest country-town gatherings. The crafts of decorative shellwork, grotto-making and the creation of feather mosaics helped to arouse scientific curiosity.

The duchesses of Beaufort and Portland had the means to entertain, and often employ, a circle of leading scientists and specialists. Mary Beaufort’s neighbour at her London home, Beaufort House in Chelsea, was Sir Hans Sloane, father of the British Museum. For three years, the Amsterdam botanical artist Everhardus Kickius lived at Badminton, the Beauforts’ Gloucestershire estate, where he made a magnificent Florilegium of the plants that the duchess grew there.

Chapter 6 examines the contribution of the Duchess of Portland at Bulstrode in Buckinghamshire and at her London house in Whitehall. Both were centres of a rich cultural life, drawing in celebrated figures of the day, such as Captain James Cook and the botanist and explorer Sir Joseph Banks. The naturalist Daniel Solander, a pupil of Carl Linnaeus, accompanied Banks on Cook’s expedition to the south Pacific, and instructed the duchess in the Linnaean system. Her chaplain and librarian at Bulstrode was the botanist Revd John Lightfoot, while her gardener John Agnew became an accomplished natural history illustrator. Mrs Delany, prime exemplar of Georgian accomplishments, spent the summers of her second widowhood making paper mosaics (in the British Museum since 1897) from flowers on the Bulstrode estate.

The final chapter is in the nature of a summary, looking ahead as well as backwards. William Curtis, demonstrator of botany at Chelsea Physic Garden in the 1770s and founder of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, forms a link between Bulstrode and the educated amateurs of the 19th century who, benefiting from the publishing revolution of their time, created a new democracy in gardening and natural history.

• Charlotte Gere is a writer, exhibition curator and 19th-century decorative arts specialist, who has published widely on jewellery, design and historic interiors

A Natural History of English Gardening, 1650-1800

Mark Laird

Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 440pp, £45/$75 (hb)