To celebrate its tenth anniversary, the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, which houses around 40% of Klee’s total output, has organised an exhibition exploring Klee’s relationship with the city where he was born and where he spent exactly half his life.

The show starts with early sketchbooks that reveal Klee’s extraordinarily precocious skills as a draughtsman. Pages are filled with carefully-observed drawings of his home and conventional nature studies completed on wanderings around the Bern countryside. School textbooks, their margins enlivened by doodles, demonstrate that Klee’s legendary playfulness had its origins in the scribblings of a bored schoolboy with a taste for the grotesque and satirical.

Unlike Klee’s later work, the early Bern pictures are largely monochromatic or muted in colour, but their themes prefigure those of his maturity. They are characterised by restless experimentation, an obsession with nature, creation and the cosmos, a fascination with the expressiveness of children’s art, humour, irony—and reflections on the role of the artist.

A revealing print, Comedian (1904), is actually a self-portrait of the artist hiding behind a mask. Klee stares out moodily from another self-portrait, a drawing from 1910, and his enormous, comical eyes appear in a hand puppet he created for his son Felix in 1922. The eye, which frequently stands for the artist himself, appears as a persistent motif throughout his career.

As a student, Klee made a five-part screen depicting the landscape around Bern’s river Aare, with a moody atmosphere that is a nod towards the Symbolist work he encountered during a spell studying under Franz von Stuck in Munich. But he regarded the 11 etchings of his Inventions series of 1903 as his first significant work. The attenuated forms of the works are also rooted in the style and pessimism of Symbolism, although they have a caricatural twist. The “reverse glass” works—drawings scratched into blackened glass panels—that he created around the same time are likewise infused with a sense of absurdity. In one, a lady with a capacious bosom towers over a tiny pet; in another a nude acrobat cavorts on a swing.

Klee’s first solo exhibition was held in Bern in 1910 and toured other Swiss cities without notable success. But by then he was living in Germany, becoming involved with artists of the Munich avant-garde, and his career was about to take off.

The show covers Klee’s better-known middle years with a representative selection of examples from his Der Blaue Reiter and Bauhaus periods, which illustrate his sheer versatility and joy for colour. This is not the show’s main focus, however, and for those who want to see more, there are some lovely mid-career works in the Zentrum’s About Trees exhibition. A trip to Bern’s Kunstmuseum also fleshes out the narrative of the German years, and places the artist in the company of his contemporaries like Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. A particular highlight is Klee’s Ad Parnassum (1932), which glows out from the walls of a first floor room. It was made shortly before Klee was labelled a degenerate artist by the Nazis, stripped of his teaching job at Dusseldorf Academy and forced into exile. The nervous lines of some hastily scribbled drawings displayed in the Zentrum exhibition testify to the horror of what he observed on the streets.

By 1933, Klee was back in Bern, where he spent the seven remaining years of his life. Although he was deprived of the daily friendship of his former colleagues and soon diagnosed with the painful skin condition that would ultimately kill him, his late years in Bern witnessed an astonishing creative outpouring that resulted in around 3,000 works, the majority of them drawings.

The paintings from this late period are more succinct and direct than before, with a raw surface finish. Klee’s canvases grew in size, and he covered them with simplified forms, ambiguous ciphers and symbols. Previously sensitive lines were replaced with deliberately crude dark outlines.

Perhaps as a reflection of his state of mind and health, many of the late paintings appear to be meditations on death and suffering. Insula dulcamara (1938)—roughly translated as “island of bitter-sweetness”—may reflect the dual reality of his life. Its subtle pinks and blues overlain with dark hieroglyphs suggest an underwater world populated by snakes and skeletons, while a mask-like face or skull is discernible in the centre. Angstausbruch III (1939) depicts a disjointed doll, evoking the disintegration of Klee’s own body. Paintings of angels with humorous imperfections of ugliness echo a preoccupation with the hereafter.

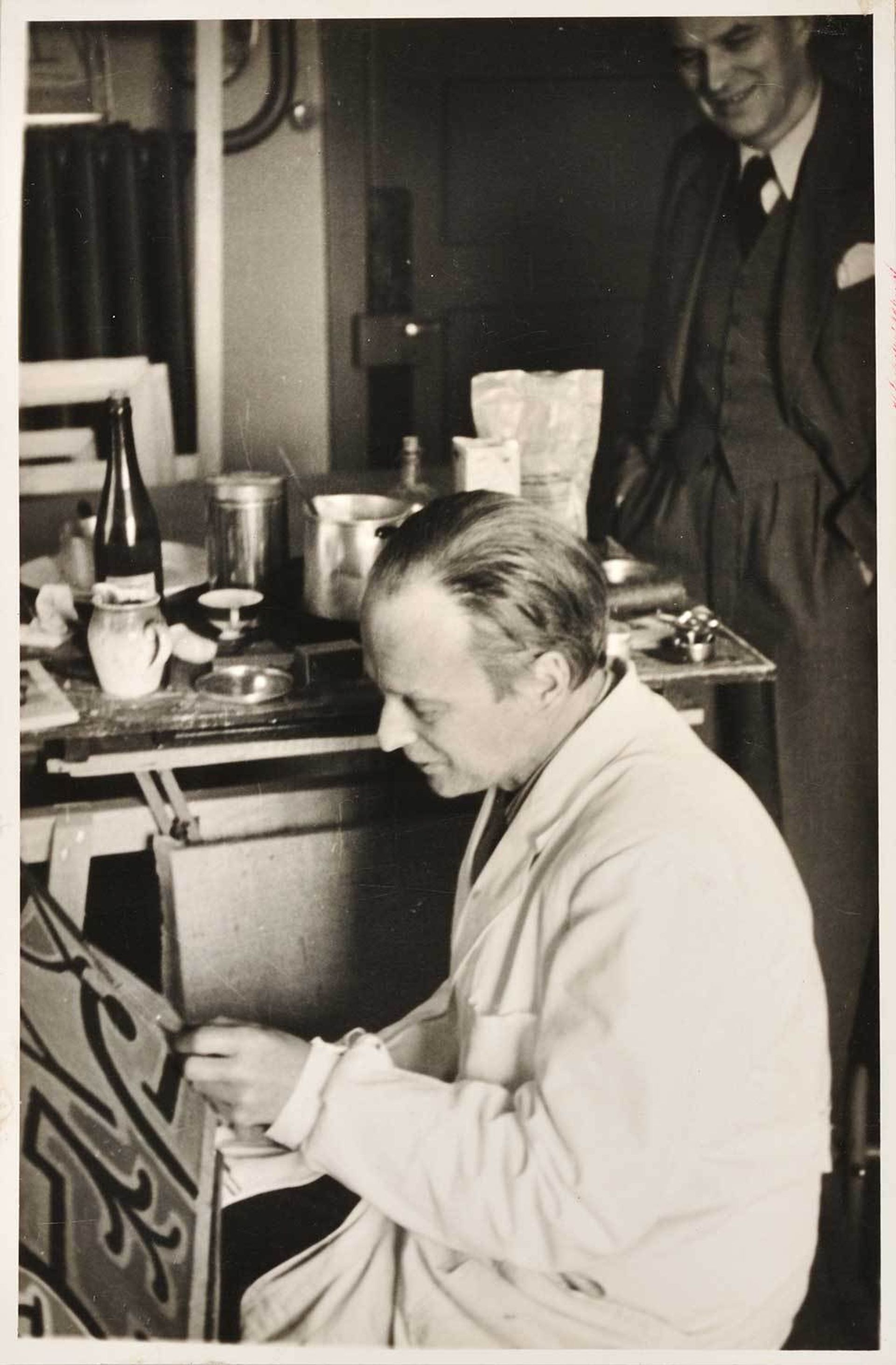

In the middle of one gallery is a reconstruction of Klee’s final studio room in Bern, its cramped dimensions a far cry from more luxurious working conditions at the Bauhaus. On the easel is an unfinished canvas he was working on when he died, a mass of squiggles that speak of undiminished energy. On the back, Klee scrawled “Should we know everything? I don’t think so.” It is precisely that unknowable quality that makes his works so tantalising.

Caroline Bugler is a freelance writer on art.

Paul Klee in Bern, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, until 12 January 2016

About Trees, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern until 24 January 2016