Forget the faces, look at the hands. The biggest surprise awaiting visitors to Goya: the Portraits at the National Gallery in London (the first such event ever staged anywhere) is just how mesmerically the Spanish Romantic renders hands—just how thoroughly his fingers steal the show. Though every work of visual art is an experiment in sign language, in Goya’s hands we find a silent symphony of gesture that competes with the mute music of his famously enigmatic eyes.

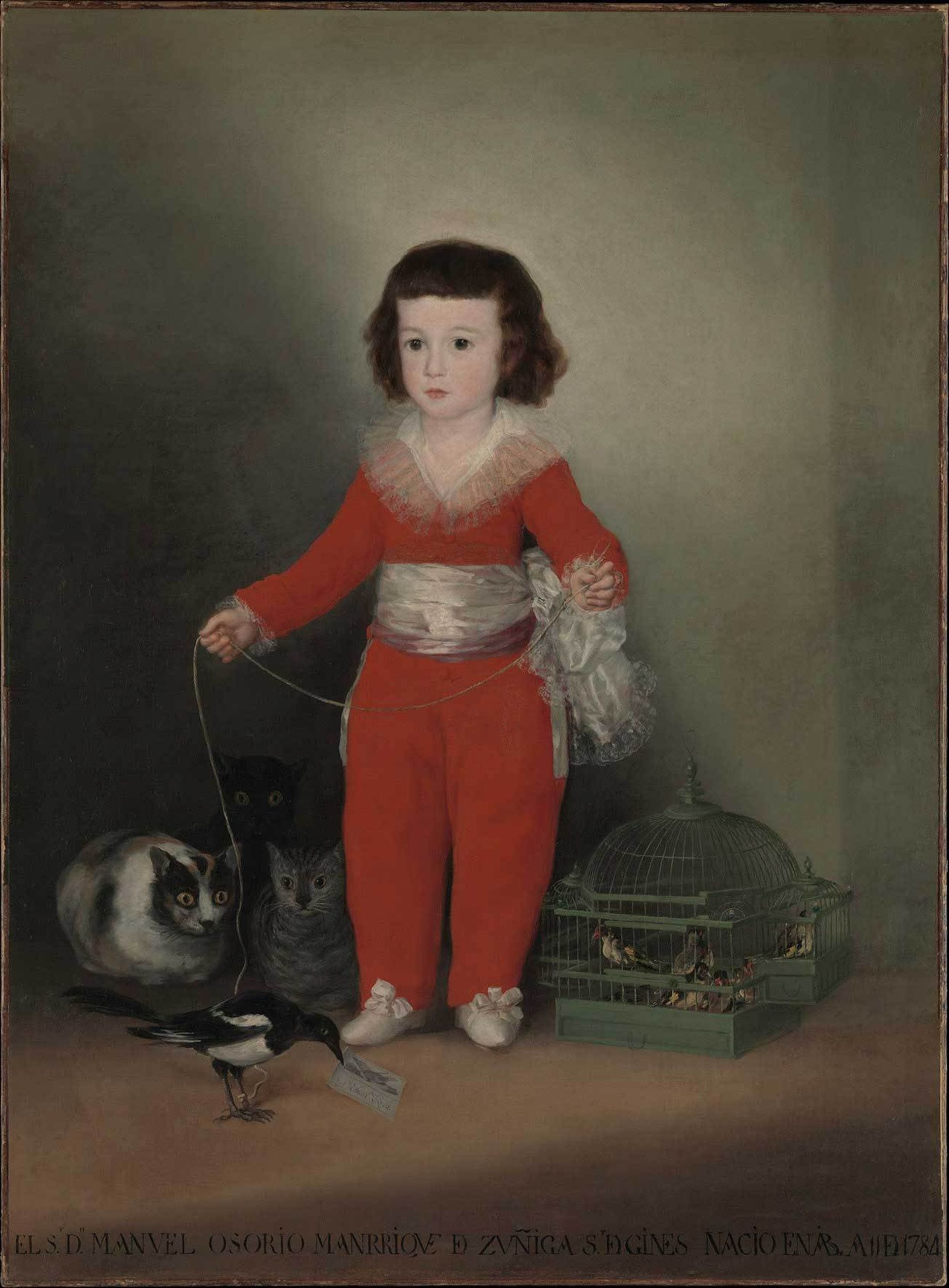

Goya’s show of hands across the seven rooms and 70 works that comprise this exhibition is unexpectedly magical: from a child’s loose grip on the cruel string that tethers the talons of his pet magpie (Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga, 1787-88), to the sweaty squeeze of a tyrant on his phallic ceremonial scepter (Portrait of Ferdinand VII, 1814); from the tender, self-conscious fold of an actress’s hands on her lap (Portrait of Doña Antonia Zárate, around 1805-1806), to the effortless pinch of the artist’s own fingers on a paintbrush that floats like a wand in a self-portrait (Self Portrait before an Easel, 1792-95).

Goya’s command of the hand is apparent from the very first major commission on display: his 1783 depiction of The Count of Floridablanca, the second most powerful man in Spain. Though the portrait is often derided for the allegedly vacant, porcelain stare of Goya’s distinguished subject (whose garish silken attire floods the centre of the canvas with outrageous red), there is real drama in the hands of the painting’s players. Behind the central figure, the fist of the Count’s military engineer, Julián Sánchez Bort, crouches on a table like a pinless grenade, his fingers clenched tight around a draughtsman’s compass. The compass’s spin has been interrupted by the sudden entrance into the room of Goya himself, whom we see in shadowy profile to the left, his own hands gripping the sides of the very portrait at which we’re staring, establishing a meta-narrative of painting-within-painting that he pinched from Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656). But what masterfully brings together Goya’s composition is the right hand of the Count himself, which cradles a dainty pair of gold-rimmed spectacles. By gently extending an imperious index finger to the artist’s face, the Count suspends the forward momentum of the impatient young portraitist, eager to show his work. Like a conductor holding back the blare of an orchestra with a slender baton, the Count’s permanently poised finger creates the perpetual instant and space from which he will stare out at us eternally.

Those familiar with the dark visions for which Goya is best known (from his attacks on a superstitious society in the macabre prints of the Los Caprichos series from the late 1790s, to the disturbing scenes of his Disasters of War works from the 1810s, to the terrifying “black paintings” he made late in life), will hardly regard as revelatory the artist’s ability to choreograph mannerisms. After all, are there any more dramatic hands in 19th-century Western art than those outstretched messianically in Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814), or those that crush the spine in his nightmarish Saturn Devouring His Son (1819-23)? But what’s truly arresting in the pantomime of gesticulation that quietly unfolds in the National Gallery is how Goya turns ephemeral physiques and fleeting body language into an eloquent grammar of endlessly audible signs.

Goya’s obsession with the quiet parlance of palms and the natter of knuckles intensified after 1793, following a mysterious illness that left the artist completely deaf. Until his death in 1828, Goya was left to rely entirely for conversation on what hands are capable of conveying to the eye. “For the last six years I have been greatly indisposed”, the artist confessed in a letter to King Charles IV of Spain in March 1798, “especially having lost my hearing to the extent that I am unable to understand anything without the use of sign language.” That heightened awareness of the volubility of gesture after 1793 is everywhere conspicuous in the works on display in the second half of the exhibition.

The power of his famous portrait of the widowed Duchess of Alba (on loan for the first time from the Hispanic Society of America) relies as much on what her hands exclaim as what her eyes inscrutably conceal. The nature of the relationship between Goya and the Duchess—a fiery-tempered beauty whose “every hair”, a French traveller once wrote, “inspired desire”—has long ignited intrigue among historians. Central to the fascination over whether the two were ever physically intimate is the drama that drips from the fingertip pointing downward towards the sand at her feet, where the two words “Solo Goya” (“Only Goya”) were excavated beneath layers of paint and varnish by 20th century conservators. Not since the alleged encryption of hand-signals in Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks (1483-86), in which the unfolding fists of Madonna and the infant Christ were said to spell out the artist’s initials, have the gestures of a painting’s subject been so egotistically ventriloquized.

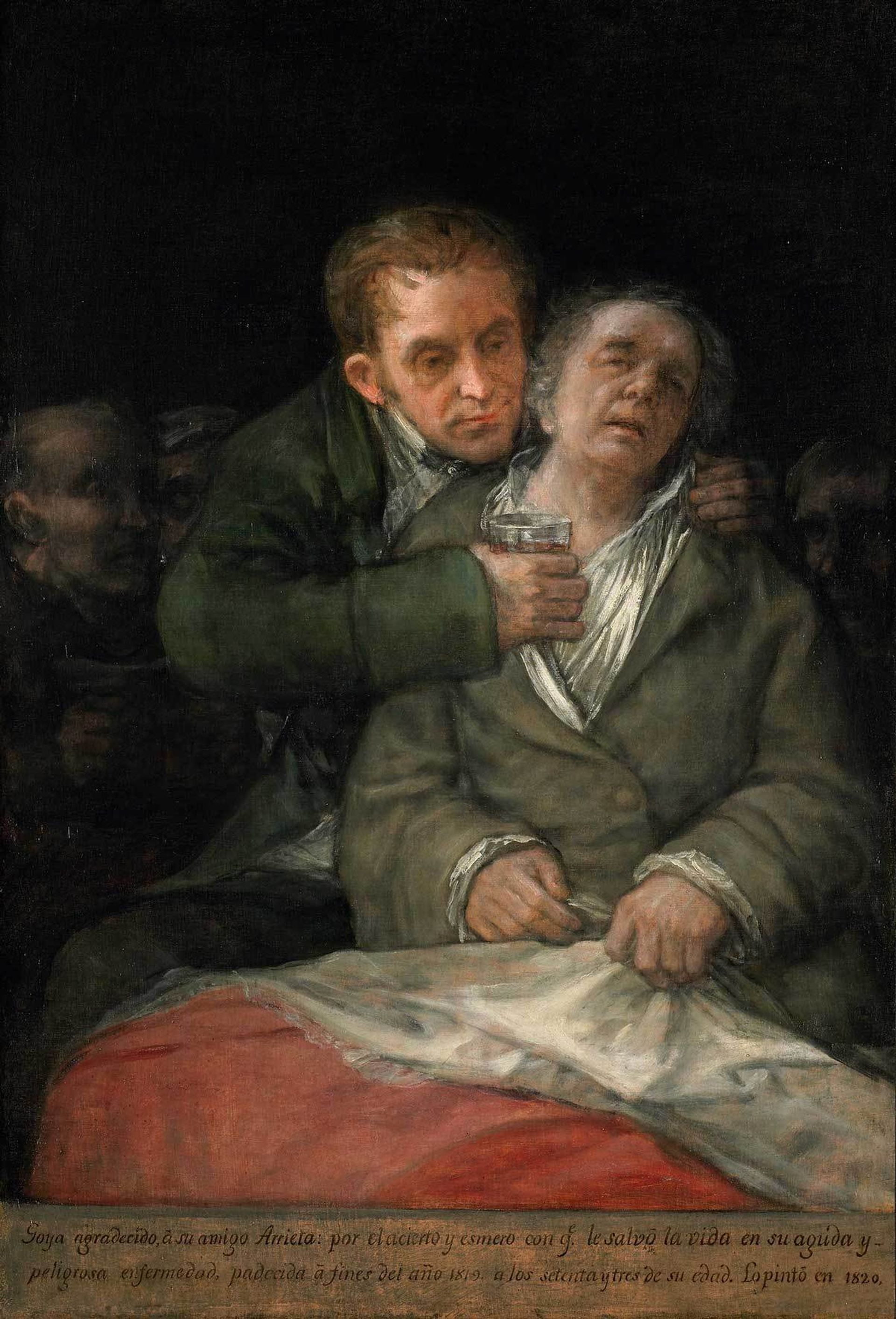

Even when Goya’s brushstroke began to loosen in old age, his ability to pluck a tight harmony from the music of fingers never weakened. Among the last works on display is perhaps the show’s most moving: Self-Portrait With Dr Arrieta (1820), which depicts the ailing artist in the compassionate embrace of his friend and physician Dr Eugenio Garcia Arrieta. The tension between the tender tentativeness with which Dr Arrieta offers his patient medicinal elixir and Goya’s own dwindling grasp of the bedsheets draped across his lap is as sculptural as Michelangelo’s Pieta (1498-99). The humanity that pulses through the veins of Goya’s portrayal—now clenching life, now death—is heartbreaking in its poignancy. Though I entered the exhibition intent on tracing the psychologies of Goya’s faces, this extraordinary show left me eating out of his hands.

Kelly Grovier is a poet and art critic. His new survey, Art Since 1989, will be published thsis month as part of Thames & Hudson's World of Art series.

Goya: The Portraits, National Gallery, London, until 10 January