Rashid Johnson is not “post-black.” The term, which has been used to describe his work since his participation in the exhibition Freestyle at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001, was coined by the museum’s then-chief curator Thelma Golden (she is now the director) to refer to those who reject labels like “black artist”—“though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of blackness,” she wrote in the exhibition’s catalog. When Claire Gilman, a senior curator at the Drawing Center in New York, used the term to introduce Johnson to a small crowd gathered for a walk-through of his current solo show, Anxious Men, the artist offered a humorous pushback: “I’m currently black,” he said with a laugh. It was meant for comic relief, but it struck at the seriousness of the exhibition.

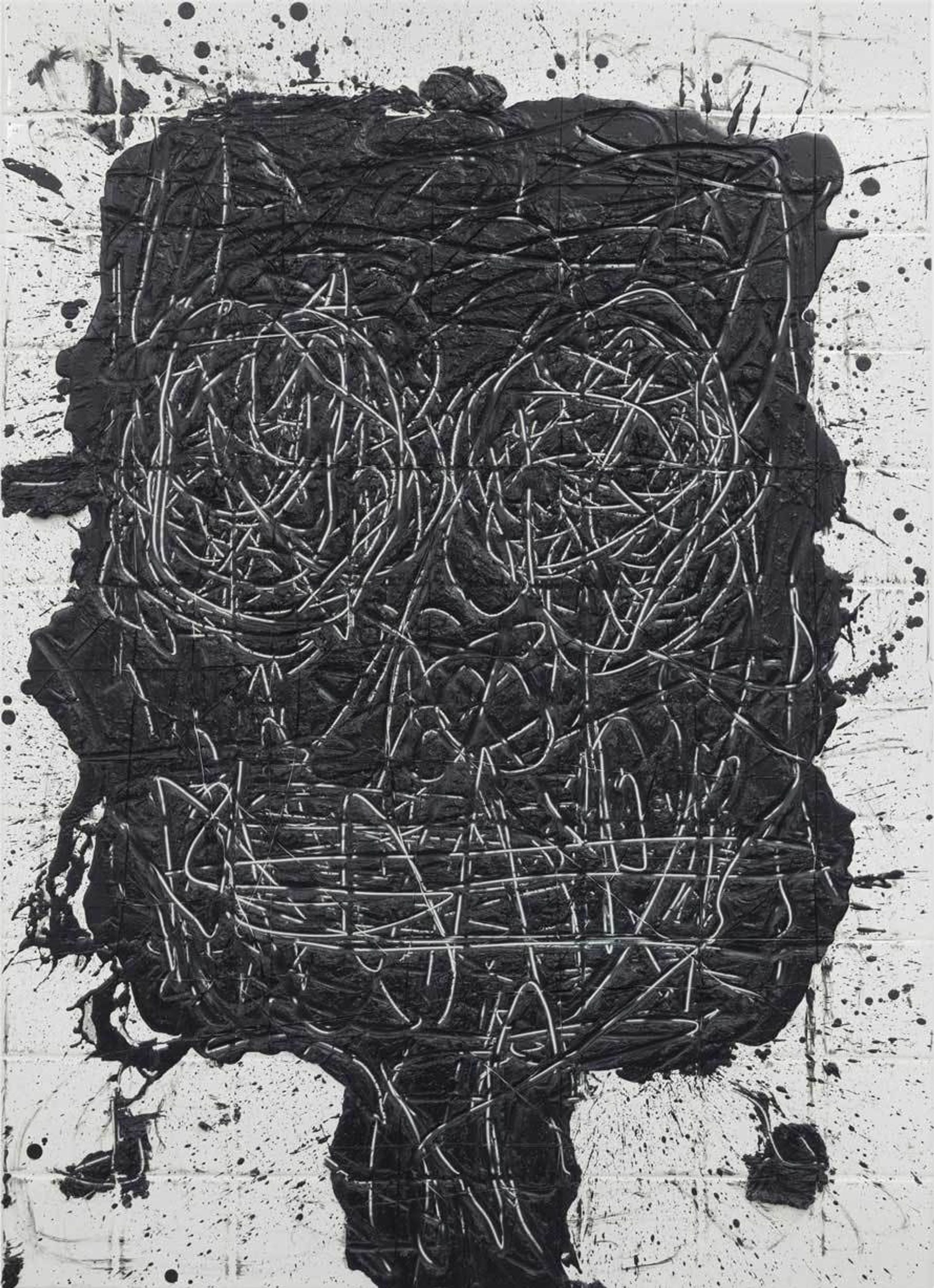

Anxious Men is Johnson’s attempt to grapple with “negrosis,” a phrase he uses to describe the relationship between blackness and anxiety. The show, which includes a group of portraits drawn onto white tile with black wax soap, is a clear meditation on the social circumstances many black men face daily, such as the possibility of police brutality. It is also, Johnson explained during the walk-through, his attempt to communicate these circumstances to his young son.

Though Johnson’s approach to figuration is quite abstract, it is not difficult to detect melancholy. The expressions of the depicted men are overwhelmingly sombre. There is little variation in the work except in size. The works are mounted onto walls covered in wallpaper with a repeating photograph of Johnson’s father. In the photo, his dad sits cross-legged in a taekwondo uniform. On the bookshelf in the background, there is a copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Johnson’s father wears the expression of a man concerned about parenthood or perhaps, more specifically, about his own ability to be a black father to a black son in this world: negrosis. Johnson’s use of repetition in the photograph and in the drawings implies that this is an unavoidable anxiety.

The exhibition is framed by the soundtrack to the 1977 comedy film Watermelon Man, directed by Melvin Van Peebles. In the film, a white insurance salesman wakes up one morning to find that he has become black. His identity crisis—navigating the world as a perceived threat, as a black man—emphasises the truth of Johnson’s work: that to be “currently black” is a fraught lived experience.

Yet Johnson is never didactic. Aside from the score and wallpaper, there are no other allusions to race. There are no explicit markers that refer to black American life, nor pointed messages condemning or acknowledging acts of police brutality. And still a mood of introspection looms over his portraits and we are made to contend with an artist who refuses to divorce himself from the social realities of this world.

Those familiar with his work—which often takes the form of mixed-media sculptures and installations—might be surprised that the Drawing Center is home to this exhibition. It is the first time Johnson has exhibited drawings. Still, his signature approach to materials is recognisable. Black wax soap is consistently part of his work. Together, the sound, drawings and wallpaper create an environment that is at once intimate and sobering.

As I walked through the gallery, I was confronted by my own negotiations with identity. Do I too suffer from negrosis? Is there a remedy for this diagnosis? Zora Neale Hurston once wrote that she did not weep at the world because “I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.” Each day, I wake with the intention of sharpening my own oyster knife, and some days I fail at that task. How can I assume post-blackness if the world sees me as nothing but? Like Johnson, I have not yet transcended the material consequences of my blackness, of which anxiety is part.

Yet the cultural specificity of Johnson’s preoccupations does not impede a universal reach. Indeed, it is as if Johnson is asking us all: Where does your anxiety live?

Jessica Lynne is a writer, arts administrator and co-editor of the online journal, Arts.Black

Rashid Johnson: Anxious Men, The Drawing Center, New York, until 20 December