Lee Miller: a Woman’s War, Imperial War Museum, London (until 24 April 2016)

It is now common knowledge that Man Ray’s stunningly beautiful assistant, model and muse was also an accomplished photographer in her own right. Lee Miller shared the credit for rediscovering Man Ray’s trademark solarisation process, and her ability to fuse the conventional with the experimental, made a key contribution both to fashion photography and the Surrealist movement. Yet less attention has been paid to the exceptional photographs taken by Miller around the Second World War, which here are at last given proper attention.

We see her subjects shifting from playful Surrealist high jinks to the ways in which women’s lives were transformed in wartime Britain. Then, as one of only four female correspondents accredited to the US army, we see how Miller’s images for British and American Vogue went on to highlight women’s experience across Europe before, during and after the Second World War. With insight, empathy and often a wry humour, she showed women from all walks of life, whether as civilians or in uniform, immersed in active service as well as post-war liberation, defeat and military occupation. Among these images are a shaven-headed woman accused of German collaboration; an exhausted nurse attached to a Normandy evacuation hospital; a female inmate-doctor in Dachau concentration camp; a group of women cooking fish on an outdoor stove amidst the ruins of Nuremberg; and a defiantly chic Parisian resistance worker. Crucially, Miller did not shrink away from showing the emotional and physical toll of war and its aftermath. The legacy affected her profoundly and she descended into alcoholism and depression in the postwar years up to her death in 1977. It is telling that the exhibition’s last image of Lee Miller shows the intrepid war correspondent in her Sussex kitchen preparing a summer pudding.

James Capper: Prototypes, CGP London The Gallery and Dilston Grove (until 6 December)

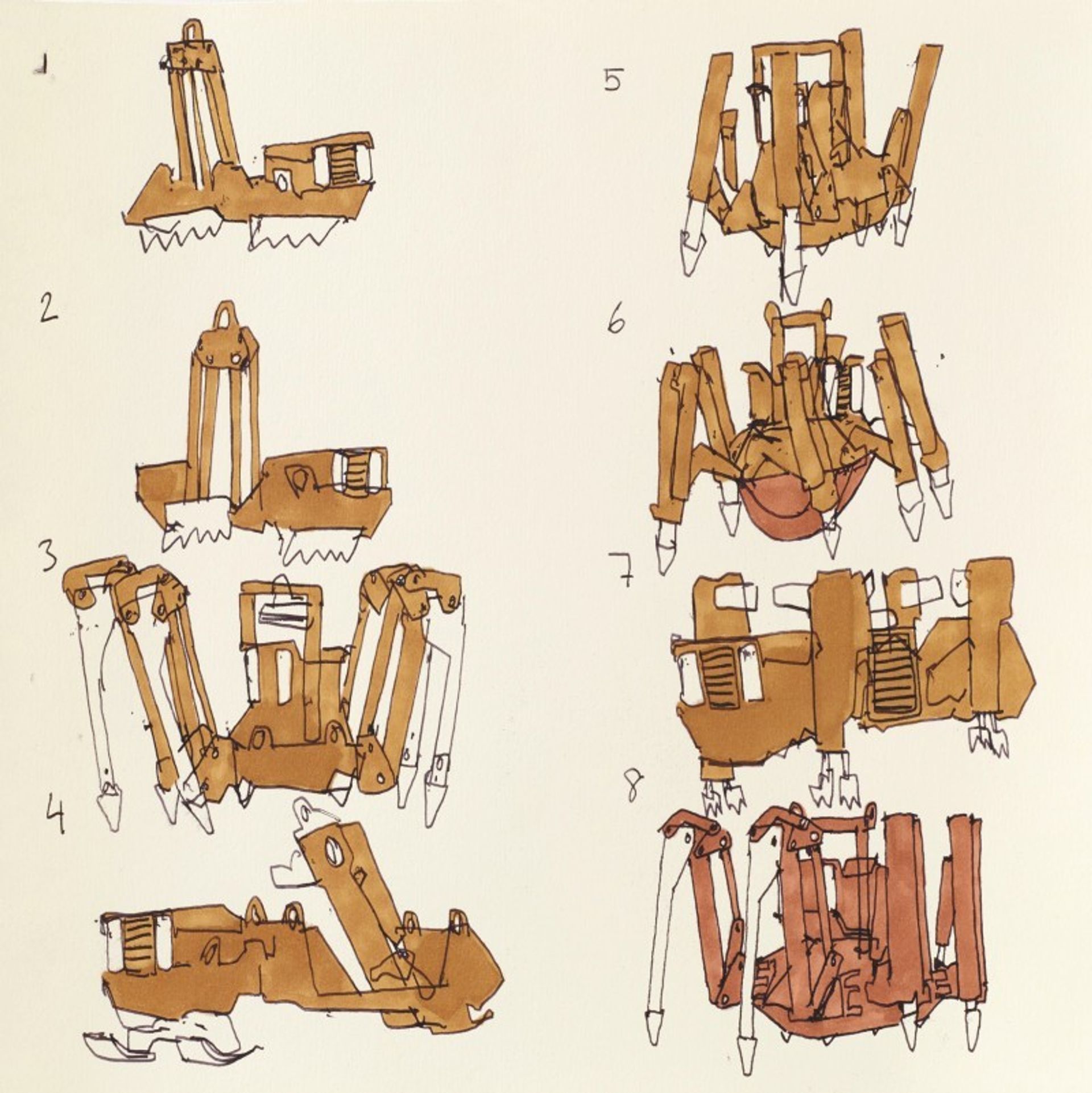

Baring their various jaw-like blades as they crouch on low plaster blocks, the anthropomorphic sculptural machines of James Capper are dotted throughout the austere interior of this deconsecrated church like a bizarre congregation. Just in front of where the altar would have been, is the giant Atlas Prototype, which, in an oblique homage to being housed within the first poured-concrete church in Britain, has been specially designed to carve its cubed, concrete plinth into a sphere. You expect this to happen with a deafening din, but the Atlas performs this task with an almost forensic delicacy belied by its industrial appearance and the power of its rotating ball gouger.

As is confirmed by the accompanying show of drawings, maquettes and other earlier works at The Gallery—and contrary to first impressions—Capper’s machines are not customized pieces of existing heavy machinery. Instead, they are highly considered inventions that have been meticulously researched and built from scratch by the 28-year-old artist. In this, Capper’s largest show to date, we see that his strange beasts are more about creative transformation than violent destruction.

Giacometti: Pure Presence, National Portrait Gallery (until 10 January 2016)

Alberto Giacometti may have declared, two years before his death, that “it is impossible to paint a portrait”. But this first ever exhibition devoted to his portraiture shows that a desire to “catch an appearance” was a lifelong preoccupation and underpinned everything he did. Despite claiming in 1925 to have abandoned observation—and however abstracted his famous, knobbly, elongated figures of walking men and standing women were—throughout a career spanning more than half a century, Giacometti never ceased to grapple with portraiture. In the show we see many examples of this, from a precocious head of his brother Diego modelled from a ball of plasticine, made when he was 13, right up to the last bronzes of Eli Lotar and the paintings of his final female model, Caroline—all made in 1965, the year before his death.

Separate rooms devoted to each of the artist’s individual long term sitters—his mother and father, brother Diego, wife Annette, and the young woman he called Caroline— provide a fascinating opportunity in which to chart the evolution of Giacometti’s unique artistic language, as well as to be made party to his intense engagement with this cast of characters. Simultaneously intimate and grand, this important exhibition takes us to the raw core of both artist and sitter. And it shows how emotions, passions and a rich range of human relationships lay at the heart of his supposedly existential vision.

Fiona Banner: Scroll Down and Keep Scrolling, Ikon, Birmingham (until 17 January 2016)

THE BASTARD WORD glares large, written in wonky neon that runs across an entire wall of Fiona Banner’s excellent Ikon exhibition. The show spans 25 years of work in which words—in all forms, fonts, shapes and sizes—have played a central, if slippery part. Letters, text and punctuation proliferate in an exhibition whose very title is Scroll Down and Keep Scrolling (written in a specially invented font that amalgamates all the typefaces she has ever used) and which opens with a stone Victorian font, engraved with the word “Font”. There are ceiling-high towers of books, books as benches, and a wall-sized “wordscape” that papers another wall with a lurid pink, upside-down transcript of a porn film, which is almost impossible to read.

War intertwines with words, as another much-mined theme: whether it be a film of a Chinook helicopter, performing aerobatics or in Banner’s THE NAM (1997). The latter is a brick of a book—containing densely-written, frame by frame, accounts of Vietnam movies—that is piled up in a disorientating room lined with NAM publicity posters, which constantly flicker and change colour under a bombardment of dazzling lights. Then there is Banner’s recent collaboration with a Magnum photographer to take pictures of London’s financial district as if it was a war zone uniformed and scarred by pinstripe, and filtered through Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. It may cover a swathe of time, but there is nothing ploddingly chronological about this dynamic show in which works old and new—and sometimes never before seen—have been revived, rebooted and made to keep new company and strike up new relationships.