Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed. This is Unesco’s guiding principle, set down in 1945. Seventy years after its foundation, the so-called intellectual arm of the United Nations and its director-general Irina Bokova are in a deep crisis, fuelled by steep funding cuts—principally inflicted when the US withdrew its funding in 2011 after a vote to grant Palestine full Unesco membership—as well as entrenched structural problems and growing threats to cultural heritage across the world.

With 195 members, Unesco (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation)now has little in common with the idealistic club of 30 countries that first met in Paris in late 1946 and elected the British biologist Julian Huxley as its first director-general. Today’s Unesco is much more complex, with a huge mandate that is vulnerable to the political priorities of its members.

“Irina Bokova did try to manage her way through a very difficult situation,” says Francesco Bandarin, who, until 2014, was her assistant director-general for culture. “The truth is, Unesco is hit by not one but two severe conflicts: how can its humanist message be implemented if the budget collapses? And does the idealist vision born after the Second World War still work in today’s world?”

In October, Bokova declared that Unesco’s mandate “has never been more relevant” than today when “the forces of fragmentation, hatred and violence are there for all to see”. She added: “We see the unprecedented rise of violent extremism, accompanied by cultural cleansing. We see cultural heritage destroyed, looted. We see communities persecuted. We see education under attack, and children, girls especially, abused, forced out of learning. We see women violated as targets of warfare. We see freedom of expression challenged, journalists beheaded.”

Golden age In the past at least, Unesco had a big impact. In 1945, its top priority was education and it played a key role in huge national campaigns against illiteracy. In 1929, an international study by the US Bureau of Education concluded that 62% of the global population aged ten years and over could not read or count. Although the situation remains dire in countries with an enduring gender gap such as Mali and Afghanistan, literacy and education rates have soared in Latin America, the Arab nations and, more recently, Asia. Through its highly regarded Institute for Statistics, Unesco pushed to establish and analyse relevant data, so that policymakers knew exactly how their countries were faring and where there were gaps. Its Global Monitoring Report has become the document of reference on the state of education worldwide.

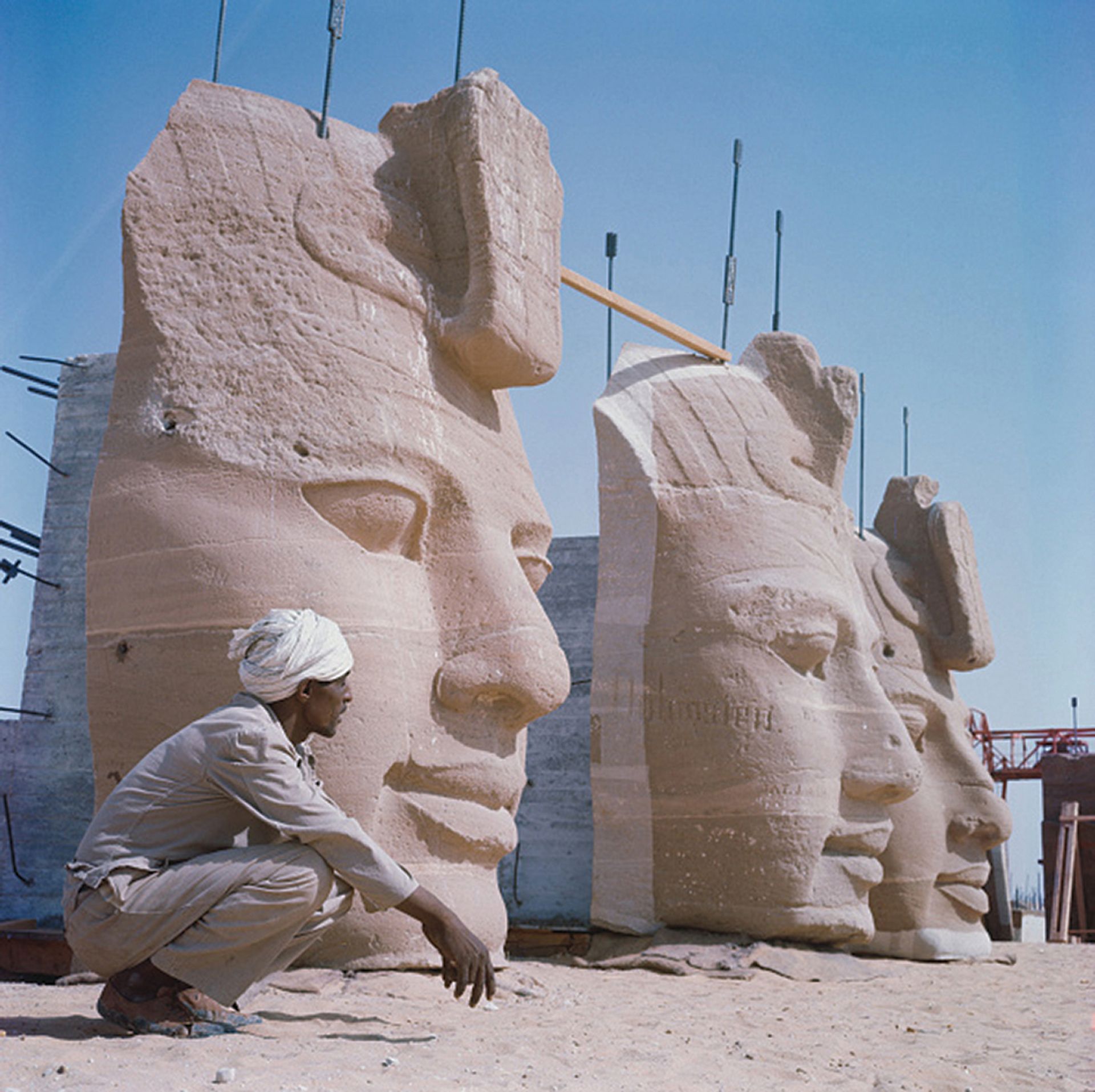

“Unesco took much longer to understand that culture was also a top issue,” Bandarin says. In the early 1960s, its international campaign to save the Nubian temples in Egypt from being flooded by the Aswan High Dam was the first recognition of the universal value of cultural heritage, leading to the global conventions of the 1970s. The list of the world’s most valuable cultural and natural sites and the convention against illicit trafficking of cultural property became Unesco flagships.

Its influence also led to other groundbreaking developments. To protect the work of artists and creators, Unesco established the copyright convention and, indeed, the © symbol. It wrote the Florence Agreement in 1950 to abolish income tax and custom duties on educational, scientific and cultural publications.

Unesco also introduced the word “ecology” into politics. In 1968, it held an international conference to reconcile development with environmental conservation, leading to the concept of “sustainable development” that emerged in the 1980s. Its promotion of international networks to monitor the health of the oceans led to the discovery of a 30% rise in ocean acidity since the Industrial Revolution. It also launched what has now become virtually a global warning system for tsunamis.

But this golden age now appears over. Bokova is fighting hard. Within the UN itself, she wrested back the leadership on education from Unicef. She is also determined to maintain Unesco’s role in environmental science and its reputation as the only international body defending press freedom, discussing internet governance and fighting against doping in sport. Last spring, she notched up a major success with a UN Security Council resolution against the destruction and looting of cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq.

Her protests against Isil’s attacks on museums and temples may seem symbolic, but Mounir Bouchenaki, the director of the Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage in Bahrain, thinks otherwise. From 2000 to 2006, the Algerian archaeologist was in charge of culture at Unesco. “In Mosul [Iraq], as in Baghdad or Kabul before,” he says, “most of the museums’ collections were put into safe-keeping before the looting and destruction. In Timbuktu, the sacred manuscripts are being restored and mausoleums reconstructed… but such an action can be taken only when minimal security is met: Unesco has no armoured division.”

At the UN General Assembly in September, the Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi called for a task force of “blue helmets” to protect cultural heritage, under Unesco leadership. To apply the UN Security Council resolution concerning cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq, Unesco is co-ordinating with Interpol to counter the trafficking of Mesopotamian artefacts. For the first time, a suspect was brought to the International Criminal Court in the Hague in September, for the destruction of cultural heritage in northern Mali.

In the meantime, Bokova herself insists on “the responsibility of the member states to give Unesco the means it needs to face today’s major challenges”. But while the member states may well represent a large part of the solution, they are also perhaps Unesco’s biggest problem, increasingly holding the organisation hostage to political interests and nationalistic pressures.

The last executive board meeting in October was shaken by controversy over sites in Jerusalem at the centre of Israeli-Palestinian disputes: Unesco condemned Israel for restricting the freedom of worship at the Al-Aqsa mosque, but dropped a clause in the resolution claiming the Western Wall as a space reserved for Muslim people. Unesco also reaffirmed that biblical tomb sites in Hebron and Bethlehem were “part of Palestine”. Meanwhile, Kosovo’s request to be recognised as a member of Unesco prompted Serbia’s foreign minister Ivica Dacic to say that it would be as absurd as admitting Isil to the organisation.

Credibility undermined Such concerns should not have to be priorities. “It has become the theatre of all political conflicts by proxy,” says one diplomatic source regretfully. Meanwhile, the Memory of the World Register, which lists invaluable documentary heritage, is caught up in a conflict between China and Japan on archives relating to the 1937 massacre in Nanking (now Nanjing) and sex slavery organised by the Japanese army during the Second World War.

Even the cultural heritage programmes, the jewels in Unesco’s crown, are at risk of being derailed. What started out as a record of sites of “outstanding universal value” has fallen victim to nationalistic and economic interests, with the World Heritage label mainly used to lure tourist dollars. Experts are concerned by the “inflation” of its list, which now includes over 1,000 sites, and the growing tendency of diplomats on the World Heritage Committee to dismiss their recommendations. France, for example, has lobbied hard for the admission of its vineyards and extinct volcanoes. The “gastronomic meal of the French” now enjoys the status of an Intangible Cultural Heritage treasure. The credibility of this list, which some saw as the most innovative step taken by Unesco for a long time, is now undermined by requests for the inclusion of such cultural landmarks as the making of Neapolitan pizza and Korean fermented cabbage.

No field seems safe from blatant political interference. A prize for life sciences research “that improves the quality of human life” is funded by Equatorial Guinea, with the support of all African representatives, despite an outcry from human rights organisations pointing out that the country is one of the bloodiest dictatorships in Africa. In Venice, in November 2011, a scientific conference on “the future of the city and the lagoon in the context of global change” was cancelled at the last minute under pressure from the Berlusconi government, which feared criticism of the MOSE (or Moses) flood barrier project, into which it was pouring €5.4bn. Thirty-five people, including Venice’s mayor, are now charged with having taken bribes from a €25m kickback fund set up by the consortium in charge of the project.

Specialists working for Unesco say they have their work cut out to avoid political squabbling while collaborating with experts on the ground. The Chilean marine biologist Patricio Bernal, who headed Unesco’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) until 2009, praises the work done on hydrology and geology, but also points to “missed opportunities”. He says the IOC “is too much on a political track now, introducing a huge risk to work being done to assess the health of the oceans”. He regrets Unesco’s inability to launch a “global scientific forum that could deliver the basic facts on environment and nature for all countries”.

When Bouchenaki talks about sensitive issues such as archaeological digs in Jerusalem or damaged Byzantine mosaics in Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, he insists that Unesco’s mission is “not political, only technical”. But mindful of potential political interference, he has taken the precaution of systematically setting up a multinational scientific committee. “Many countries treat Unesco with utter contempt,” says a keen observer of the organisation, comparing its Paris HQ on the Place de Fontenoy, where permanent delegations have their offices, to a “cesspool”, with representatives plotting and promoting their own interests while subjecting the accounts and actions of Unesco’s secretariat to tight scrutiny. People accused of embezzlement and even arms trafficking have been part of this exclusive group at various times, shielded from legal action by their diplomatic status.