On the occasion of Ai Weiwei’s exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, his former teacher, Sean Scully, reflects on his relationship with the artist. Another version of this article appears in the catalogue for the exhibition.

In 1983 I was teaching at Parsons School of Design in Manhattan. Every year there were two professors, and I was one of them. The class, which always had 26 students, was always divided in half. That year, nine of the 26 were from the East, many from China. I got them all, on account of my patience. So I had nine from Asia and four from New York, and the other professor, who had a paucity of tolerance for people who speak slowly and think in four dimensions, had 13 Americans. That seemed fair and just. Most of my American students were free to engage in a self-referential festival of local in-jokes and vernacular, while I laboured with the strange ones. I didn’t mind, though. I found it, on occasion, hypnotic and deeply tender.

One of my strange ones was Ai Weiwei. He was a young, modestly immodest man. At the outset, the students all had to make a painting and they were in awe of the perfectly terminal perfection made by Weiwei. They waited and expected me to praise it and join them in awe. But being in love with growth, I said that its smugly realized completion was its death, thus making it paradoxically the worst painting I had ever seen. The ranking order in my class was cataclysmically reversed. Ai Weiwei was a man who had just stepped into an elevator whose cable had snapped, from the penthouse floor, only to arrive, physically unharmed, in the basement of the same building.

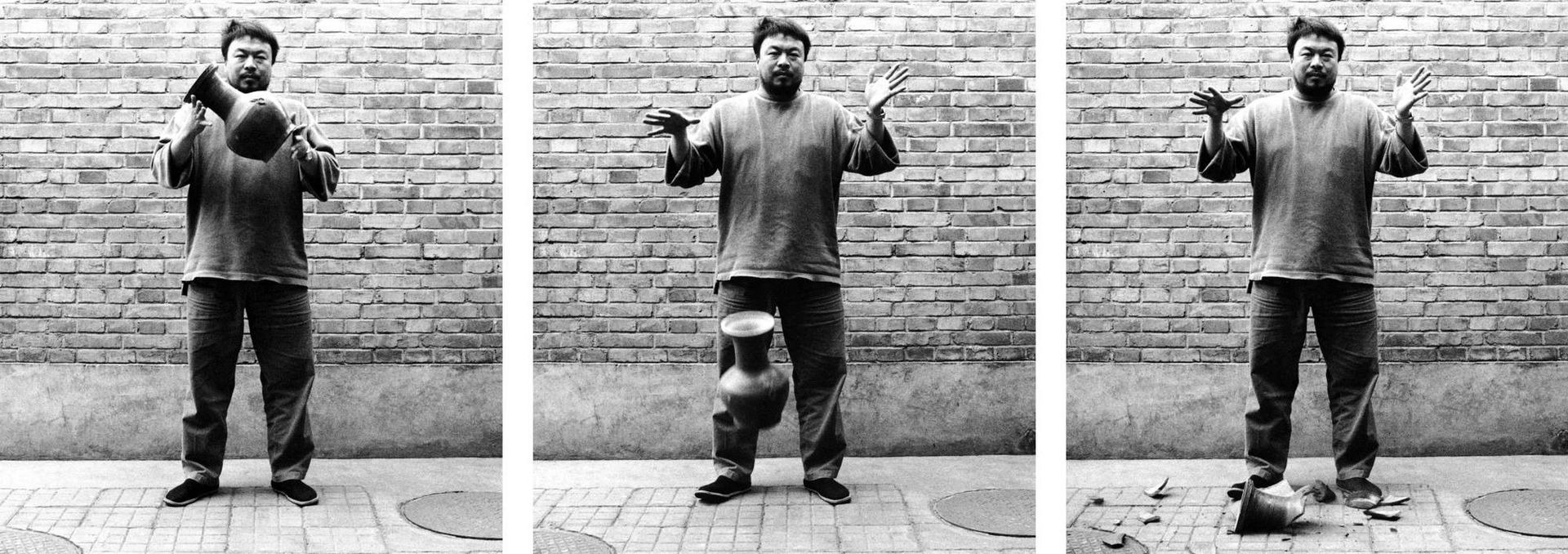

His brutality was very beautiful. Instead of arguing with me in English, in which he could never prevail, he simply threw away his paint. I should have used them myself, but I didn’t think of it. Together, we made an agreement to study the history of the “other” wing of art: Conceptualism. I don’t practice it literally. I am too deeply attached to the pre-verbal profundity that painting believes it can incarnate.

Metaphorically speaking, Weiwei would arrive every week with his initially empty bucket and I would put a parcel of information in. From Andre Breton to Marcel Duchamp to Meret Oppenheim to the kick in the pants people felt as they left Kurt Schwitters’s studio. Then, on to the philosophical poetry of Joseph Beuys, the Germania of Hans Hacke, earth works and Walter De Maria’s Broken Kilometer and its parent, Piero Manzoni’s Linea Lunga. Then video: getting yourself shot or nailed to a Volkswagen with Chris Burden. Then up to my best friend Peter Nadin, who used to do construction work and then sign it.

When Weiwei’s bucket was full, we both understood that my usefulness to him and his fascination with me had arrived at their destinations. His head, now inhabited by Western thoughts of ego, assertion and fame, tilted slightly in my direction, as we bid each other farewell. I imagined that he would do as many of my other Chinese students had done, and insinuate himself into the tightly woven fabric of Chinese society. But then he became famous and was adored in Europe.

Thirty years later, I arrived at his beautiful blue door outside Beijing. On the way, my driver got lost. I was taking photos with my iPhone. I found myself taking a picture of a house, which happened to have a young woman at the window, taking a photo of me taking a photo of her. She was laughing and so I joined in. Eventually, after a little adventure in the hinterland of Beijing, Weiwei and I embraced, closing the 30 year space that had grown between us.

We entered his room and he told me why carpenters didn’t like to work with pine. Then we went into his studio, which is, strangely, exactly the same size as mine in Germany (10 by 20 metres). We both agreed it was a human scale, big but not enormous. I saw a big photograph of his that reached out and put its hand on my heart. I wanted it. I still do. It is a tree made of trees that are not the same, as if the longing for union is overthrown by the assertion of difference.

He said, miraculously, that it came from my teaching ideas. My metaphor was the city. Things want to be together to complete our possible wholeness, and they are alike, but they are not the same. What is similar is also not. His metaphor is the tree. Like people, all trees want to be together (though we know that the birch, if it is able, will kill the oak). Our wholeness is at the end of our long road, and we are perpetual road builders.

Sean Scully is an artist.

Ai Weiwei, Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 13 December