Goya: the Portraits, National Gallery (until 10 January 2016)

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes may now be known as the painter of searing satire and dark, nightmarish imaginings, but during his lifetime he was known as a painter of exceptional portraits, which make up a third of his oeuvre. This captivating exhibition—astonishingly the first to be devoted exclusively to his portraiture—confirms that the unsparing brilliance with which Goya scrutinized the world around him in Los Caprichos or The Disasters of War, also enabled him to emerge as the greatest portrait painter of his day. While his gaze was unstintingly objective and could present his sitters in a decidedly unflattering light, such was his skill that Goya survived one of the most turbulent periods in Spanish history. During his time he painted kings, queens, courtiers, politicians, generals as well as, more informally, his fellow artists, his friends and—most revealingly—himself.

We see that Goya turned official portraiture upside down by making it about the person who inhabits the role, rather than the role itself. He could get to the essence of a sitter on a single meeting: his drawing of a hollow-eyed, war-torn Duke of Wellington presents a very different view of the so-called Iron Duke. Even in his more awkward early portrayals as well as his grandest formal commissions, Goya showed an uncanny ability to depict his sitters as real people and to reveal their inner lives, as well as their outward appearance. No wonder the Goya expert and Prado curator Manuela Mena Marqués considers that his ability to penetrate the human subconscious looked ahead to Freud. But “in this case Sigmund, not Lucian.”

Jimmie Durham: Various Items and Complaints, Serpentine Gallery (until 8 November)

Artist, poet, performer, essayist, political activist—the many modes of Jimmie Durham are worn lightly but trenchantly in this survey of work dating back to the 1970s. One of the most haunting exhibits is a film made this year of Durham singing a medley of half-remembered songs from his childhood, which he describes as “a bad echo of a childhood in Arkansas, the most racist state in America.” All aspects of western society are given a wry and sly trouncing: Christianity, democracy, oil and the art world. The latter most notably in The Pursuit of Happiness (2002), a wonderful film made with Anri Sala, charting the rise of a young assemblage maker to art stardom.

In this show—as in all Durham’s work—wit, wisdom, seriousness and humour are all underpinned by a profound love of both found and fabricated materials. Durham has a very particular ability to make them say and do unexpected things: whether it is a vitrine devoted to a Museum of Stones or the unholy alliance of a bedspring from the Alexander Calder atelier and two hunks of painted wood that form his Homage to Brancusi. Everyone from David Shrigley to the Abraham Cruzvillegas (the creator of the current Tate Modern Turbine Hall commission) has taken a long hard look at Jimmie Durham, who constantly reminds us that nothing is fixed and everything is up for reassessment. His revolving door set into a wall declares “Go Back/You have Another Chance”, but at the same time it takes you back to exactly the same place you started from.

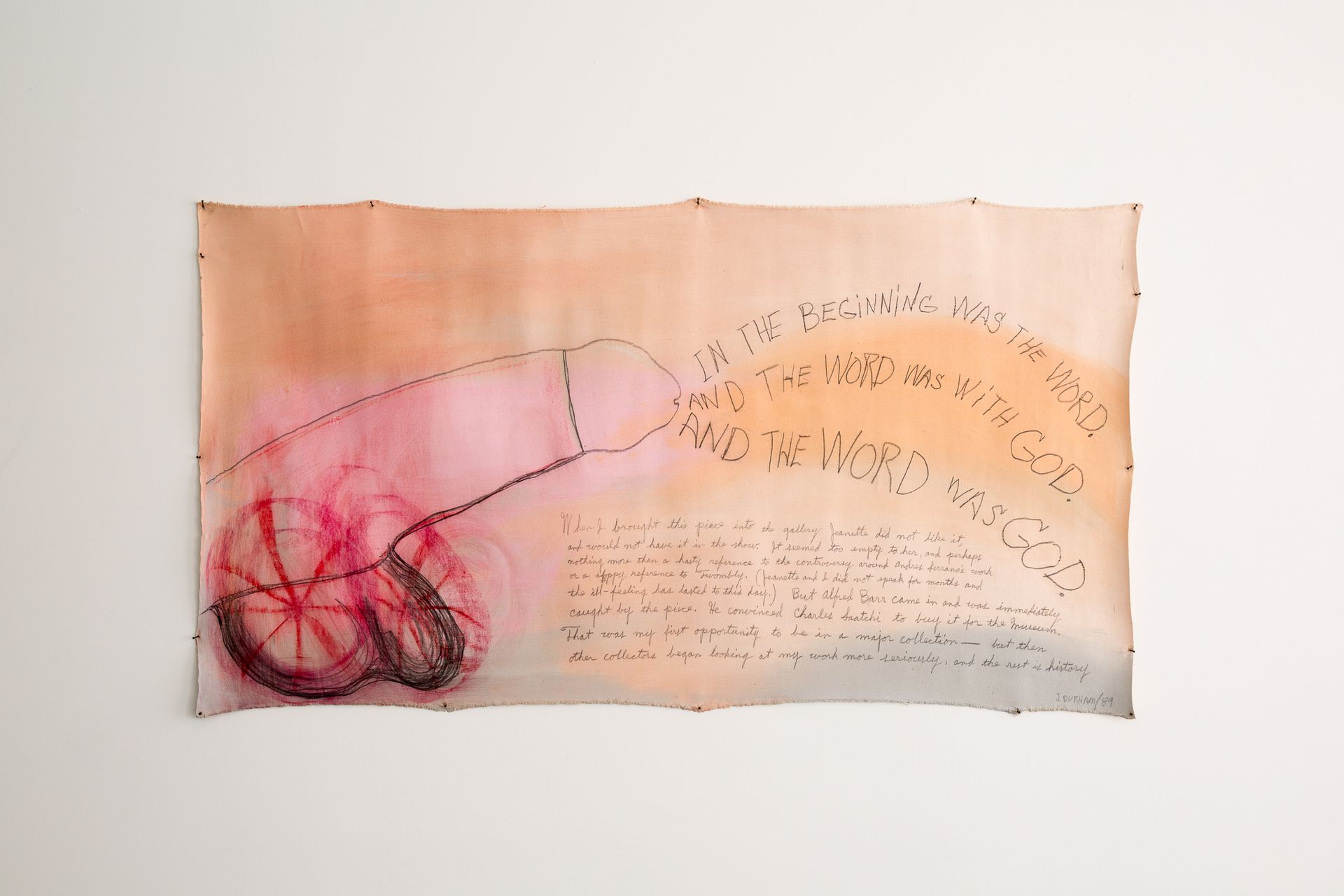

Kara Walker: Go to Hell or Atlanta, Whichever Comes First, Victoria Miro Gallery, Wharf Road (until 7 November)

Kara Walker’s paintings, drawings and silhouettes depict of the most horrific scenarios taken from the histories of slavery and colonialism. And the grimmest stereotypes that remain as their legacy up the ante to such a provocatively outrageous degree that it is often difficult to know how to react in the face of her parade of prejudice, subjugation and unspeakable acts of depraved brutality. Polite liberalism shrivels and squirms before these full on, caricatured, renditions of atrocity that unfold with a cast of extreme typecasts and a devastating eye for the absurd.

In her first show at Victoria Miro, Walker draws inspiration from Atlanta, the southern American city where she spent her teenage years. Central to the show is a giant photo that papers an entire wall with the image of Atlanta’s Stone Mountain Park, which was once the spiritual home of the Klu Klux Klan. It is now a popular theme park, with its giant granite crag embellished with a huge bas-relief of Confederate generals on horseback. Across an adjacent wall is an equally expansive cut-paper silhouette work, made in situ, in which the generals have left the mountain. They now run amok amid scenes of more wholesale horror—but ones in which the victims are often interchangeable with the protagonists and where many of the costumes are contemporary.

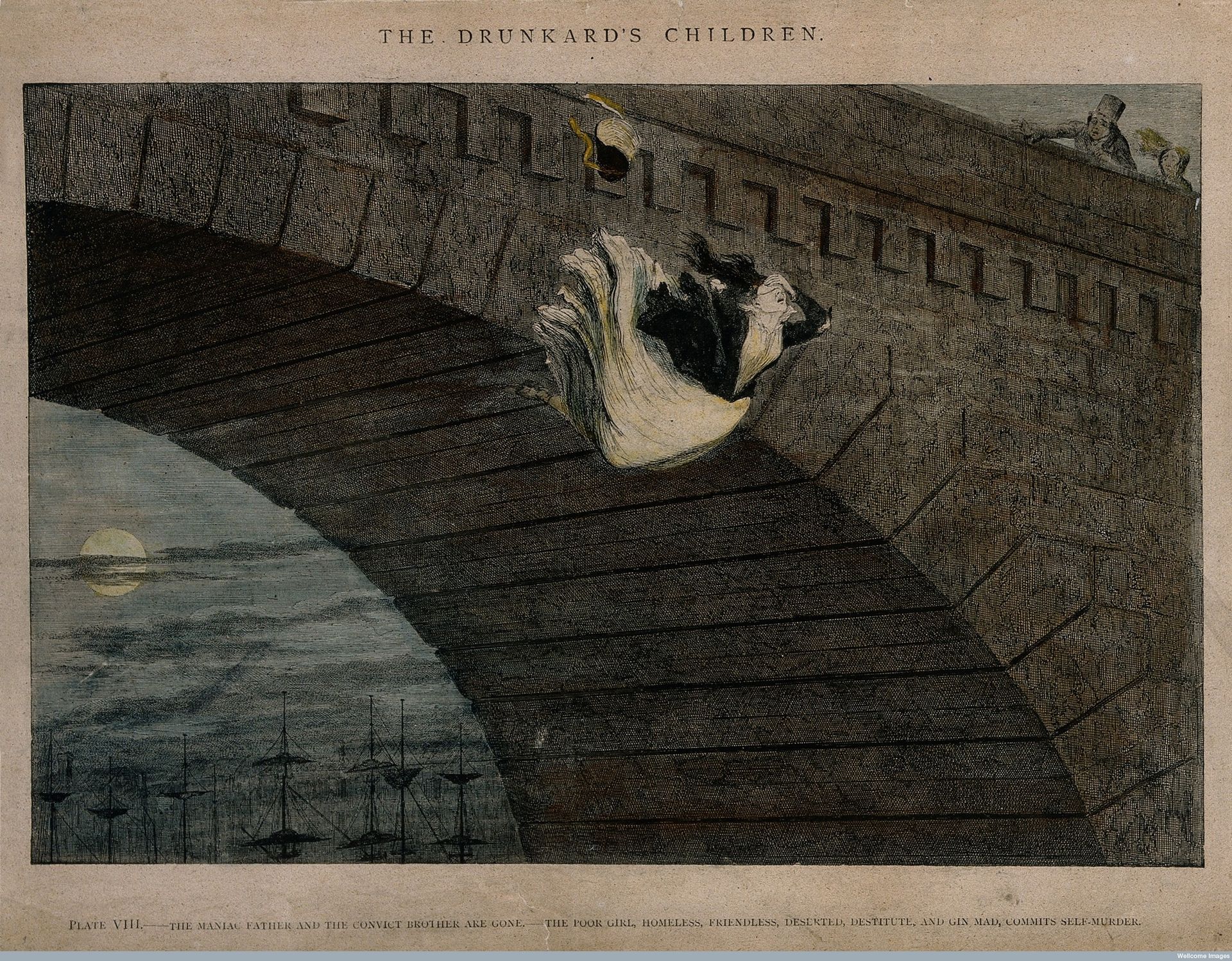

The Fallen Woman, The Foundling Museum (until 3 January)

One of my all-time favourite museums, The Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury continues to explore its dual history as Britain’s first home for abandoned children and also its first public art gallery (Hogarth and Handel were early patrons) with a thoughtful and pertinent programme. This show devoted to the myth and reality of the “fallen woman” in Victorian Britain is the latest strand. Works of ostracized and despairing women—by artists including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George Cruikshank and George Frederick Watts—show how this particularly 19th-century concept of the unmarried fallen woman. The subject, of a once respectable woman now ostracized due to the loss of her chastity, was a popular and often slightly salacious subject for artists, which at the same time helped fuel society’s harsh demonization of these unfortunate individuals. Let’s not forget there has never been such a thing as a fallen man…

What gives this show its particular punch is the way in which these fictitious fallen females are combined with the heart-rending true stories of the desperate Victorian women who petitioned the Foundling Hospital to take their illegitimate babies into care. Their pleas were often unsuccessful, with the increasingly punitive climate towards unmarried mothers having caused the hospital to change its rules mid century to focus on restoring virtue to the mother. The latter would first have to prove herself of good and salvageable character before her child would be accepted. Inevitably, an all-male committee always decided the outcome.

Elmgreen & Dragset: Self Portraits, Victoria Miro, Mayfair (until 7 November)

Elmgreen & Dragset: Stigma, Massimo Di Carlo (until 21 November)

Provocative double act Elmgreen & Dragset are currently marking 20 years of artistic collaboration with two London exhibitions, both of which show them subverting artistic conventions but at the same time infusing them with new and unexpected meanings. The fact that E & D have always banned wall labels from their own shows makes it especially ironic that their most recent series at Victoria Miro consists of appropriated museum wall labels describing the work of others. These facsimiles—involving descriptions of David Hockney, Roni Horn, Martin Kippenberger and Nicole Eisenman—are rendered in the most traditional high-art materials, including paint on canvas and the finest, flawless white marble. Like so much of their work, these “self portraits” take the marginal and unimportant and place it centre stage. Each carefully selected title represents a significant experience or emotional development in E & D’s shared life, such as On Kawara’s 15 April 1994, which marks the year that the duo met.

Over at Massimo Di Carlo another new body of work presents groupings of large hand-blown clear glass urns. These contain an assortment of pastel-coloured powders—peach, pink, mint-green, powder blue—that turn out to be the actual pigments used to coat pills in the latest generation of HIV medicines. They are arranged in groups of one, two and three, depending on the daily-prescribed pill dosage and combination of medicines. These highly appealing sweetie-coloured vessels are placed on low rectangular stainless steel plinths and play with, and off, the austere, clinical language of minimalism. They also chime beautifully with the gracious rooms and rococo plasterwork of the gallery’s Mayfair mansion home. But their aesthetic appeal and art historical resonances are also firmly underpinned by the deadly serious fact that these drugs, while prolonging life, also carry their own acute side effects. Another by-product is that because HIV is no longer considered a fatal disease, it is now no longer discussed, despite the shocking fact that one in eight gay men in London are currently estimated to be HIV positive.