If contemporary Berlin is seductively enigmatic, an assemblage of unassuming facades issuing vague invitations, the Berlin of the 1920s was by all accounts raucous and disorienting. It is this Weimar Republic-era Berlin—vivacious and dynamic, disjointed and sometimes deafeningly cacophonous—that viewers are invited to explore in the exhibition Berlin Metropolis: 1918-1933, currently on view at the Neue Galerie in New York. Founded at a time of political and cultural upheaval, the Weimar Republic made a short-lived attempt at democracy beginning in 1918 and culminating with the 1933 ascendance of Adolf Hitler. Throughout, Berlin was a turbulent cultural epicenter, exemplary of many of the changes that characterised the worldwide shift towards modernity.

At the height of the Weimar Republic, Berlin was the largest city in the world by area and the third largest by population. The growth of mass culture attended its radical expansion. US-inspired popular entertainments banned during WWI—jazz and dancing prime among them—afforded denizens of all classes a welcome artistic outlet. The bounds dividing high and low art forms dissolved as motifs culled from ragtime found their way into the work of respected composers like Stravinsky, and formerly inaccessible media like radio, cinema and a new crop of illustrated magazines became widely affordable. The so-called Neue Frau, or “new woman,” who was enfranchised and salaried, acquired newfound purchasing power.

Artistically, the Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) movement stressed the need for practical engagement and politically-inflected work. Meanwhile, the Dadaists staged comic performances and made ironic montages designed to mock the bourgeois conservatism of traditionally figurative art. The result was a bitter rejection of idealistic strivings towards beauty—and an affirmation of empty nihilism, which the Dadaists believed to be more reflective of the bleak reality of post-First World War Europe. At the same time, members of the Novembergruppe united Cubism, Expressionism and Futurism to embrace artistic radicalism in all its forms, while Modernist architects espoused a no-fuss functionalism that favored clean, unadorned facades. Mies van der Rohe’s iconic but unrealized plan for a stark glass office building, sketched in 1921, was famously defiant of the mandates of classical architecture. Like the burgeoning city, the proposed building did not unfold symmetrically around a central axis but rather splintered off haphazardly, seemingly at random.

Berlin’s growth necessitated radical spatial reconfigurations, and the ad hoc planning of the past gave way to more deliberate manipulations. High rises, traffic lanes and standardized public housing, along with the installation of a national telephone network in 1922, transformed the urban landscape. These infrastructural developments had a curious orientation, at once public and private: mass housing and transport catered impersonally to personal needs. Works like Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis highlight the sense of anonymity and alienation that distinguished the mechanistic Modern city even as it was outfitted with state-of-the-art conveniences.

Weimar-era Berlin managed to pack a great deal of artistic and technological punch into its mere fifteen years and Berlin Metropolis, whose subject matter ranges from visual art to film to architecture to fashion to photography, crams nearly as much into even fewer rooms. From the moment viewers enter the show’s first room, they are inundated with a barrage of paintings, posters and prints. Fittingly, the exhibition kicks off with an examination of Dada, and the discursive, disordered arrangement of the initial display echoes the jumble of Dadaist absurdity. On the other end of the aesthetic spectrum is the severe simplicity of Bauhaus architecture and design, to which we are treated just a corridor later. Berlin Metropolis, like the city it hopes to encapsulate, presents us with dual but opposing dangers: on the one hand, the threat of urban pandemonium; on the other, the menace of a sterilising, technocratic order.

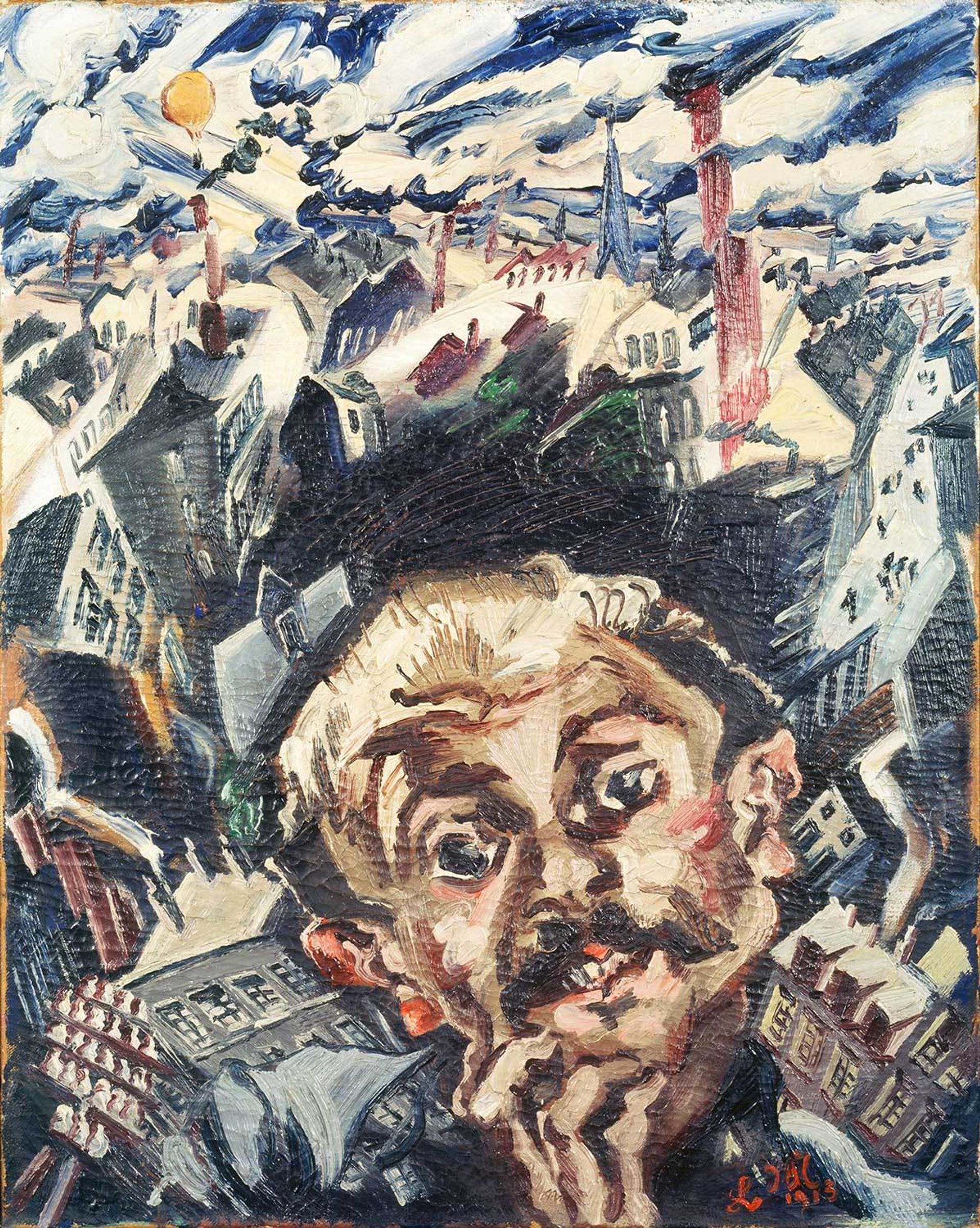

The question of how one was to navigate this new and often oppressive environment grounds the exhibition. Industrialists dominate the cityscape—and are dominated by it in turn. In Ludwig Meidner’s painting I and the City (1913) and Georg Grosz’s picture Street in Berlin (1931), the city’s occupants are visually subordinated to urban bustle, seemingly dominated by the crush of densely populated, claustrophobic streets. But in Grosz’s Of Things to Come (1922), three tycoons loom over a flattened landscape, the passive object of their sinister designs. And in Max Beckmann’s 1922 Trip to Berlin lithographs, a series of black and white caricatures of native Berliners, gangly human figures spill forth from frames even narrower than the paper on which they are drawn. These characters are afflicted not by the weight of high rises but by an oppressive impermanence and relentless pacing.

Those condemned to inhabit this schizophrenic city were marked by contradictions, and the works in the exhibition offer drastically divergent prognoses about the future of man. Humanity devolves into inhumanity in drawings, paintings, and films that conjure up deformed bodies and grotesque monsters: in Georg Scholz’s 1920 painting Industrial Farmers, a trio of rotting corpses, savagely bound together with nails, gather around an incongruously familial table. In Karl Hubbuch’s 1923 lithograph Intoxication of Lunatics, a throng of lurid ghosts recall the haunted yet humanoid villains of German films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922). In other works, inhumanity is rendered differently, this time with an emphasis on Modern man’s tendency towards the robotic. In Georg Grosz’s 1920 watercolor Diablo Player, a faceless automaton sits in a harshly angular room. The cut into his chest reveals a set of gears placed where a heart should be.

Yet advertisements and promotional images, aimed largely at the new bevy of female consumers, abound with beauty. Robustly healthy women, expertly coiffed in sleek, sporty apparel appear in works like Gerda Bunzel’s 1924 sketch Women in Evening Dress. Avant-garde artists took these glamorised portraits as incitations to satire. The Dadaist Hannah Höch’s collages, which combine magazine clippings of various body parts to create Frankenstein-like constructions, are perhaps the most apt rejoinder to the chaos of Weimar Berlin. Höch’s confused bodies fail to resolve into any definite form.

An exhibition as ambitious as Berlin Metropolis is bound to turn out a bit like Höch’s fragmentary collages, and some degree of clutter is perhaps thematically warranted. But the density can feel busy, the scope overwhelming. “The public was confronted with a seemingly arbitrary assemblage of posters, collages, and drawings,” writes the show’s curator, Olaf Peters, of the iconic 1920 Dada exhibition in the catalogue. He may well have been writing of the show he organised.

Becca Rothfeld is a contributing editor of Momus and a master’s student at the University of Cambridge.

Berlin Metropolis: 1918-1933, Neue Galerie, New York, until 4 January 2016