So many fashionable Dutch students wore the “japonse rok”—a type of dressing gown often associated with the kimono—in the mid-18th century that seeing young, robed figures carousing in the streets was a regular occurrence. But to the less cultured outsider, this was still a strange sight. One such visitor to Leiden was convinced that an epidemic must have struck the city’s youth after he spotted several students wearing pyjamas around town. Around the same time, 5,000km across the Atlantic in Boston, the American artist John Singleton Copley was painting a portrait of the local merchant Nicholas Boylston dressed in a silk robe, known as a banyan or Indian coat, and sporting a turban on his head.

This insatiable appetite for all things Asian, the legacy of which can be seen on dealers’ stands at Frieze Masters, began in the 16th century. The craze is explored in exhibitions now on in London and Boston. And this weekend Asia-Amsterdam: Exotic Luxury in the Golden Age, opens at the Rijksmuseum (17 October-17 January 2016). It explores the 17th- and 18th-century desire for Asian goods arriving in Amsterdam—“the world’s harbour”—via the mighty Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC (also known as the Dutch East India Company).

Citizens of the world

“To own Asian luxury goods in the colonial Americas was to signify your status as not only a colonial citizen, but a global citizen,” says Dennis Carr, the curator of Made in the Americas: the New World Discovers Asia (until 15 February 2016) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—the first major pan-American exhibition to consider the influence of Asian exports on the arts of the Americas. By 1573, Spanish galleons weighed down with Asian goods made yearly trips from the Philippines to Mexico, which had become a major hub for global trade.

“The first two ships to set sail across the Pacific Ocean carried 22,300 pieces of porcelain. Multiply this by 250 years of trade and you get a sense of the sheer quantities of objects exported,” Carr says. China was keen to trade porcelain for silver, which was plentiful in the Americas thanks to vast deposits in central Mexico and Peru. Although many Asian objects stayed in the Spanish colonies, others found their way to French and British colonies in North America by way of the French and English trade.

Although long-distance trade was a novel concept in the 16th and 17th centuries—and the journey across oceans to the Americas or to Europe “would have been like going on a starship to Mars”, Carr says—the difficulty in obtaining these pieces was only part of their allure. “These were new, exotic materials of unmatched quality. The quality of the pottery, for example, was much better than what was available [in Europe],” says Jan van Campen, the curator of the Rijksmuseum’s exhibition, which has been organised with the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

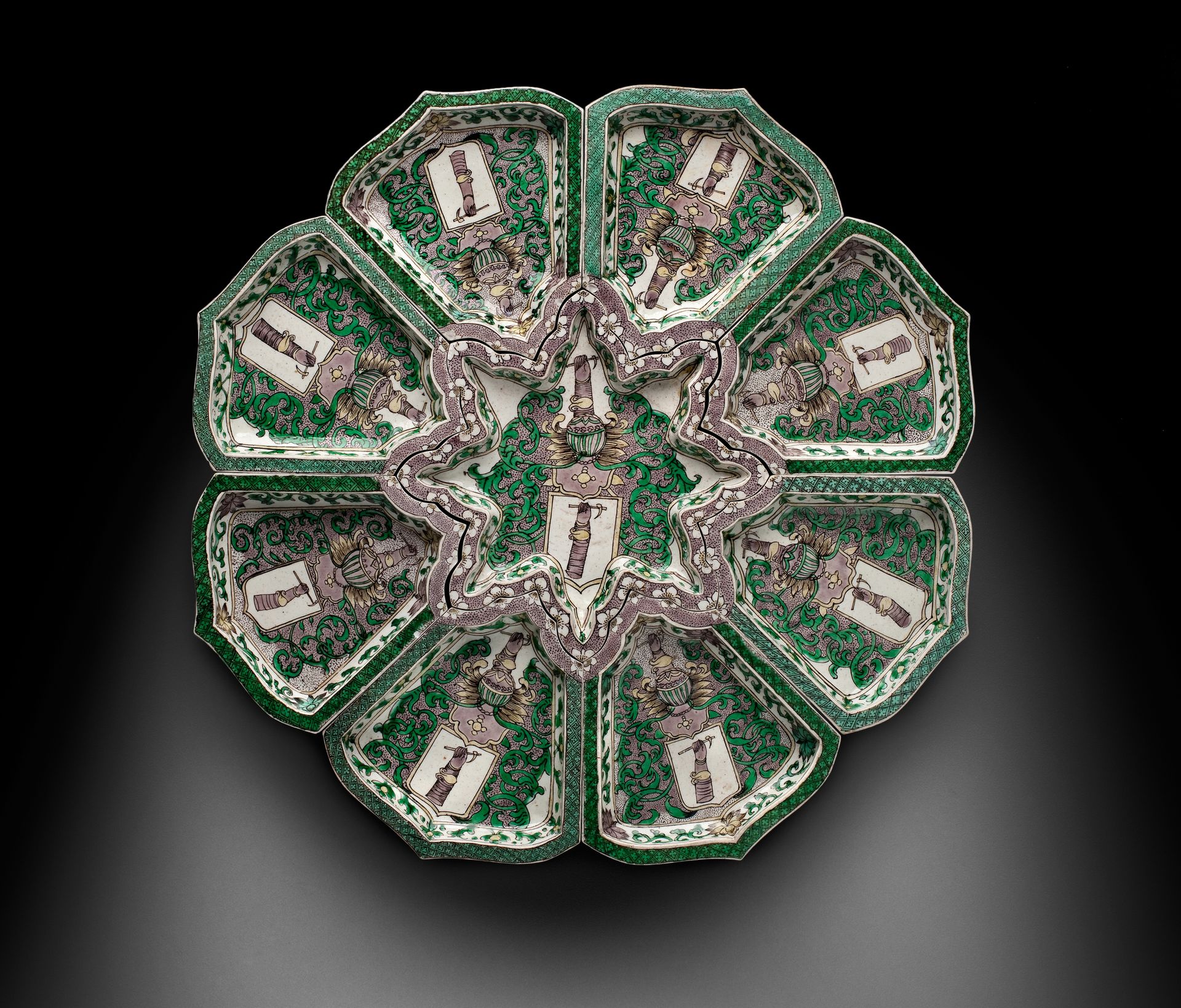

Van Campen says that the remarkably thin porcelain from China caused a sensation when it arrived in Amsterdam. “In Europe, they just didn’t know how to make it,” he says, explaining that the European production of porcelain only began in the first decade of the 18th century, in Germany. Ceramics recovered from the Witte Leeuw (White Lion), a VOC ship sunk by the Portuguese in 1613, show the range in the quality of goods destined for the Netherlands. These works were available to the elite as well to the middle classes; probate inventories reveal that people of very modest means also owned porcelain. “Sometimes it was just one broken saucer, but it shows that people really wanted to have these pieces,” he says.

The grandest objects were reserved for the extremely wealthy, such as Amalia van Solms, the wife of Frederik Hendrik, the Prince of Orange. A keen art collector and tastemaker, she amassed a sizeable collection of Asian goods, especially porcelain. She used her collection “to emphasise her high position in the Netherlands and served as an example for other well-to-do people to do the same”, Van Campen says. By decorating her interiors with Asian porcelain, she contributed to the “porcelain mania” of the early 18th century, when ceramics moved from the isolation of cabinets of curiosities to the overall decorative scheme of a room. For example, sumptuous wood and lacquer wall panels (dating from 1700 to 1720) from a house in the Hague include brackets to display porcelain.

High-priced items were also given as diplomatic gifts. Ambassadors from the Netherlands demonstrated their global reach by presenting King Gustav II of Sweden with a Japanese black lacquer and mother-of-pearl coffer in 1616, just six years after the VOC’s first shipment from Japan arrived in Amsterdam.

The founding of the East India Company in 1600—the English rival to the VOC—meant that Asian objects were widely available in England from the 17th century. The company was given a 15-year monopoly on trade to the east of the Cape of Good Hope. At its peak, the company accounted for half of the world’s trade. English ships laden with cotton, dye, opium, tea, spices and slaves sailed from ports in India and China to London.

Rosemary Crill, the co-curator of Fabric of India (until 10 January 2016) at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, says that the trade in Indian textiles goes back to Roman times, but that “it really took off” with the founding of the East India Comany. “They were importing [high-]quality materials that couldn’t be produced in Europe,” she says, adding that the story of the trade in Chinese ceramics has parallels with the Indian textile trade. The company entered the trade in Indian textiles as a way to break into the lucrative spice trade in Southeast Asia, but the firm’s focus had switched firmly to textiles by the 1670s, especially cotton textiles from Bengal.

Also popular were Indian chintzes—low-cost alternatives to woven silks. Now everyone could add colour and pattern to their wardrobes without breaking the bank. But even those who could afford to splash out on expensive fabrics were devotees of chintz, including Louis XV’s mistress Madame de Pompadour. In England, chintz became so popular that 5,000 English weavers, outraged that these imported goods were dipping into their profits, marched on Parliament in 1697. The government banned Indian plain and calico in 1701 and 1721, and issued fines of £5 to £10 to those caught wearing chintz. The ban was lifted in 1774.

Global objects

Craftsmen in Europe and the Americas responded to the influx of Asian goods by creating pieces that imitated them. Delftware, the white glazed Dutch alternative to Chinese porcelain, became an export product of its own. “Although it was made in Delft, it was seen as something that fit into this exotic world of Asian imports,” Van Campen says. In the Americas, blue-and-white majolica was a popular substitute for Chinese porcelain.

Local artisans did more than just imitate, however—they created works that mixed native and foreign influences and techniques. For example, an 18th-century desk and bookcase from Mexico boasts Asian, German, Dutch, Islamic, Spanish and indigenous Mexican influences. “This is a truly global object that could not have existed before the 16th century, when all the great land masses of the world were finally communicating through trade,” Carr says. “Although people think of globalisation as a new concept, it has its roots in the 16th century. It is the pieces that were being taken from place to place, and influencing artistic production along the way, that are the most interesting objects from this period.”