As diplomatic relations slowly thaw between Iran and the West—with the nuclear deal signed by Iran and the US in July the most crucial development—established and emerging Iranian contemporary artists are making their presence felt in London.

The London-based dealer Vassili Tsarenkov believes that, “because of the exceptional quality by international standards of contemporary Iranian art”, there are many more artists whose work deserves to be better known abroad. A former manager of the St Petersburg Gallery in Mayfair, Tsarenkov is a co-founder of the Sophia Contemporary Gallery, which plans to open a space in Mayfair in February for contemporary Middle Eastern art, with a focus on Iran.

“Through numerous research trips in Iran and other countries, we have handpicked both established and emerging artists at different stages in their careers and working with a wide range of media,” Tsarenkov says. “A few galleries represent artists from the region; through our research trips, we have found a wide range of artists who deserve representation on an international scale.”

Lesser-known figures such as Pooya Aryanpour and Azadeh Razaghdoost, both based in Tehran, will be part of the gallery’s roster, along with established artists such as Reza Derakshani, who lives in the US. “The Tehran art scene is thriving today, and many artists grew up connected to current trends in the international contemporary art world while being firmly grounded in the 1,000-year-old, incredibly rich Iranian culture,” Tsarenkov says. The gallery’s co-founders are the Russian art adviser Lali Margania and Lili Jassemi, a graduate of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.

Some of this activity is filtering into Frieze London. Work by the Tehran-born photographer Shirana Shahbazi is available from the Breeder (FL, H14), an Athens-based gallery, while the Third Line (FL, H2), based in Dubai, has brought Backyard Wars (2014) by the Vancouver-based artist Babak Golkar to the fair. The work is a striking metal model airplane that has been taken apart and reconstructed. Golkar says that the work was inspired by the avant-garde visual language of the Russian Constructivists. “Backyard Wars also refers to the Cuban missile crisis and its trajectory—no pun intended—to date,” he says.

Golkar was a finalist in the 2011 Magic of Persia Contemporary Art Prize (Mop Cap), a key award for emerging Iranian artists that was founded by the London-based Magic of Persia Foundation in 2008. Mamali Shafahi, who lives in Paris and Tehran, is a finalist this year. His video Maybe/Public Love (2015), the second part of his full-length film Nature Morte, was submitted for the prize. He says that the themes explored in his work, made in a variety of media, include “fame and narcissism, intimacy and the invasion of privacy”.

“The political changes are very recent, so I wouldn’t say that the difference can already be felt,” Shafahi says. “The existing interest in Iranian art may, however, be boosted. In the longer term, we obviously hope that Iranian artists will [be able to] travel more easily for exhibitions, residencies and so on. But if the economy opens up, that will presumably also have an effect on the Iranian art market, not least in simply opening up banking relations.”

Shiva Balaghi, a visiting scholar at Brown University, Rhode Island, in the US, was among the panellists who shortlisted 20 artists from 250 nominees for this year’s award. Balaghi says that the hundreds of submissions make the prize “like an ethnography of the Iranian art scene”. She has been mapping the development of the Iranian contemporary art scene and says that there is now a greater exchange of ideas and movement between artists at home and abroad.

“Artists in Iran use the internet to keep up with the developments of their diasporic counterparts and vice versa. Curators often show them alongside one another, and the artists themselves move back and forth. Some artists, like [Parviz]Tanavoli, make art in studios in Iran and Canada, as did the late Sadegh Tirafkan,” she says.

Balaghi singles out artists such as Vancouver-based Kambiz Sharif, who opened a sculpture school in Tehran in 2001, and the calligraphy-based artist Pouran Jinchi, who is represented by the Third Line and by Leila Heller Gallery in New York.

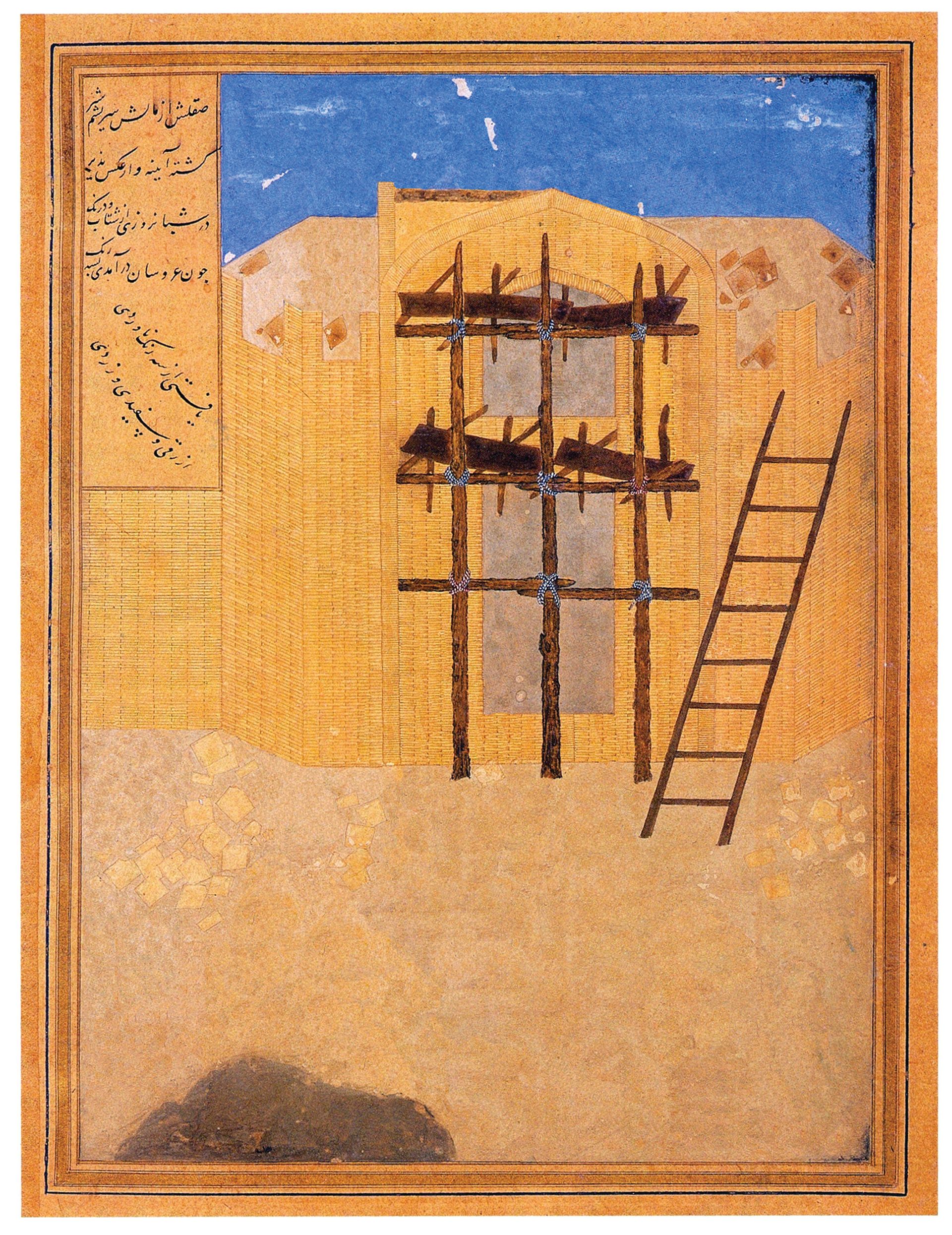

The Copperfield gallery in London is presenting the first UK solo exhibition of the Iranian-born, US-based artist Shahpour Pouyan (until 13 November). The 17 new works include a crucifix made of batons, Memorial Cross for Pope Urban VI (2015), and a series of reconfigured Persian miniatures showing historic scenes with the key figures and protagonists missing, such as After ‘Building of Castle of Khawarnaq, Kamal Al Din Bihzad, 1494 AD’ (2015).

“The moment felt right for the exhibition because some of the historical references in the work have interesting connections and parallels with current world events, attitudes and outlooks,” says Willam Lunn, the director of Copperfield. “For these reasons, Pouyan is increasingly being recognised by critics and institutions, with a forthcoming exhibition at the prestigious Grey Art Gallery at New York University.”

Other artists of note include the Iranian photographer Newsha Tavakolian, a Magnum nominee, who was named as a Prince Claus Laureate winner in September (she donated part of her award to charities helping Syrian and Iraqi refugees). Her photographs and the work of another young Iranian artist, Hojat Amani, have been acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Another artist making strides is Brooklyn-based Afruz Amighi, whose work refers to traditional Islamic art. In 2009, Amighi was the inaugural recipient of the Jameel Prize, awarded for contemporary art inspired by Islamic tradition. Her work Hanging (2011) is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.