Pop art has always had an edgier side, one that unsettles the surface gloss of kitschy Coke bottles and Ben-Day dot comics. In 1964, the performance artist Dorothy Podber smuggled a revolver into Andy Warhol’s New York studio and fired a bullet through the foreheads of a freshly painted stack of his Marilyn Monroe portraits while the artist looked on in paralysed horror. Podbear’s audacious assault not only wiped the smirk off Warhol’s work, it also rescued the series from being yet another smug example of High Art Lite by loading the portraits with a meaning far more in tune with the violence of the age than they were otherwise capable of conveying.

One may be reminded of Warhol’s Shot Marilyns by a trio of distressed paintings in the final room of the exhibition The World Goes Pop at Tate Modern in London, which reveals Pop Art’s more complex dimensions. The works, from the Post Art series by the Moscow-born, New York-based collaborative artists Komar and Melamid, depict a sequence of well-known Modern art images (a Campbell’s Soup Can by Andy Warhol, a comic by Roy Lichtenstein and an insignia by Robert Indiana) in a state of suspended decay, as if salvaged from some acidic abyss where they've been decomposing for centuries. Burnt, rusted and crumbling, these fragile fragments of famous paintings that can today command some of the highest prices prices at auction are barely legible and appear to be the relics of a violently extinguished society.

We are accustomed to seeing the original works in pristine, retail-ready condition so their fantasized ruin in Komar and Melamid’s work is jarring. These unnerving, vestigial paintings, which resemble excavated frescoes of an extinct civilization, issue from the imagination of former Soviet subjects at the very height of the Cold War. They offer a brutal comment on the perishability of our consumer culture and challenge what we know about Pop art's ability to enshrine and ennoble the disposable signs of popular media. They are encrusted with wry political commentary that the original works can neither conceive nor concede.

Had I organised this wonderful show, I would have placed Komar and Melamid’s series at the very beginning, rather than at the end of the exhibition, because it crystallises many of the key themes explored throughout. The exhibition, which spreads across ten rooms and includes 160 works from the 1960s and 1970s by 64 artists, deepens our appreciation of Pop art’s cultural reach by revealing how artists (particularly female artists) from around the world employed a new visual vocabulary to respond to acute social and political crises beyond the ephemeral commercial centres of Madison Avenue and Hollywood. There are no works by Warhol here and none by Lichtenstein. Nor are there any by Richard Hamilton or Allen Jones. Instead, the curators have set fire to the overly-familiar façade of Pop art to reveal something starker smouldering underneath.

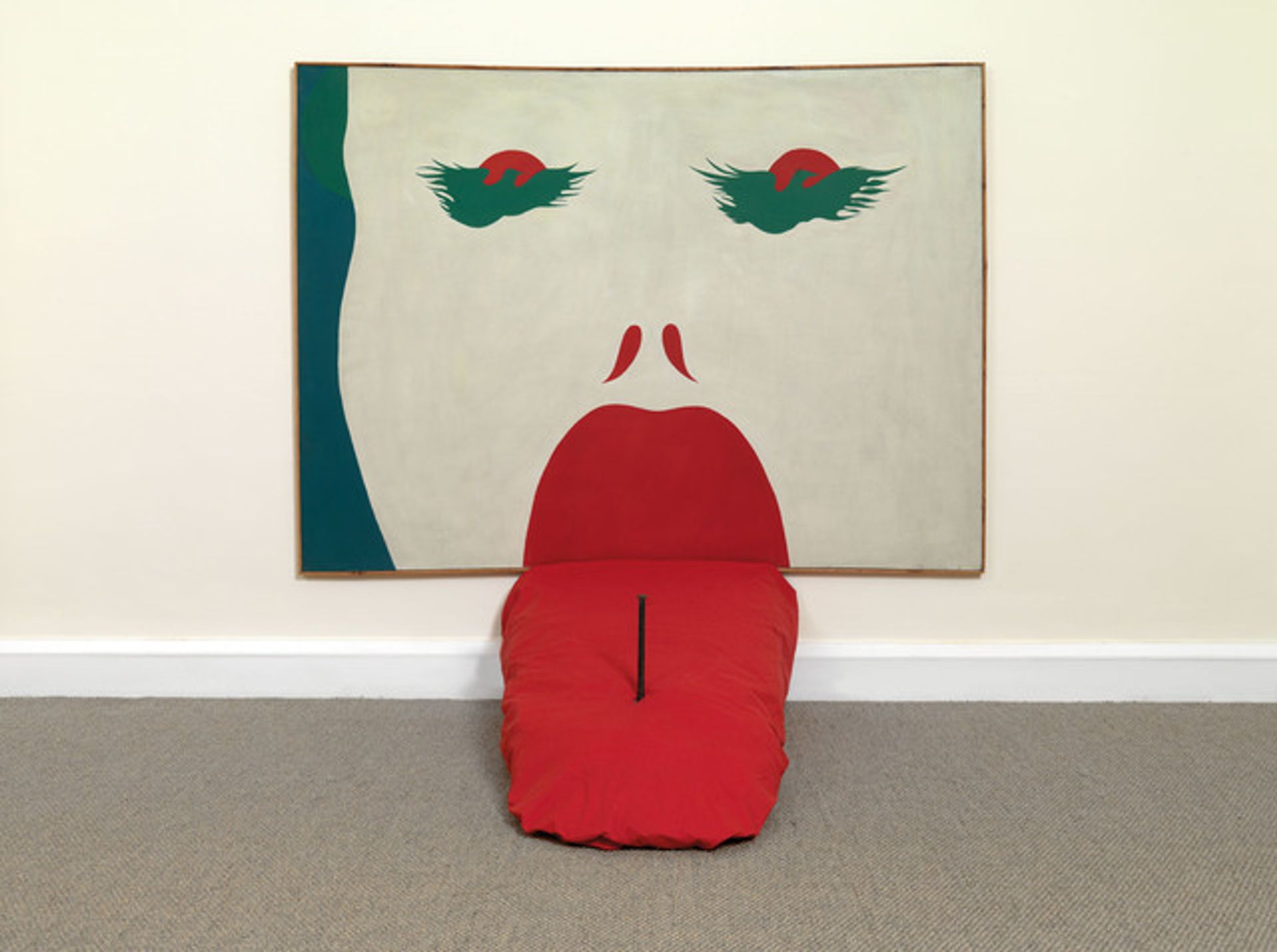

What greets visitors in the first room of the show is nevertheless effective: a combine by the Polish artist Jerzy Ryszard “Jurry” Zieliński titled Bez Buntu (“Without Rebellion," 1970). At first glance, the hybrid work, with its outsize lips and preposterously protruding tongue, is strangely familiar; it resembles the Rolling Stones’s lip-and-tongue logo that was designed by John Pasche that same year. But Zielinski’s long, lolling lick isn’t wagging at us in Jaggeresque defiance, but rather is pinned to the floor of the gallery by an enormous steel stake. Whatever sexy allure the work may have had is hammered out by the violence of the enormous nail: a clear comment on Eastern-bloc censorship in Zielinski’s native Poland and beyond. Above the open lips, the flirtatiously flapping eyelashes are suddenly seen for what they are: a pair of birds in full-wing, the dream of freedom flying away.

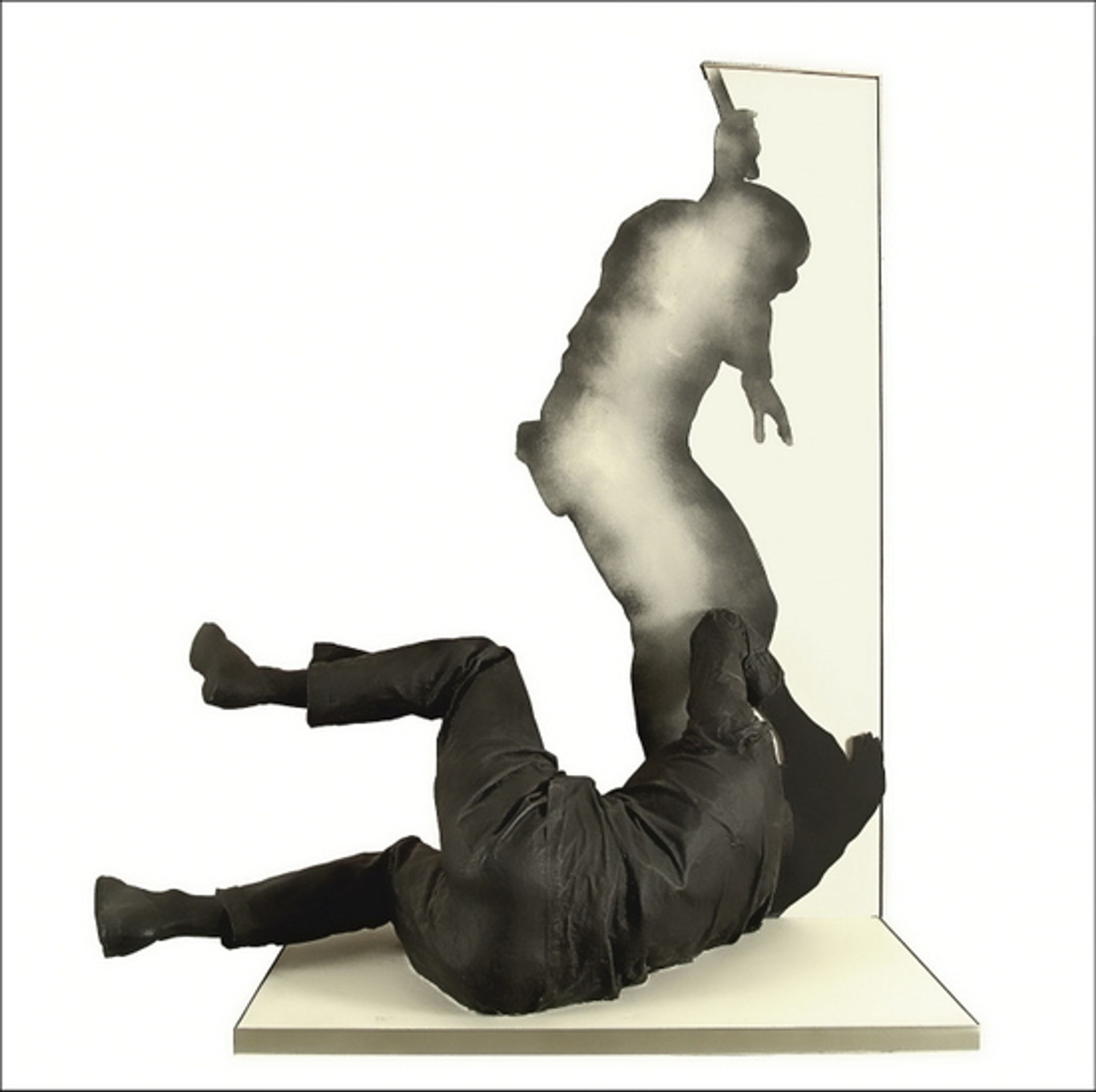

Each room in the show is devoted to a theme: “Pop at Home,” “Pop Bodies,” “The Pop Crowd,” “Folk Pop.” In an early gallery devoted to “Pop Politics,” the works challenge our assumptions about Pop’s seeming indifference to geo-political struggles. Among the most striking pieces here is another combine, this time by the Spanish artist Rafael Canogar. On the flat surface of El Castigo (“The Punishment,” 1969), is the silhouette of a riot-squad police officer brandishing a baton above his head, poised to deliver a blow. Just below him is a collapsed figure, writhing in pain, spilling out from the painting into the gallery space.

The work has all the sharp stylistic sense of Pop, but with the addition of incorrigible violence. On one level, it is a comment on the totalitarian tactics of Francoist Spain, which Canogar witnessed first hand. But its meaning is not tethered to the particularities of that context. It also transcends its historical resonance and survives as an enduring response to the assault of mass-media iconography, brutally forcing viewers to succumb to its manipulative message.

Perhaps the most surprising and welcome aspect of the exhibition is its exploration of the role that women artists played in the story of Pop. The movement has often been derided for its unapologetic objectification of the female body. In Britain, Allen Jones’s perverted furniture of bondaged female bodies pretzelled into tables and chairs remains among the most frequently cited examples of the movement. Considering work like this, Pop art’s coincidence in the 1960s and 1970s with Second Wave feminism has always been one of history’s less amusing ironies. But the density in this exhibition of compelling works by women artists from Latin America, Eastern Europe, Asia and the Middle East provides another narrative and suggests that the chauvinistic gaze so often associated with Pop was regularly rebuffed by contemporaries.

Two works from 1968 by artists living half a world away from each other reveal how quickly Pop spread across the globe as a viable language for critiquing the objectification of women. Nicola L’s Woman Sofa (1968) is a shiny grey vinyl couch onto which the severed parts of a female body have been heaped, like awkward throw-cushions. The result is a work that purports to be domestically useful but which, in fact, uncomfortably psychoanalyses (or puts on the couch) a long tradition of misogynistic staring and Cubist dismemberments.

In the same year that Nicola L was fashioning her acerbic sofa, the Peruvian artist Teresa Burga was likewise busy breaking down the female form into elements of stylised absurdity. Cubes (1968) is made of six brightly-coloured square hexahedrons that resemble a cross between oversized infant building blocks and Warholian Brillo boxes. The 36 faces of Burga’s sculpture are variously decorated with bold geometric patterns and with stylized fragments of the female form. Stacked haphazardly on the gallery floor, like a tumble of dice thrown by an unseen hand, the work suggests that the role of women in visual culture has always been a gamble, a toss that jumbles dignity and design, ornament and identity. As with the most intriguing pieces in this important show, Burga’s work shows that Pop Art always had a multitude of sides and was a more heavily loaded cultural game than we typically admit.

Kelly Grovier is a poet and art critic. His new survey, Art Since 1989, will be published in November as part of Thames & Hudson's World of Art series.

• The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, London, until 24 January 2016