In 1958, the photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank published a collection of photographs called The Americans that took a new approach to picturing the country’s people. These were drive-by photographs before the term existed, a road movie in still pictures. It took a year for the pictures to get much notice in the US, but once they were visible, Frank was accused of hating America. On the road, while shooting, he was harassed by police in small towns where a foreign accent was a liability, even in the twilight of McCarthyism (Frank emigrated from Switzerland to the US after the Second World War). By his own account, he was a champion of the imperfect US. “Coming from Europe, this was a great country, because everything was open, all you had to do was try,” he recalls in the new documentary film Don’t Blink: Robert Frank, sounding like a Republican if you separated his words from his pictures.

The Americans is a near-infinite field of inquiry. No visual history of the 20th-century US can leave them out. The project belies Frank’s observation that “a photograph is just a memory that you put in a drawer.” Since it was completed, Frank had done—and is still doing—much more. The documentary, directed by his collaborator and longtime editor, Laura Israel, takes audiences through his life and work, with plenty of his wry commentary about both.

The film takes on Frank’s biography chronologically, beginning with a glimpse into his family home in Zurich. We see Frank’s first photograph, of a church in Zurich, head-on, decades before the German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher made a career out of similar work. We also see the photographs his father took and his huge camera, encased in wood, heavy and immobile. The movie careens through Pull My Daisy, a 1959 film directed by Frank and Alfred Leslie and featuring the beat writers Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Jack Kerouac. This movie set a tone that carries throughout Frank’s work: satirical, playful, irreverent, and produced for what looked like ten cents. Experimental cinema back then tended to be formal, academic or ethnographic. This film, with its sexually suggestive title, was fun and games, like much of what the Beats did. Frank joined that family.

With his real family in the 1970s, Frank bought a house on a bleak windswept hillside in Nova Scotia that reminded him of Switzerland. Here, he made raw, honest, personal films that reflect his sometimes dreary situation, as with the loss of his daughter in a plane crash in 1974 and the suicide of his son in 1994. "Life dances on, even on crutches," he says.

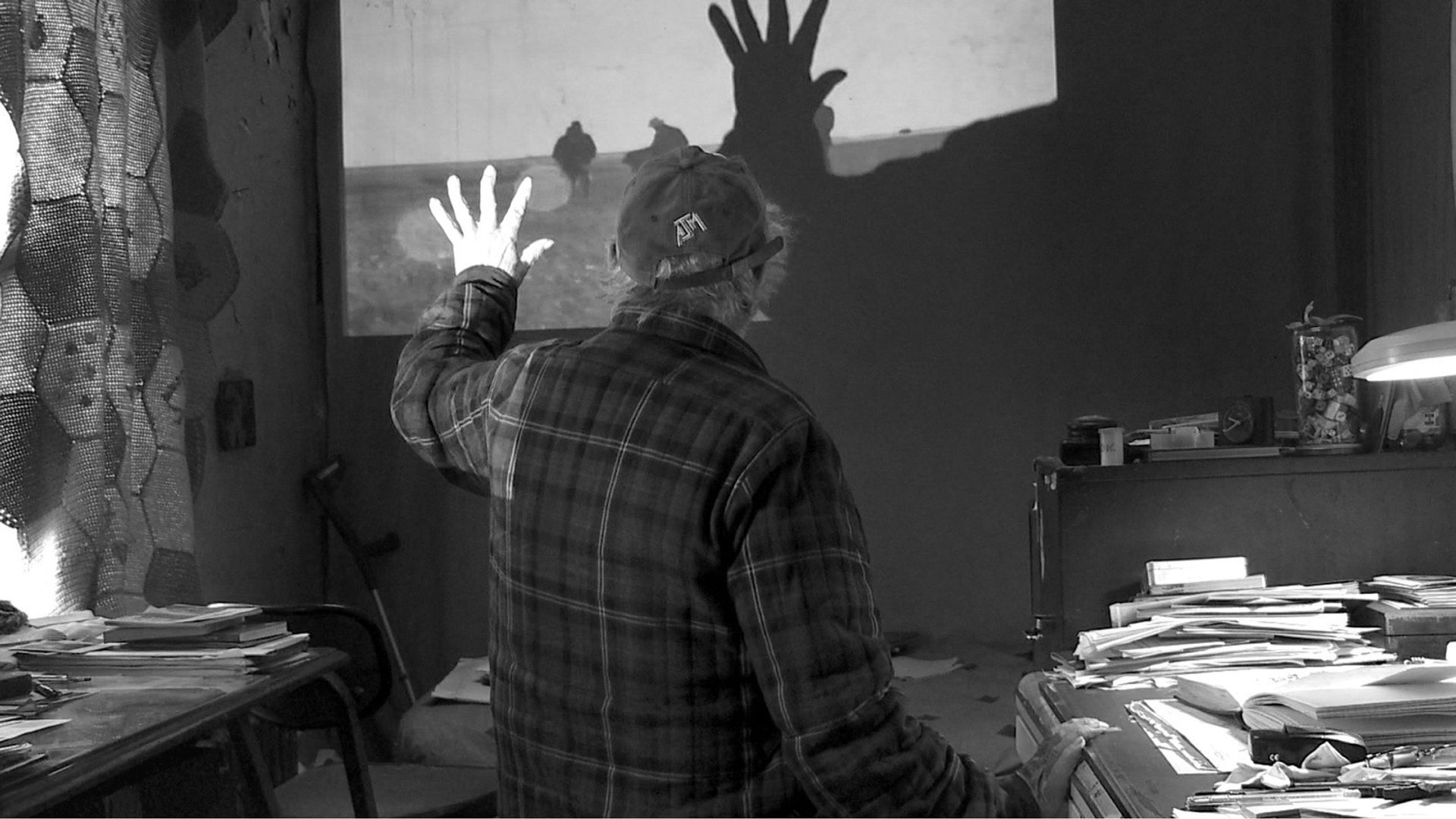

Throughout it all, Frank’s process also emerges. He discusses how his early photography was subsidised by Harper’s Bazaar, where he started working in 1947. We also see him writing and scraping on negatives. (His “darkroom man,” Sid Kaplan, explains these mechanics, which evolved over decades.) Frank looks at contact sheets for The Americans, saying that he could rarely use more than one image per sheet, and that a first take was usually the best, since a subject changed once he or she became aware of the camera.

In past interviews, Frank has been a curmudgeon, scolding interlocutors for questions that he found to be “a fucking echo.” Yet with Israel, over the course of filming Don’t Blink, Frank grew comfortable enough to make jokes, although the humor tends to be dark. Yet Frank, always the exception, warms to Israel’s camera. Even Nova Scotia (and especially his friends there) takes on an improbable charm.

Don’t Blink is not helped by its music. It tends to overwhelm what is shown on the screen. Yet audiences who see the film more as celebration of Frank than as a critical contemplation will swallow this film whole. It is not definitive, but it is an entertaining visit with an accomplished man.

David D’Arcy is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper.

Don’t Blink: Robert Frank, directed by Laura Israel, is playing at the Film Society at Lincoln Center as part of the New York Film Festival on Sunday 4 October and Tuesday 6 October.