Miuccia Prada is the conceptual fashion leader in a conceptual art world and her firm showed the way where most of the other luxury brands have since tried to follow: art entwined with shopping. She works with starchitect Rem Koolhaas’s think-tank OMA, the curator Germano Celant and artists in the creation of her worldwide network of shops (correction: “epicentres”) and the Prada art centre in Milan.

More dynamic than any official museum in the city, they have made a multi-purpose art village in old factory premises, where the predictability of contemporary art centres is subverted (it opened in May 2015 starring an exhibition of ancient Roman sculpture), and the public is invited in free.

2008 The year of boom and bust in finance included one emblematic episode of market manipulation in the art world, too. A collection of Chinese contemporary art unveiled to the public at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark in 2007, published in two glossy catalogues partially funded by the institution and with contributions from leading scholars, was then sent for display to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Just two days after the show closed there, in March 2008, Sotheby’s announced that all the art was to be sold in Hong Kong. Neither the Louisiana nor the Israel Museums were aware of the plans to flip the works. The so-called Estella collection consisted of 200 works by 69 artists, assembled between 2004 and 2007 by the dealer Michael Goedhuis for two directors of Weight Watchers.

It was bought by New York dealer Acquavella in 2007 and Sotheby’s also had a stake in it. At the auction, the works fetched $17.8m (est $12m), with private Chinese, Hong Kong and Asian buyers to the fore.

2007 The impetus given to the Middle Eastern art scene by Christie’s first sale in Dubai, in 2006, which totalled $8.5m and proved that there were buyers for art from the region, was given extra power by the decision of Abu Dhabi to invest in a franchised Louvre, to which 300 works will be lent from Louvre’s and other French museum collections over 10 years.

The new museum, to show “comparisons between works of various periods and geographical origin, with an emphasis on the dialogue between civilisations”, in a spectacular building by Jean Nouvel, will open in 2016. The Gulf emirate is paying €1bn over 30 years to a new body, the Agence France-Muséum, that administers this capital sum for the benefit of a consortium of participating museums. A national museum in memory of the founder of the UAE, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al-Nahyan, and to tell the history of the country and region, is due to open in 2016, in an even more spectacular building by Foster + Partners.

The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, yet another potential franchise of the New York museum, also agreed in 2007, has been forming a collection, but its building, designed by Frank Gehry, has yet to break ground. Since then, the turmoil in the Middle East and its effect on the West have fired up interest in the region and reinforced the spontaneous development of activities in art, dealing, museums and biennales.

2006 Claims for the restitution of art stolen from the Jews by the Nazis began to be made in the early 1990s and have since shaped museum policy and how due diligence is exercised when pre-war works of art come up for sale. The most famous case, a true David v Goliath turned into the 2015 movie “The Woman in Gold”, is that of the Bloch-Bauer Klimts. These five paintings, including a famous portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, were confiscated by the Nazis and ended up as star pieces in Vienna’s Galerie Belvedere. Maria Altmann, 89-year-old niece of the original owner, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, sued the Austrian state, which required her first to get a judgment in the US Supreme Court rejecting Austria’s claim of immunity as a sovereign nation. In January, an arbitration panel in Vienna decided in her favour. A few months later the New York billionaire Ronald Lauder paid a reputed $135m for the golden portrait of Adele and it hangs now in his New York museum, the Neue Galerie.

2005 Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani, at the time probably one of the greatest collectors in the world—and certainly in the Middle East—fell from grace with his cousin the Emir of Qatar and was put briefly under house arrest. This was a great loss to the country’s museum plans because the sheikh had the true collector’s passion, eye and instinct.

His sin was highly irregular accounting in his purchases for the National Council for Culture, Arts and the Heritage (NCCAH), of which he was chairman from 1997 to 2005. With some confusion between the future museum collections and his own, he bought Islamic art, textiles, Egyptian antiquities, natural history prints, precious stones, jewellery, fossils, narwhal tusks, entire libraries, photographs and vintage cameras, Roman antiquities, Art Deco furniture, statues, vintage cars, antique bicycles and 18th-century French furniture.

Although never reinstated, he was soon released and returned to his collecting habits. In a rare interview, he had told The Art Newspaper: “’I want visitors [to the museums] to see the very best, or nothing at all.’… and he often said that what he was trying to achieve would not be understood in his lifetime”. The exquisite Museum of Islamic Art, by I.M. Pei—Sheikh Saud’s choice—opened on 22 March 2008; his name was never mentioned in any of the speeches. He died, aged around 48, on 9 November 2014.

2004 Despite tensions between the West and Iran over its nuclear programme, cultural exchanges between academic institutions and museums continued. The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago repatriated archaeological artefacts, and the university was part of a team of Iranian archaeologists working on a new dig near Persepolis. Bacon’s triptych of two figures lying in bed with attendants went on loan to the Tate from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran, while the British Museum was to hold the major exhibition “Splendours of Ancient Persia” in 2005, with numerous loans from Iran. This led to the famous Cyrus Cylinder being lent by the museum to Tehran in 2010.

2003 The sacking of Iraq’s National Museum by the local population after the allies invaded Iraq was a harbinger of the indescribable chaos, murder and destruction that awaited the country. The ransacking took place over four days from 10 April as US troops stood nearby but failed to intervene. In Mosul, the museum and university library were also sacked and the Baghdad National Library and Archives were burnt.

The Art Newspaper immediately got hold of a copy of the only book with numerous images of objects in the Iraq museum and put them online to help dealers, international police and customs identify them. Around 15,000 items out of total holdings of 170,000 were looted, of which about 10,000, many of them cylinder seals, are still missing. International opposition to the war coalesced around this episode, with the British Museum playing a major role in explaining the importance of the cultures the museum encapsulated and in assisting its Iraqi colleagues.

The National Museum reopened 12 years later, in February 2015, shortly after Isil destroyed sculptures in the Mosul Museum too large to have been looted in 2003.

2002 Documenta, the international exhibition in the small German town of Kassel that every five years invites us to think about some of the toughest examples of contemporary art, responded movingly to a world deeply unsettled by the 11 September attacks and the drums of war sounding from the US. It was a mighty denunciation of violence, poverty and social dissolution, with no sex, no bodily fluids, no gender politics, no irony, and hardly any direct references to the unfolding catastrophe.

Its curator, Okwui Enwezor, chose serious artists dealing with serious matters from all over the world. Painting was almost abandoned; video, documentaries and photographs abounded. Some critics hated it for being too explicitly sociological and political, not allusive and “artistic” enough, but it was what was needed at that moment and reminded the art world of the vast areas of life beyond art.

Since then, the Western art scene has opened up to the Middle East, Asia, Africa and Latin America and the hegemony of Western art has ended, at least in museums.

2001 On 11 September, Lucio Pozzi, one of our New York correspondents, himself an artist, wrote: “Today I painted a little landscape, copied from the photograph of a work of mine...I feel that the delicate vulnerability and the uselessness of a little picture like this are an answer to horror.

“It is not an evasive gesture, nor an act of hope or defiance. Art does not change the politics of the world. Art will never convince our rulers that acting towards the millions of poor, sick, dying and hungry who live outside our gilded walls is both charitable and the best self-defence. A European artist friend said to me: ‘At this point, one can’t carry on making art.’ I answered: ‘Today I have painted a little watercolour and I shall paint another one tomorrow.’

“Let us not delude ourselves: that which we call art no longer fulfils the tasks with which it was once charged, but the forces of evil cannot overcome even the humble paint-tiddlies of a backyard artist. And that is so precisely because these fragile painted surfaces serve no purpose…They are like the mute scream of freedom that a prisoner sends out when paper, pencil and all the means of making art have been taken away, yet despite everything he spits on the floor and draws in the dust with his finger, giving himself another day of thought that the guards cannot steal from him.”

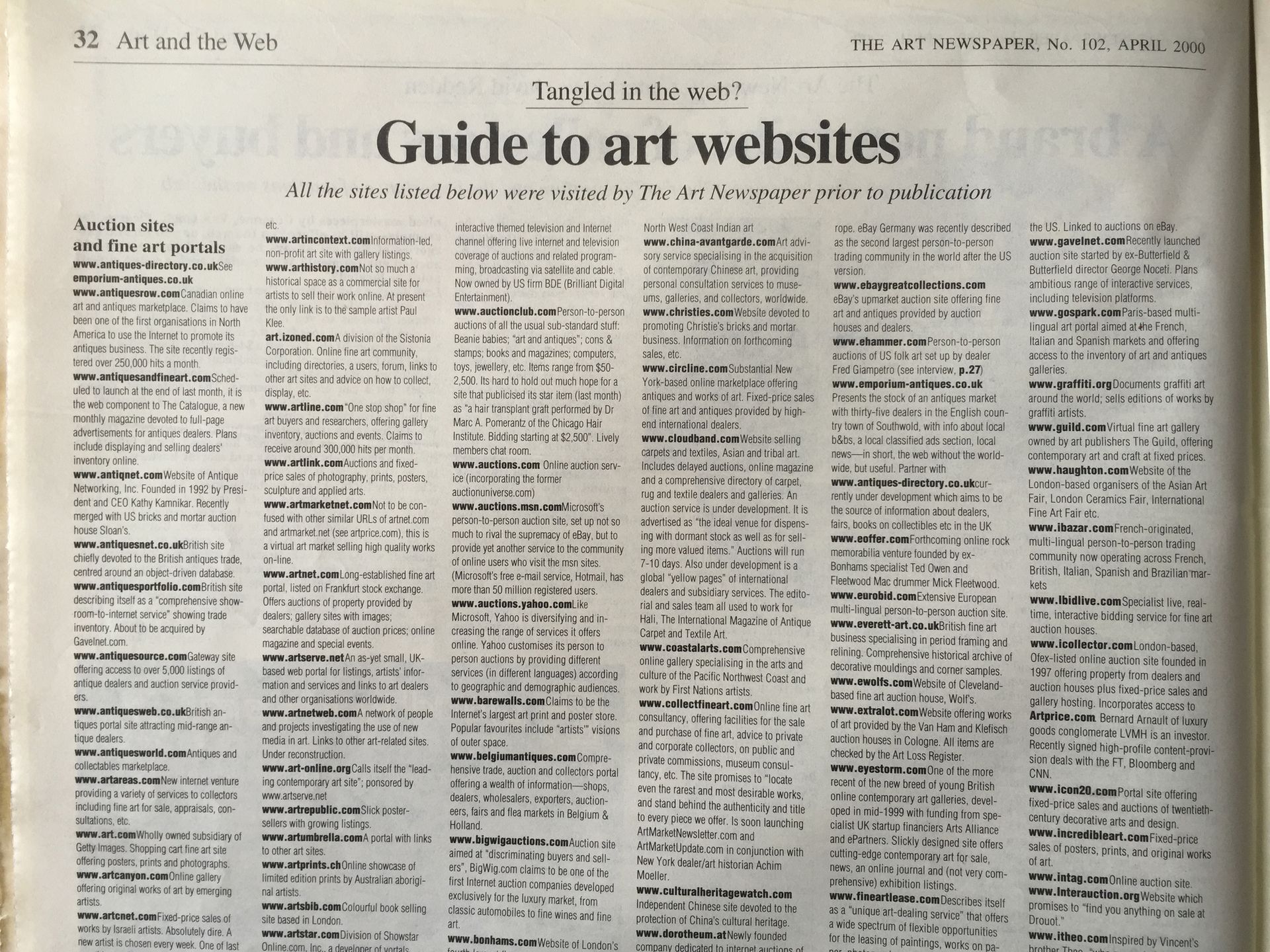

2000 We published a double-page spread listing all the online auction sites that, at the time, were proliferating. We were sceptical of the level of financial exuberance surrounding this growth as more and more and more supporters announced the death of the art world as we knew it. Unsurprisingly, almost none of the websites listed exist anymore, confirming our belief that, while the online art market certainly has a place in the art world—and that place is still being defined 15 years later—it will not replace bricks-and-mortar businesses, at least not any time soon.

For stories from our first decade, 1990-99, click here

• Tickets to our 25th anniversary celebration at the British Museum on 28 October, where eminent cultural figures will debate the question, "What is art for?", can be booked online now.