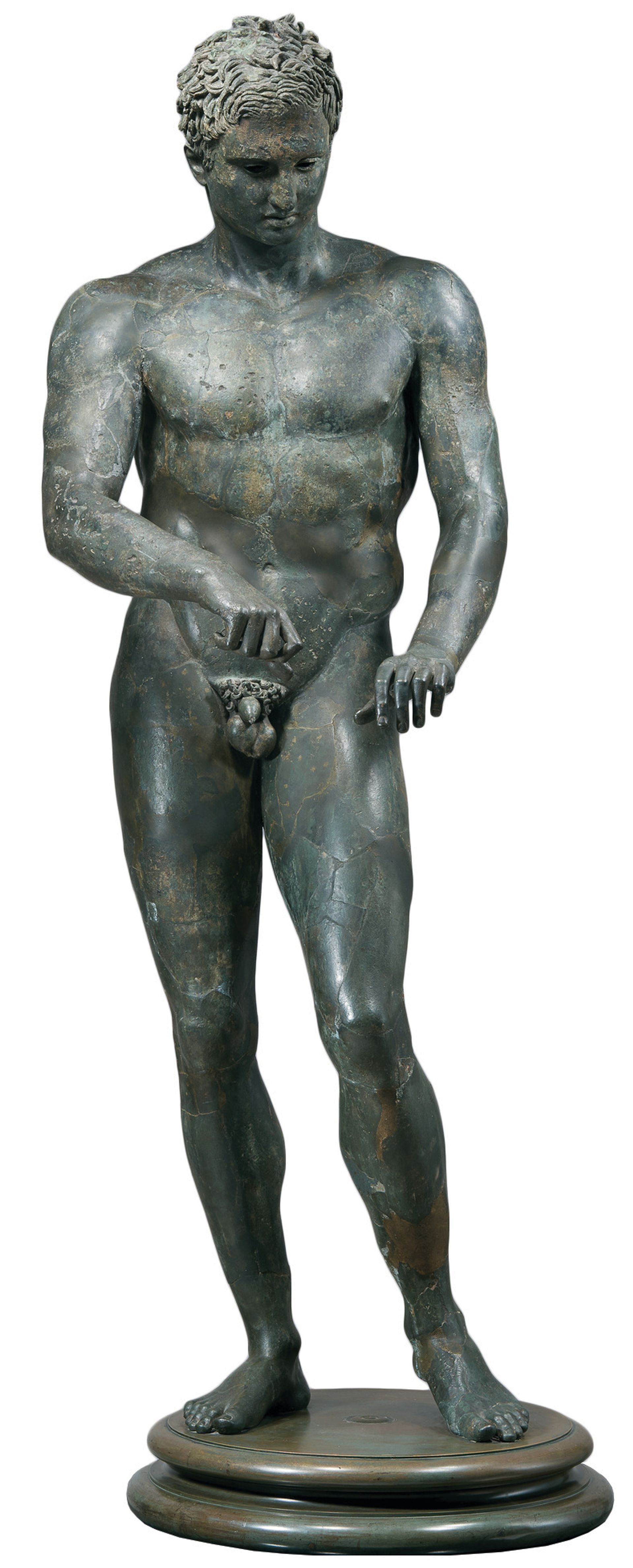

Two ancient Greek bronze figures known as Apoxyomenoi that look like long-lost but not perfectly identical twins are on show together for the first time at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The exhibition Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World (until 1 November) unites intimately related sculptures that have never before been seen in the same place.

From 13 to 17 October, the Getty is also bringing together around 120 international scholars to see the exhibition and attend the 19th International Congress on Ancient Bronzes (a symposium that was launched in 1970), with a week of presentations on the field’s most pressing issues. Expect the Apoxyomenoi (on loan from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Croatian ministry of culture) to attract a lot of attention. Scholars will try to work out the relationship between the two works, as well as a head from the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, of the same style. All seem to have been cast from related moulds.

Apoxyomenoi (“the scrapers”) refers to the post-performance ritual of athletes, who would remove sweat and dirt from their skin with a strigil—a metal tool with a curved blade. The figures on show seem to be cleaning their strigils, but the tools themselves are missing. The Croatian athlete was found off the country’s coast in 1996 by a Belgian dentist on holiday.

The Getty’s head of antiquities, Jeffrey Spier, says new discoveries by fishermen and divers, as well as archaeologists, are driving scholarship. “A lot of statues have been found in the past 20 years, mostly from shipwrecks off the coast of Italy, Greece or Croatia.”

Two other recent discoveries on show include a head of a Macedonian, found by Greek fishermen in the 1990s, and a head of a Thracian king, discovered in Bulgaria in 2004. The growing sophistication of underwater research expeditions has helped to make the most of new finds.

The show’s co-curator Kenneth Lapatin says that there has been a boom in Hellenistic scholarship, long considered the ugly stepchild of classical studies. “It used to be seen as a period of degeneration after the high point of the Classical,” he says. “Today, Hellenistic works are getting a lot more attention… they are so vivid and realistic; people can relate to them.”

The exhibition has been organised with the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where it will travel next (13 December-20 March 2016).

Fakes and fusions: Getty experts on panels they are chairing at the symposium

Authenticity and forgery

Jeffrey Spier, head of antiquities

“A lot of forgeries were made in the 19th century and passed off to collectors, so they ended up in museums. Professor Mireille Lee of Vanderbilt University is talking about 19th-century fakes in Paris, including several in French museums. Now that they’re starting to analyse composition and technical features, we are starting to realise that there are more fakes than we thought.”

The Hellenistic East

Timothy Potts, Director

“Fifty years ago, Hellenisation in the wake of Alexander the Great was seen as a fairly simple process of the Greeks imposing their culture on that of the local communities they conquered. It’s becoming increasingly clear that there was a much more subtle blending of indigenous cultures with classical traditions. You get hybrids with clear elements of Greek culture but also native religions and ritual.”

Conservation and analysis

Jeff Maish, associate conservator

“These pieces have been buried for two or three thousand years, so they have been altered significantly by the burial environment, whether land or ocean. That can create conservation problems but also analytical problems: if the bronze has been altered and what you see today is not what was made originally, you have to be particularly careful making interpretations.”