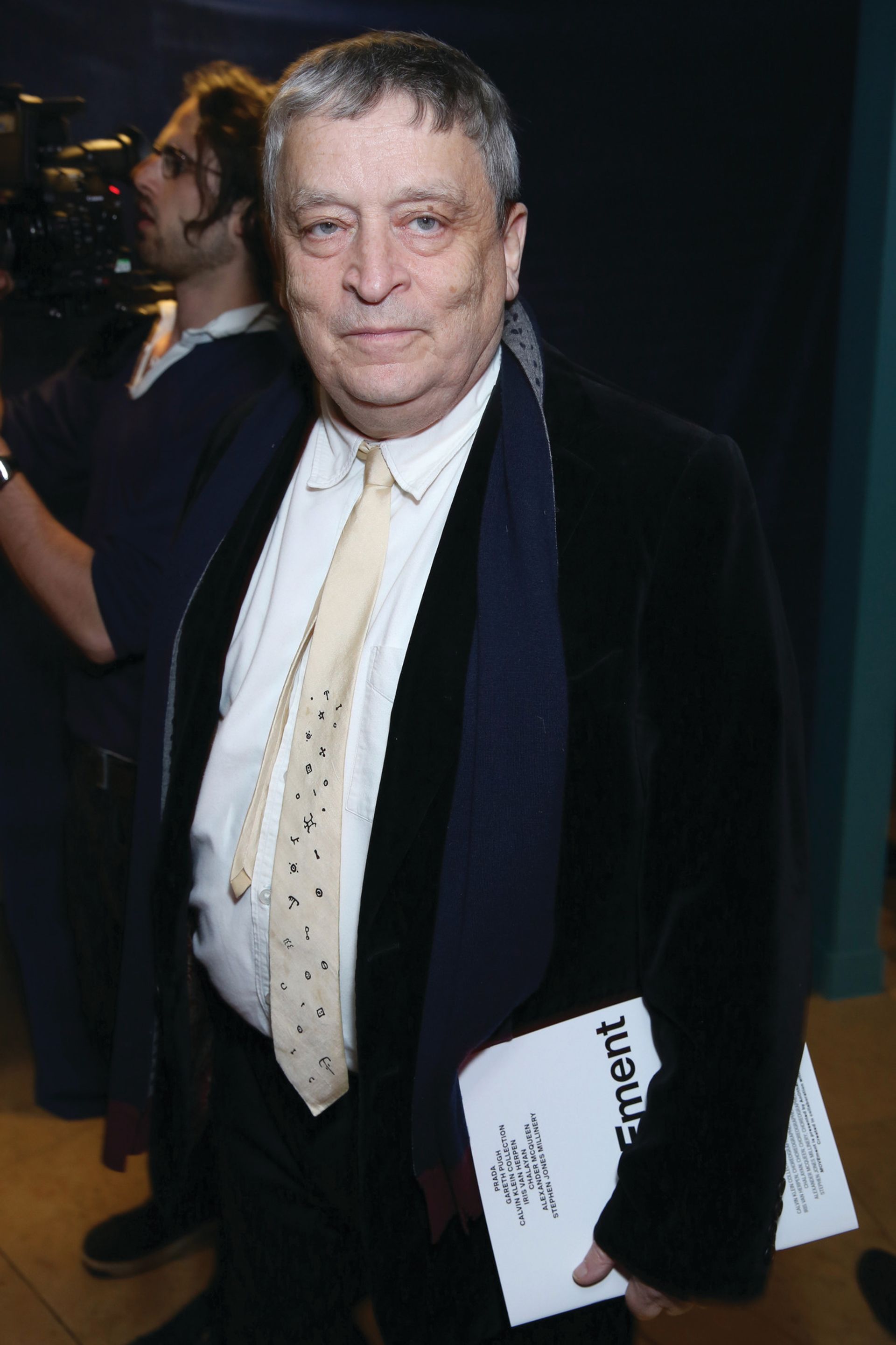

When the Frieze Masters art fair (14-18 October) opens in London later this month, it will make a big addition to its usual programme. The innovation at this year’s event is Collections, organised by Norman Rosenthal, which presents eight scholarly exhibitions representing ideas that could be expanded to grace the walls of public institutions. Each represents the collection and interests of an individual art dealer who is an expert in the field.

Rosenthal’s aim is to show that it is still possible, “with knowledge and love”, to put together outstanding collections of art from previous periods in history. But the former exhibitions secretary at London’s Royal Academy of Arts was also inspired by his sense that “the ideas for exhibitions are easy. The problem is turning them into reality.”

Rosenthal says that he has always wanted to mount an exhibition of wooden Egyptian sculpture. “It is a whole department of Egyptian art that no one has concentrated on. Everyone loves the mummies and the stone sculptures, yet what is left of wooden art is amazingly beautiful,” he says. At Frieze Masters, the Geneva-based gallery Sycomore Ancient Art will mount a display of such pieces—the germ of a show that might have been.

Small shows of Italian Maiolica and German Expressionist portrait heads also feature in Collections, again curated by dealers, whose importance in the world of art history Rosenthal wants to recognise. “They are a mechanism of cultural preservation,” he says. “If things have no value, they will be thrown away.”

The concept also reveals the fact that many exhibitions are just a notion in somebody’s head, prevented from blooming by factors beyond a curator’s control—and cost isn’t the only one. “Politics is the art of the possible. And exhibitions are political in many respects. I don’t think we could do the big Africa show that Tom Phillips and I did at the Royal Academy today, for example,” Rosenthal says, refusing to be drawn further. “It would be impossible to do an exhibition of ancient art from Syria at the moment. It’s all a question of timing.” Rosenthal reveals that he and Phillips have always wanted to stage a show about ornament.

With this in mind, we asked a number of leading figures from the art world about the shows that they dream of putting on—but so far have little hope of realising.

Dream on

Lars Nittve, executive director, M+ museum of visual culture, West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, Hong Kong

Dream exhibition: Walter De Maria retrospective

I tried for many years to mount a retrospective exhibition of the work of the American artist Walter De Maria, who died in 2013 and was a very good friend of mine. That sounds as if it could happen, but the first challenge is that some of his key works are situated in places from which you cannot move them, like The Lightning Field in New Mexico, the Vertical Earth Kilometer in Kassel, Germany, or the New York Earth Room in SoHo, New York.

How do you put together an exhibition where the works are spread across the world, yet an important aspect of them is that you should experience them physically? Let’s say you could figure that out, perhaps by travel plans or by linking them up on video, even if it wouldn’t be ideal. And people haven’t really seen the smaller works he made in the 1960s and 1970s, so there was the possibility of doing a smaller, gallery-based exhibition of those.

But then I came across the second obstacle. De Maria felt that a retrospective was an artistic death sentence. It was something he refused to think about doing, even though it would be very beneficial in understanding the full scope of his work, because he has remained the most important, undervalued artist of his time. He is one of those legendary artists who made works that people make pilgrimages to.

What he did was to stay outside all major movements from the 1960s onwards, while his work touched upon those movements in a very profound way. His works had a performance element, but were also Minimalist and conceptual. They are among the very few realised works of land art. Even Pop art is present because he was the drummer in the earliest incarnation of the Velvet Underground.

I don’t think there is a photograph of him after the mid-1970s. He avoided all types of publicity and interviews. He didn’t go to his own openings. So he did nothing to promote his work through his persona. That is why it would be important to shed more light on the work. It will remain my dream exhibition. Perhaps I can do it when I retire.

Xavier Bray, chief curator, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

Dream exhibition: The Baroque in Colonial Latin America

One of the great art-historical moments that is vastly underappreciated is colonial art in South America. Having worked on Spanish art for most of my life, I think it is like working in British art and suddenly discovering India—another side to Britain in terms of the great architecture and so on it left behind. The same goes for Mexico, Guatemala and South America in relation to the Spanish and Portuguese colonies.

In each of those countries are the remnants of the fact that religious orders were sent out by the Spanish and Portuguese kings to conquer people’s souls. In doing so, they had to replace what had been there, like Mayan or Incan culture, with Catholicism, not only adapting and understanding the indigenous religions, but using that—and the Jesuits were very good at this—to create Christian images. And so you get this amazing mix of iconography, where you have an Indian-looking Christ on the cross, or a famous Inca pilgrimage site changed into a place where the Virgin Mary has appeared, and then a whole cult grows around it.

Artists were sent out from Spain to train indigenous artists and that’s what I am interested in. They produced paintings, sculpture, architecture and amazing gilded altarpieces like the Mampara, Church de la Compañía in Quito, Ecuador. The reason this would be a very difficult show to pull off is that you would have to move a lot, and some of these places haven’t been touched. In central Brazil and Paraguay, there are several Jesuit seminaries with incredible altarpieces by indigenous artists. There’s this fantastic sculptor called O Aleijadinho, who made some highly expressive sculptures in disproportionate dimensions that reinforce their religious intensity.

I’m interested in the way in which all this local talent had to be controlled by the Catholic Church. But the exhibition would be impossible because South America is miles away. You could move the works, but they are very fragile and it would cost a lot of money. They have been in these churches since the 17th and 18th centuries and the change of climate would make it difficult. American museums have tried to do it, but they are a little closer. For a British public, this would be completely unknown territory. Perhaps I will have to go out there and make a documentary to rustle up interest.

Tim Knox, director, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Dream exhibition: The Orléans Collection

There was an exhibition at Houghton Hall recently that brought home Robert Walpole’s art collection, which was sold by his heirs to Catherine the Great in 1779. To see the paintings back on the walls was wonderful. I’d like to try to reassemble the collection of Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, which was sold in London during the French Revolution and bought by a consortium of English noblemen. He was guillotined while the sale was being negotiated.

The paintings have ended up in different galleries all over the world under different rules. Some are now in the US; a lot are in the National Gallery of Scotland. The National Gallery in London has the lion’s share, including its Titians, so that would be the obvious place to mount the exhibition. But the Fitzwilliam holds seven Orléans masterpieces that cannot be lent because of the wishes of the donor. So everything would have to come to Cambridge. It would be an amazing gallery of masterpieces again, transforming the way we see them. But I don’t think it will happen.

The other show I have always dreamed of doing, though I might bring this one off if I ever have time, is one about the English Civil War and its aftermath. It would contrast the extraordinary flowering of the arts under Charles I with what happened under Cromwell, who had strong links to the Cambridge area. It was a period of iconoclasm, but the new men who built houses such as Thorpe Hall and Wisbech Castle were influenced by Dutch fashions, and Cromwell reserved a lot of the best for himself, including work by Raphael and Mantegna, and occasionally commissioned masterpieces, such as his portrait by the miniaturist Samuel Cooper. It would be interesting to see the Caroline Camelot reimagined by the Puritans who followed.

Thomas Köhler, director, Berlinische Galerie

Dream exhibition: Anton von Werner and the art of the German emperor

This gallery exhibits the art made in Berlin, starting with the Secession movement at the end of the 19th century, which was made up of artists who were in opposition to the emperor’s taste. But the kind of art shown during the reign of the emperor after 1870 is ignored by art historians, so I would like to look at that.

One artist I am particularly interested in is Anton von Werner, who is known as a history painter because he painted these big retro-style paintings. But he did other things as well, including a series of great drawings. He is a fascinating figure because he was director of the Prussian Art Academy, but he was something of a dictator because he could control who was admitted to the school and in which style the painters were supposed to paint.

So the exhibition would raise questions of censorship and of what makes someone avant-garde, because Von Werner was very much influenced by photography, although he painted in a very conservative way. I would like to show paintings by him in which Modernism is represented; for example, there is a 1903 painting that was sponsored by a cosmetics company, showing the erection of a monument to Richard Wagner, also sponsored by the firm. That’s a very good example of the transition from a feudal society to a modern society dominated by the citizen, not the aristocracy.

Von Werner is only shown in Germany in history museums, never art museums. Art museums always concentrate on the avant-garde. So this would be a bit daring. It would also be controversial because he is considered a reactionary: he was against admitting women to art schools, he was a nationalist and he was the emperor’s favourite artist. These elements are tricky to talk about today. I would not aim to rehabilitate him, just to show different aspects of his work. But I worry about how the show would be received.

Lydia Yee, chief curator, Whitechapel Gallery, London

Dream exhibition: David Hammons and the 20th-century masters

This idea has been with me since I co-curated One Planet Under a Groove: Hip Hop in Contemporary Art for New York’s Bronx Museum of the Arts in 2001. Franklin Sirmans and I were speaking to the artist David Hammons and he said that what we should really do was cancel the show we were putting on and exhibit his work alongside 20th-century masterpieces by people like Francis Bacon, Marcel Duchamp and Jasper Johns. In the end, we were happy that he agreed to be part of the hip-hop exhibition, but quite often I think about his idea.

It would be an exciting exhibition to mount. Hammons works with found materials, often associated with black culture, and makes something new out of cast-off materials, such as a sculpture made from clippings from a barber’s. There is a big tradition in black culture of both sampling and call-and-response, responding to those who went before you, and I think that putting Hammons’s work in the context of those 20th-century masters would be fascinating. It would stir up a very interesting dialogue. For example, whereas Duchamp displayed ready-mades, Hammons appropriates things and alters them quite radically.

The reason this is a dream exhibition is the challenge of getting the loans from the estates of major artists. They wouldn’t necessarily know how Hammons would position their works and might be hesitant. He is not an artist who plays by the usual rules of the game, which is part of what makes him so important.

And then, of course, I would have to persuade him that he wants to do it. There would be a lot of persuasion needed all round. But I might try to give it another go.