The 2015 quincentenary of the birth of Lucas Cranach the Younger falls in the eighth year of the Luther Decade (2008-17), which in turn marks the quincentenary of the Reformation. Its theme is Bild und Botschaft (Image and Gospel), which is the subject of over a dozen exhibitions devoted to the elder and younger Cranach this year. Wege zu Cranach (Pathways to Cranach) provides a very good guide to the places with which the Cranachs were associated and Lucas Cranach: Hofmaler und Medienstratege (Court Painter and Media Strategist) is an excellent introductory overview of the “Cranach phenomenon”.

The three Thuringian exhibitions at Weimar, Eisenach and Gotha are devoted primarily to Cranach the Elder and his relationship with his patrons, the Electors of Saxony, to whom he remained loyal even after Elector Johann Friedrich was imprisoned and forfeited the electoral title in 1547 for his defiance in the face of Charles V’s attempts to reimpose Catholicism.

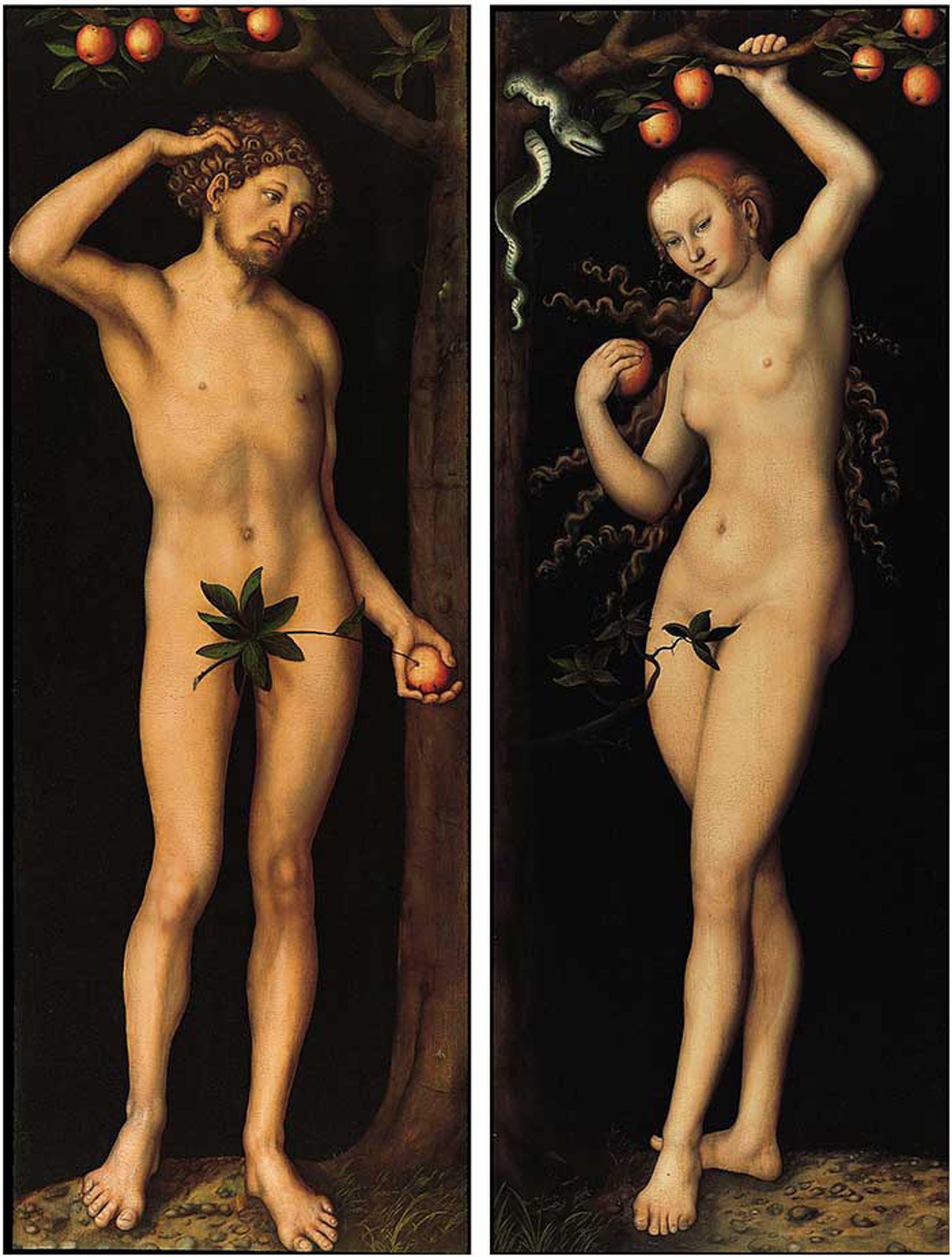

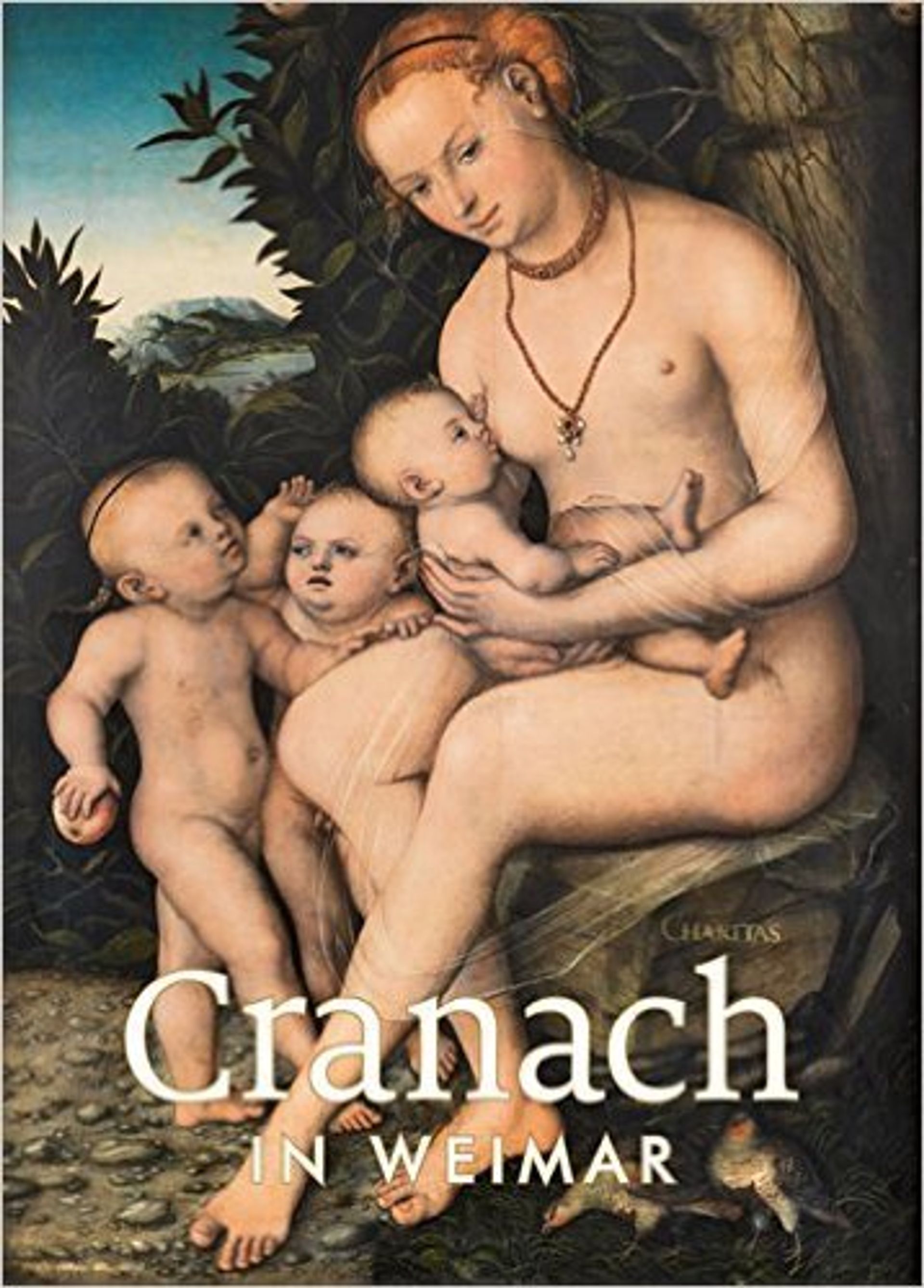

Cranach in Weimar, the catalogue of the exhibition in the Stiftung Weimarer Klassik’s Schiller Museum, traces Cranach’s progression from Wittenberg via Augsburg to Weimar. “Cranach’s princes” is devoted to work produced for the court and to Cranach’s paintings of both male and female nudes. These included the extraordinary Battle Between Naked Men and Their Complaining Women of 1527, in which he demonstrated his skill in the depiction of the most diverse bodily postures.

The disastrous consequences of Johann Friedrich’s defiance of Charles V are illustrated by Titian’s 1548 portrait of the defeated duke, the left side of his face clearly marked by the wound he had received at the Battle of Mühlberg the previous year.

The Weimar catalogue also explores the reception of Cranach’s work from the 18th to the 20th centuries. Cranach was highly valued from the outset but he was rediscovered in the later 18th century. Goethe, himself a descendent of Cranach, collected drawings by him. In the early 19th century, on the occasion of the tercentenary of the Reformation in 1817, the newly created Grand Duchy of Weimar remembered the role that the forebears of its rulers had played and memorialised Luther as a national figure using the images of Cranach.

There were some surprising resonances in the 20th century. A fascinating section documents the use of Cranach images in student drawing exercises at the Bauhaus school founded in Weimar in 1919. The Bauhaus preoccupation with woodcuts was directly inspired by Cranach and his school. The catalogue also draws attention to the fact that Hitler venerated Cranach as a truly German genius. On his 50th birthday he received the gift of Venus and Cupid the Honey Thief from the people of Thuringia. This version disappeared in 1945.

Portraiture and propaganda

Cranach, Luther und die Bildnisse (Cranach, Luther and the Portraits), the catalogue of the Eisenach exhibition, focuses on the Cranach Luther portraits and their reception since the 16th century. It details the techniques of quality control the Cranachs used in the production of their images. A trace outline of Luther’s face marked with ink was used to ensure that the image remained constant and that the message was accurate. The images were rapidly translated from one medium into another and marketed. The Cranachs never failed to respond to a political or commercial opportunity. They painted marvellous naturalistic portraits of Luther but they were also masters of image management and brand control.

The catalogue follows the accepted chronology of portrait types. Cranach the Elder first produced a print of Luther as an Augustinian monk in 1520: a serious-minded, sensitive young man. The second image shows him wearing his doctor’s hat. The third depicts him in disguise as Junker Jörg (Lord George), without scholarly or ecclesiastical dress. Then we have the moving portraits of Luther and his wife: images of an ordinary couple, suffused with a quiet dignity, designed to scotch Catholic rumours that Luther had married a monstrous harlot.

By the late 1520s, Luther had become the church father, and his image at this stage served as the archetype for the portraits of other reformers such as Philip Melanchthon. Characteristically, they show their subjects wearing the biretta, a symbol of ecclesiastical authority. The older Luther was generally portrayed bareheaded, as a professor in plain academic dress enhanced by a fur collar. The last image is that of Luther on his deathbed, which was disseminated as a print within days of Luther’s death.

The concluding section devoted to reception shows that, apart from studies by Barlach and Corinth, later images are undistinguished. The most modern portraits are garish and flat.

Scholarly survey

Bild und Botschaft (Image and Gospel), the Gotha catalogue, produced in collaboration with the Galerie Alte Meister at Kassel, is a superb hardbound quarto volume, which far surpasses the small-format paperbacks available at Weimar and Eisenach. It will be essential reading for scholars interested in the world of the Cranachs.

It starts by surveying Cranach’s pre-Reformation work for Frederick the Wise. This included altarpieces and, at a more popular level, woodcuts illustrating the elector’s collection of relics, the largest in the Holy Roman Empire.

The next section devoted to Reformation propaganda illustrates a radical change of style and demonstrates how rapidly Cranach mastered the new print media. Catholic printmakers filled their woodcuts with explanatory text. Cranach and his collaborators, by contrast, soon dispensed with text and simplified the images.

After the upheaval of the Peasants’ War of 1525, Cranach supplied the images when Luther advised princes and city councils on the restoration of order and the regulation of the affairs of their churches. The most important was the motif of Gesetz und Gnade (Law and Grace) illuminating the difference between Catholic damnation and Protestant salvation, which first appeared in 1528.

Biblical illustrations

Soon the new Protestant churches needed fresh illustrations for the old Biblical stories. Again, Cranach and his workshop obliged. New interpretations of Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery, Suffer the Little Children to Come unto Me, and Christ as Man of Sorrows underlined the significance of the New Testament, naturally in Luther’s translation, as a guidebook to the Christian life.

But Cranach still had to supply the needs of the court. Recreational subjects included Venus and Cupid the Honey Thief (1530, from the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen) The Silver Age: Quarrel of the Wild Men and Maternal Solicitude (1527-35), or the charming Resting Nymph of the Spring (1533). Paintings and prints of hunts and tournaments documented the life of the court, while official portraits, both of members of the ruling family and of key allies such as Landgrave Philip (“the Magnanimous”) of Hessen, served obvious political purposes.

The final two sections illustrate Cranach’s war propaganda in support of Johann Friedrich’s struggle against Charles V. A woodcut depicts the journey of the Protestants since the early 1520s as the flight of the Israelites through the Red Sea. A painting of around 1530 shows the head of John the Baptist on a platter. In 1538 Friedrich was shown in the company of the Wittenberg Reformers. Woodcuts of 1547, at the height of the military confrontation with imperial forces, depict him as the defender of the Protestant faith.

Even in defeat, images served a vital purpose. Portraits showing Friedrich’s prominent facial injury aroused sympathy for the captive elector. In 1552 Cranach the Younger went so far as to portray him as a Christian martyr: seated at a table wearing a biretta and holding a book, opposite a crucifix, his prominent left-side wound juxtaposed to that on Christ’s right side.

Altarpiece triumph

There could be no more fitting tribute to Cranach the Elder’s significance than his son’s 1555 altarpiece in the Weimar church of St Peter and Paul. It encapsulates the entire programme of the Cranach workshop. The panels to the left and right depict Frederick the Wise, his family and successors. In the centre, Christ on the Cross dominates a typical “law and grace” picture, flanked by the condemnation of sinners on the left and the glorification of the virtuous on the right. The latter feature three figures: St John the Baptist, Cranach the Elder, and Luther showing his printed Bible to the viewer. Cranach’s precedence over Luther is underlined by the stream of blood that flows from Christ’s side and lands on Cranach the Elder’s head. The image, it suggests, was more powerful than the word in the dissemination of the new faith.

This image is analysed in great depth in Bild und Bekenntnis, which also contains excellent scholarly discussions of other aspects of the history of the Cranach workshop and its reception to the 20th century. Those wanting just one book should buy the Gotha catalogue Bild und Botschaft. It is one of the highlights of the Cranach year.

Joachim Whaley is the Professor of German History and Thought at the University of Cambridge, a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College and of the British Academy. He is the author of Germany and the Holy Roman Empire 1493-1806 (2012).

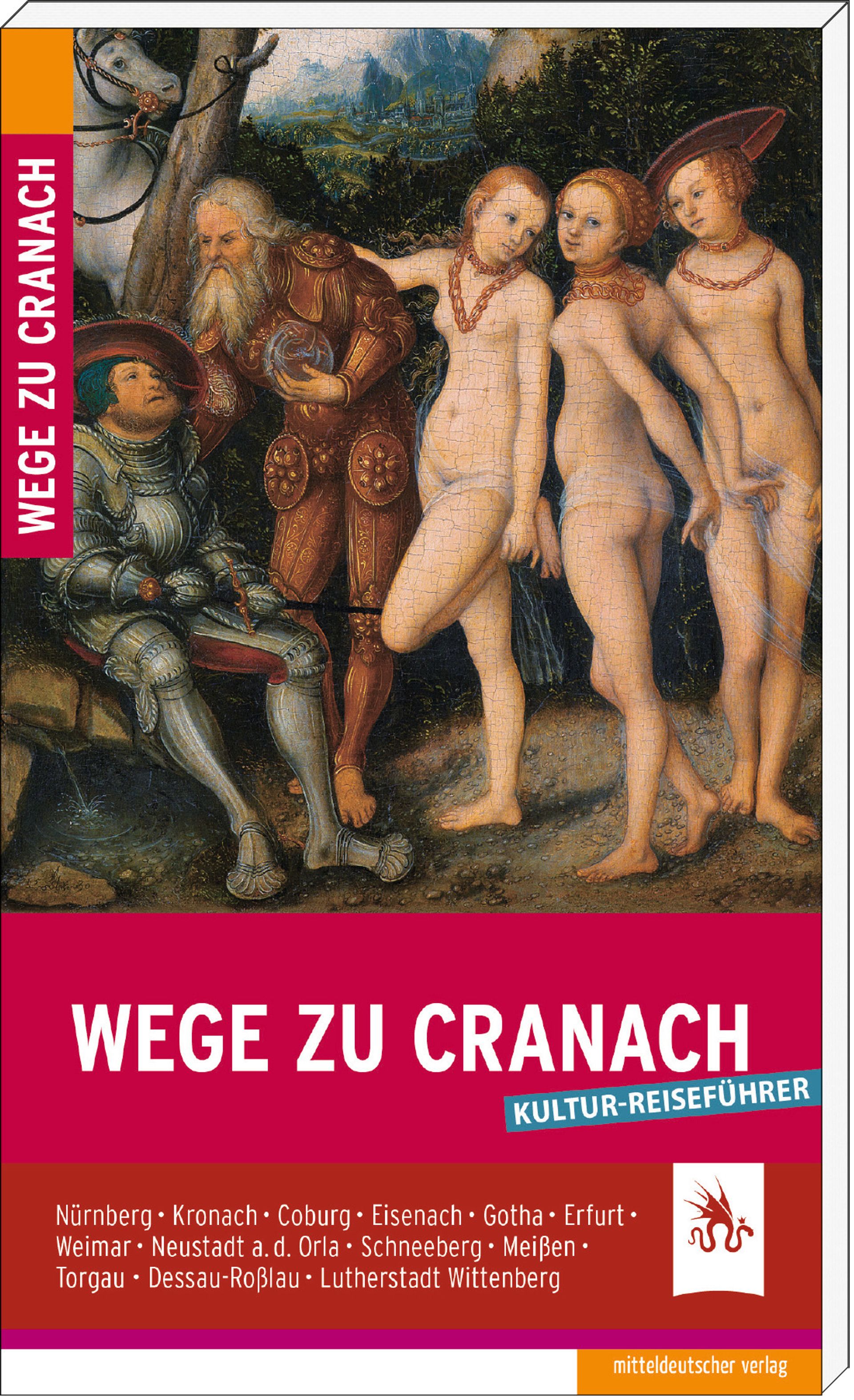

Wege zu Cranach. Ein Kulturreiseführer

Roland Krischke

Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 144pp, €9.95 (pb)

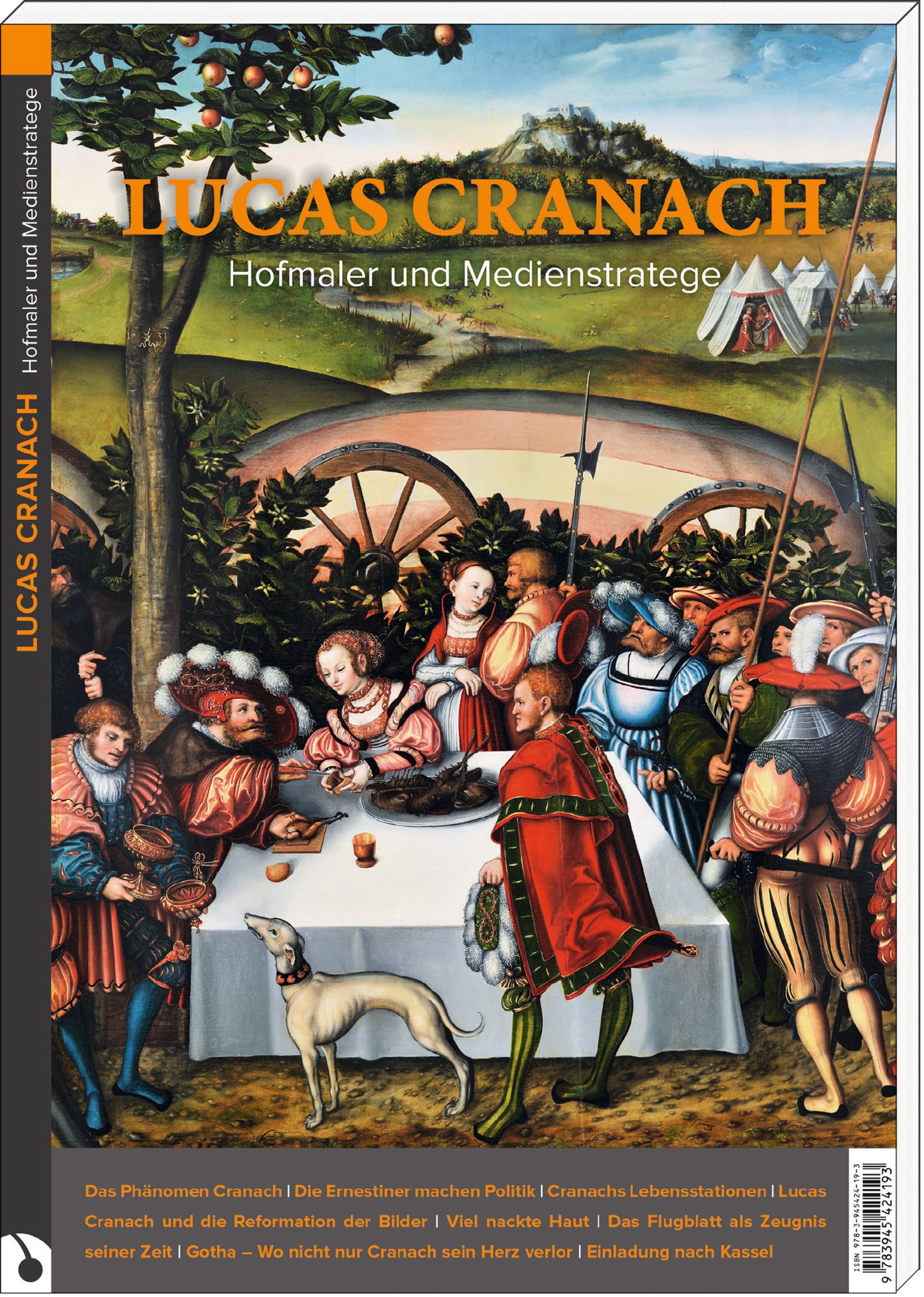

Lucas Cranach: Hofmaler und Medienstratege

Roland Krischke and Carola Schüren, eds

Morio-Verlag, 80pp, €9.80 (pb)

Cranach in Weimar

Wolfgang Holler and Karin Kolb, eds

Sandstein Kommunikation, 216pp, €14 (pb)

Cranach, Luther und die Bildnisse

Günter Schuchardt, ed

Schnell & Steiner, 208pp, €12.95 (pb)

Bild und Botschaft. Cranach im Dienst von Hof und Reformation

Edited by Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein Gotha and Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel

Morio-Verlag, 366pp, €24.95 (hb)

Bild und Bekenntnis. Die Cranach-Werkstatt in Weimar

Franziska Bomski, Hellmut Th. Seemann and Thorsten Valk, eds

Wallstein Verlag, 404pp, €28 (hb)

All volumes in German only