Decades after his anonymous Beijing graffiti protest propelled him onto the international stage, Zhang Dali has his very first museum retrospective in China. From Reality to Extreme Reality—The Road of Zhang Dali (18 September-18 March) charts the Zhang’s prolific career since 1987, but rather than open in Beijing, where he helped establish the city’s contemporary art scene, or the artist’s hometown of Harbin, the show is hosted by the Wuhan United Art Museum.

“It’s not like you just pick a museum, you have to know the people and be on the same page,” Zhang says. “This museum happens to be in Wuhan.” Opened by the Guanggu United Group in October 2014, the museum is among the projects meant to make the capital of Hubei province a cultural destination. The city also hosts a design biennale, the Taikang Insurance-backed Wanlin Art Museum opened there this year, and the Colin Chinnery-helmed Wuhan Art Terminus is due to launch in 2016.

“In Beijing, I couldn’t show in the National Art Museum of China, and the 798 museums are too small. Provincial museums provide an opportunity.” The artist adds that the current retrospective grew out of his participating in three earlier group shows at the Wuhan museum and a visit by the director Huang Liting to the artist’s studio the Heiqiao art district in Beijing.

Provincial cities like Wuhan also might provide more freedom from official intervention. “Places [in the South] like Guangzhou are more open,” observes Zhang. “Northern China is more conservative, and bigger cities have more government scrutiny on the art scene. China is changing, but to us artists it is too slow, we would like to have no censorship.”

Zhang is a seasoned veteran when it comes to navigating state censorship. “I’ve been censored a lot, from my very first show in May 1987, in Beijing’s Sun Yat-sen Park, which was up for three days then closed,” he recalls, “It hurt a lot. I’ve since gotten used it.”

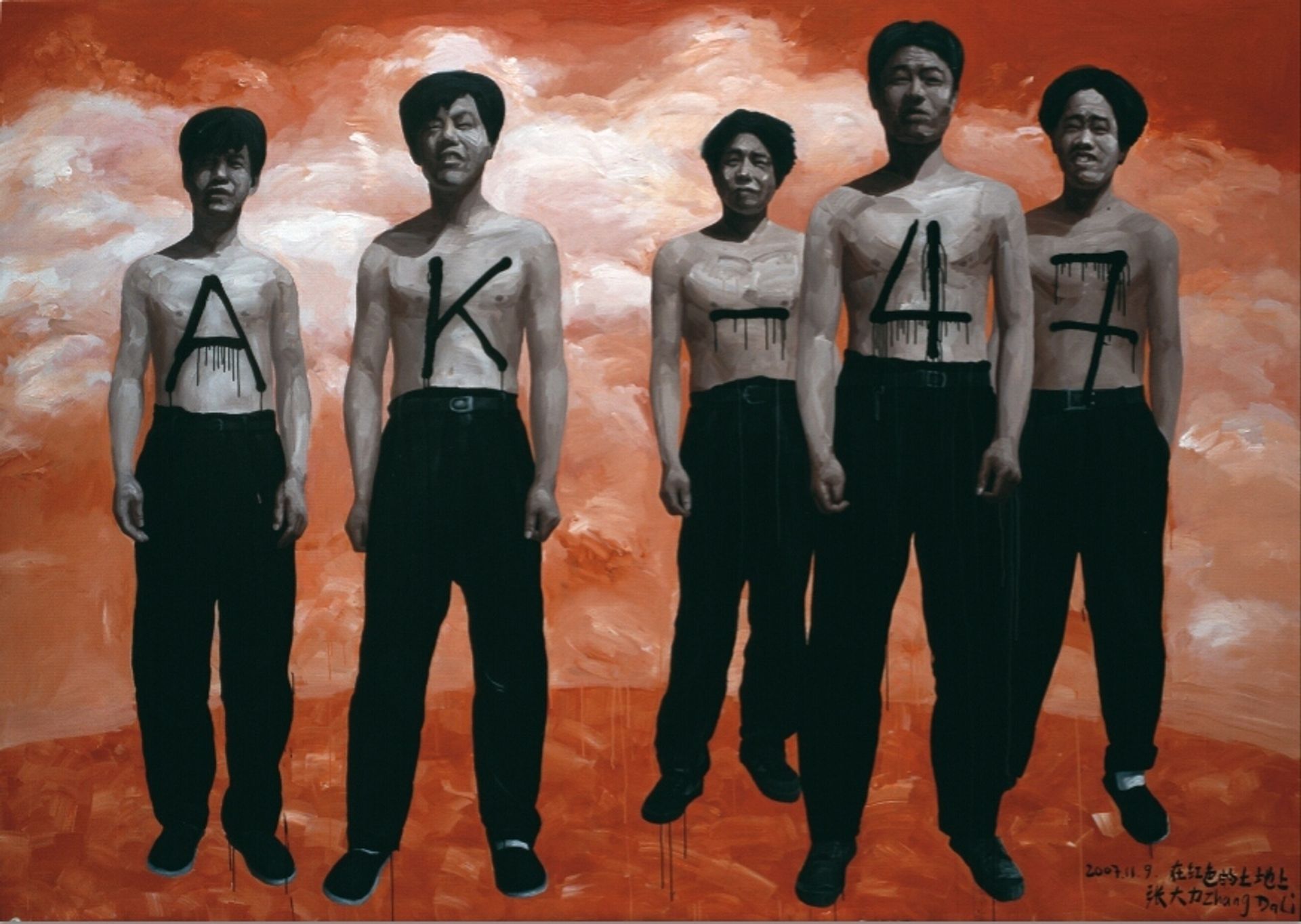

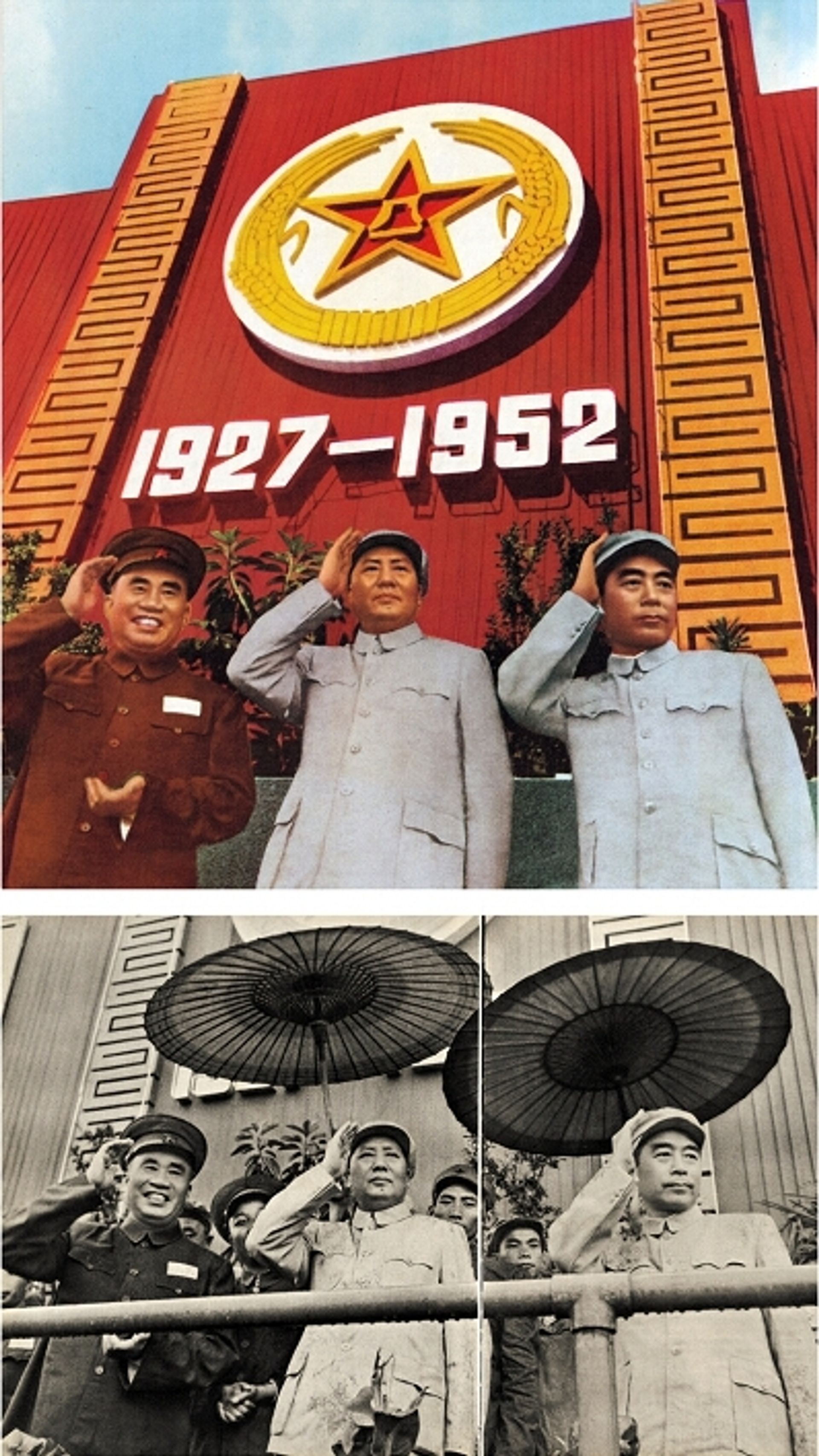

In the 1990s, he created graffiti under the pseudonym AK47 lamenting the demolition of ancient Beijing by drawing outlines or carving images of his own bald head onto condemned Hutong walls. His series Chinese Offspring in the 2000s, grotesquely realistic sculptures of migrant laborers often dangling from the ceiling like hanged men, expanded his focus on the human condition in Chinese cities. His paintings that superimpose government slogans on top of Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen Square imagery and his Second History project that presents doctored propaganda photos next to their originals has hardly endeared him to officials, prompting yet more shuttered exhibitions. But he continues to show in China frequently, albeit carefully.

“In China, you can criticise the government at home, but don’t do it in Tiananmen Square, or generally in public,” Zhang says. “A lot of artists, writers, poets create things for themselves, but don’t circulate them publicly. That you can do.”