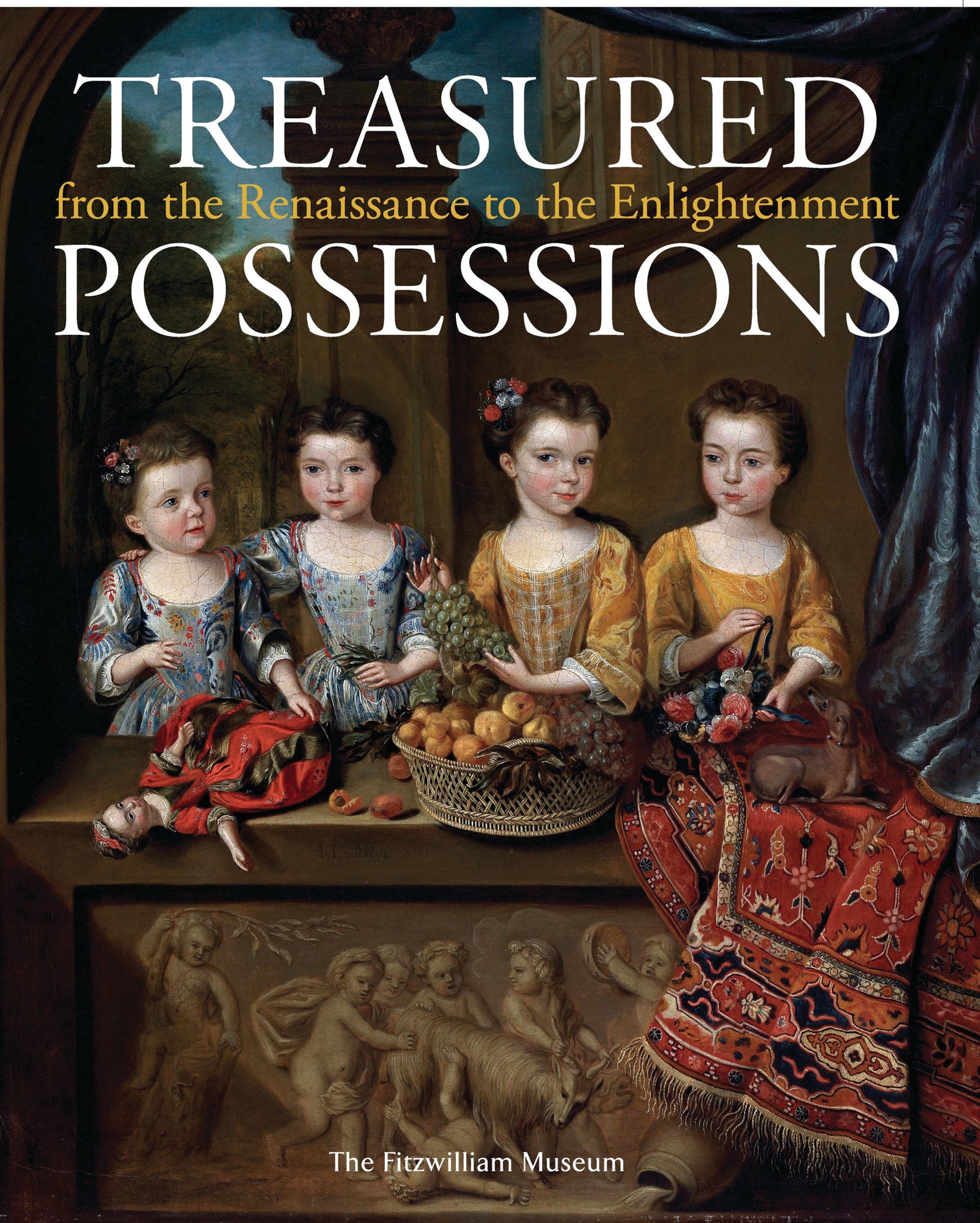

Treasured Possessions from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, edited by Victoria Avery, Melissa Calaresu and Mary Laven, accompanies an exhibition of the same name that is on at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge until 6 September.

Four main themes emerge: buying, selling and the growth of the luxury trade between about 1490 and 1800; objects associated with alcohol, tobacco (especially snuff), tea, coffee and chocolate (referred to as “the irresistible”); fashionable accessories, ranging from men’s and women’s clothes and shoes to fans and pocket watches; and domestic items including writing and dining implements, religious objects, and those associated with birth and death, such as earthenware models of cradles, death masks and mourning rings.

By about 1700, the ever expanding luxury trade, particularly with the Far East and the New World, was seen as a necessity that enriched the economy. By the time of the Enlightenment, the relatively bare houses of the Renaissance had become full of possessions, although they were not yet being produced on an industrial scale. The main thing is that they should have been “treasured”.

What is billed as a book rather than an exhibition catalogue on the publisher’s website is a celebration of objects, and includes some of the less well-known ones in the Fitzwilliam collections. The text comes with a certain level of material culture jargon. Hearts might sink on reading that “interaction with objects promotes socialisation” or items are “decontextualised, taken from their original settings and re-contextualised as collector’s items”. But it is worth persevering. For example, it is interesting to note the differences between shopping habits in London and Venice: one Venetian ambassador observed in about 1600 that English women went out shopping unaccompanied, whereas Fynes Moryson was surprised that a noble Venetian paterfamilias would go on his own to market and carry provisions home “either in the sleeves of [his] gown or in a clean handkerchief”. Even allowing for poetic licence, Ben Jonson’s masque The Entertainment at Britain’s Burse (1609) indicates just how many Chinese imports were available in England at that time. London silversmiths often added silver-gilt mounts and covers to Chinese porcelain, and other exotic imports such as coconut cups and nautilus shells. The book also includes the observations in 1556 of Fernão Mendes Pinto, probably the first ever recorded by a European, on the use of chopsticks in Japan at a time when most Europeans still ate with their fingers.

The treasured possessions of the book’s title encompass a huge range of themes and objects. Treasured by their original owners, collectors and curators, they make for a fine display of intimate and covetable items.

James Yorke was a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum for 32 years before retiring in June 2010. He has lectured and published articles on furniture and historic houses. His books include English Furniture (1990), Portugal’s Silver Service: A Victory Gift to the Duke of Wellington (1992) in collaboration with Angela Delaforce and Jonathan Voak, and Lancaster House, London’s Greatest Town House (2001)

Treasured Possessions from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment

Victoria Avery, Melissa Calaresu and Mary Laven, eds

Philip Wilson Publishers, 290pp, £39.95 (hb)