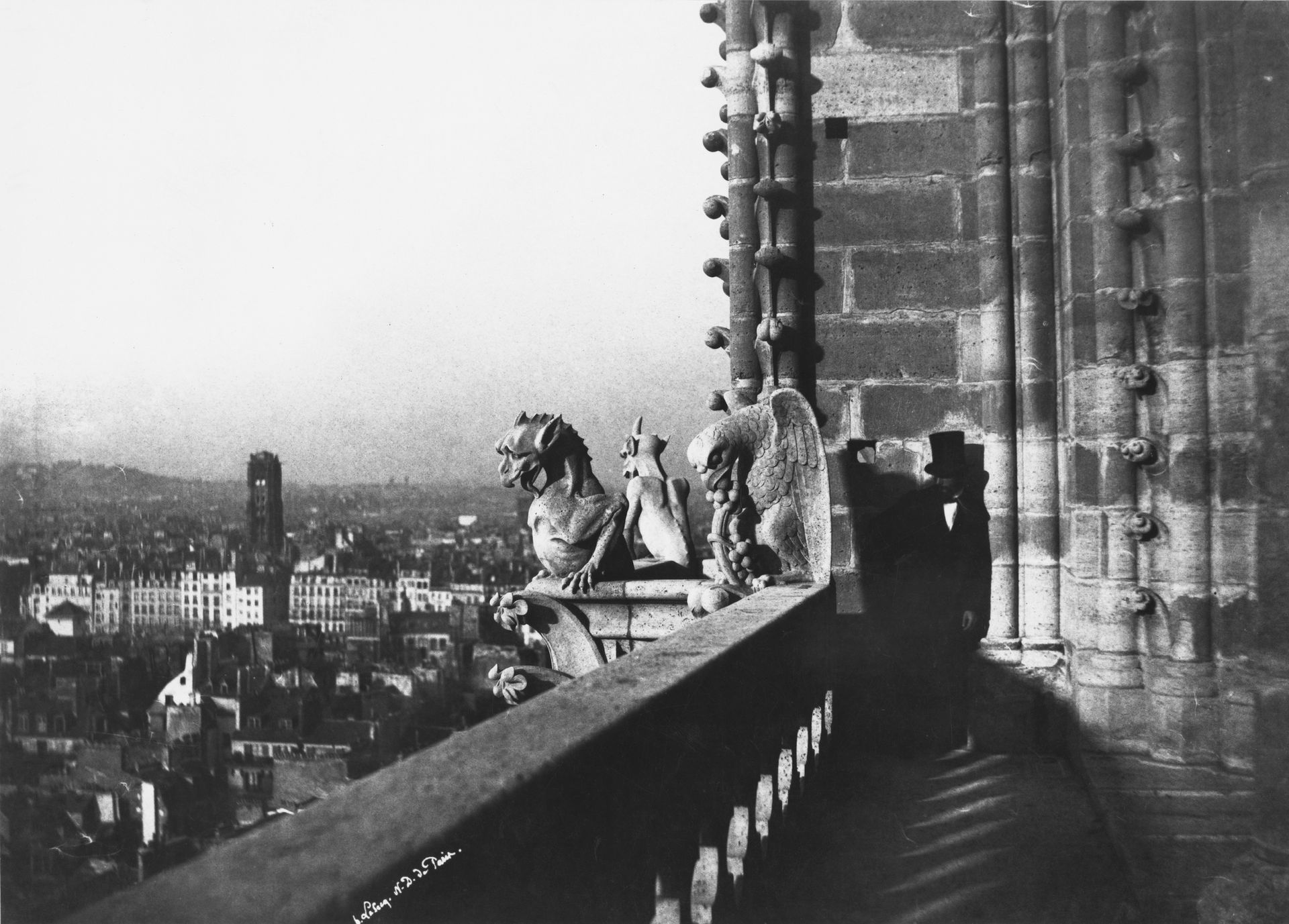

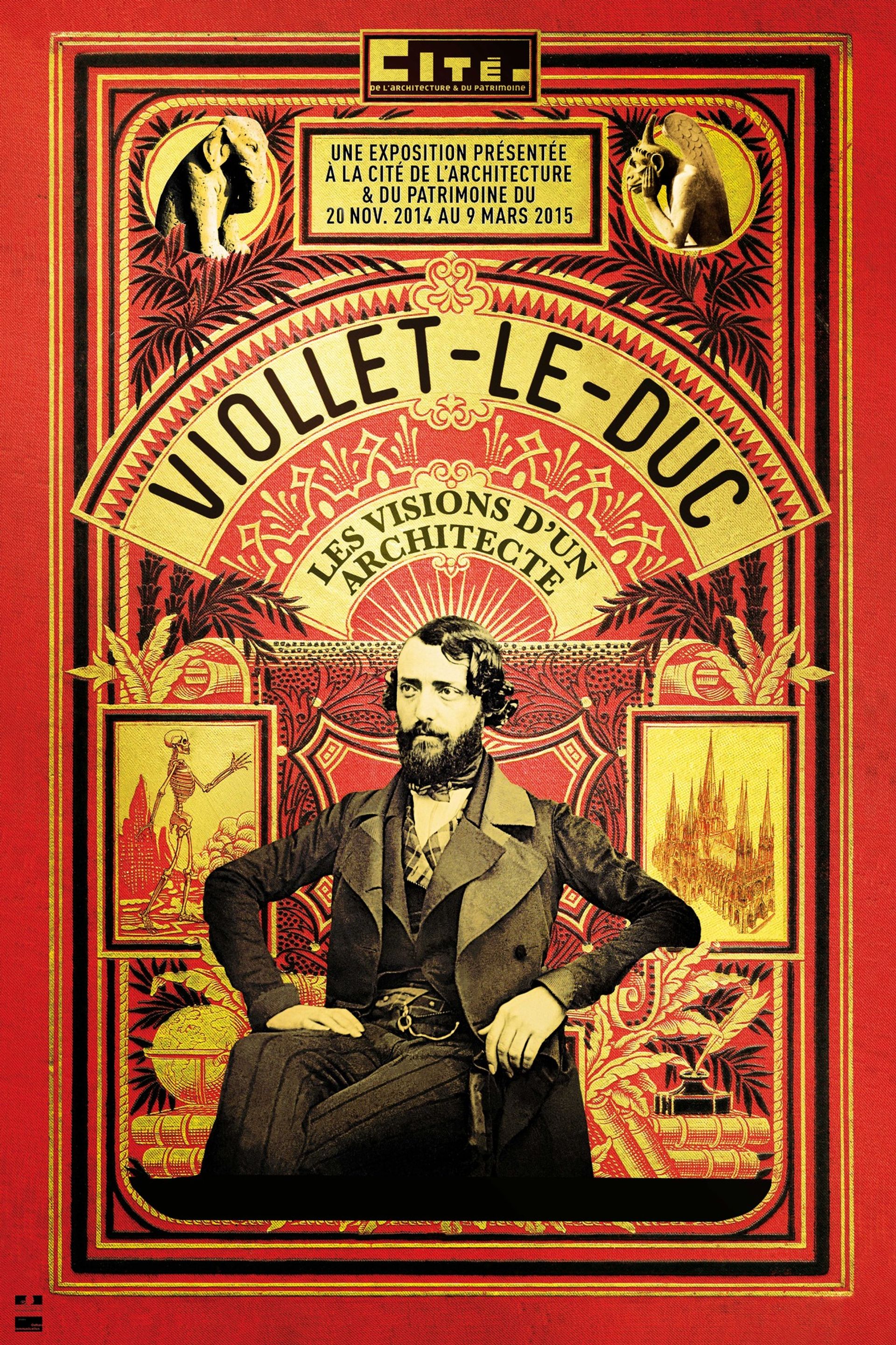

It has taken the French a long time to come to terms with Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879), the man responsible for the restoration of so many of France’s great medieval monuments, including Notre Dame in Paris, the Vézelay Abbey, the Cité de Carcassonne citadel and Château de Pierrefonds. In 1980, the centenary of his death was marked by a magnificent, wide-ranging exhibition at the Grand Palais under the direction of the historian Bruno Foucart. Last year, on the bicentenary of his birth, another exhibition at the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimonie again celebrated his work.

The catalogue for the latter show, Viollet-le-Duc: les Visions d’un Architecte, is lavishly produced, with a great number of illustrations, mostly in colour. A team of scholars provide 20 essays, followed by the catalogue of works shown. Viollet’s mastery of construction, whether in stone, brick, or (most remarkably) in iron, is well covered. The essays span a wide range, reflecting the extraordinary versatility of the man, who was not just a designer and restorer of buildings, but a mountain explorer, military engineer, watercolourist, journalist, politician and prolific writer (not just of the famous Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française, but also of enchanting books to introduce young people to architecture).

His remarkable personal magnetism won him a devoted band of assistants, whose works are discussed in authoritative essays. They include the sculptor Adolphe-Victor Geoffroy-Dechaume, the stained glass artist Alfred Gérente, the leadworker Louis-Joseph Durand, and the metalworker Placide Poussielgue-Rusand, whose astonishing great lectern from Notre Dame was one of the stars of the show. The lectern is no longer used in the cathedral, where—as Jean-Michel Leniaud points out—much of Viollet’s work has been dismantled or put away, or, in the case of his painted decoration of the apse chapels, allowed to decay. Even that is not so bad as what has happened at Toulouse, where most of his work on the Basilica of St. Sernin has been removed, or at the Basilica of St Denis, which has been gutted.

Also published this year is Martin Bressani’s Architecture and the Historical Imagination: Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, 1814-1879. This huge book (more than 500 pages) is not for the faint-hearted, but is based on an exhaustive knowledge both of Viollet’s work and of its artistic, literary and political background. It might be thought that he had a privileged upbringing, as his father was an official at the royal court, and his uncle Étienne Delécluze was an artist, and their salons were frequented by writers like Stendhal, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve and Prosper Mérimée. But for Viollet it was deeply unhappy, especially after the death of his mother in 1832, which left him at the mercy of what he called “this race of civilised reptiles”. This leads Bressani to see Viollet’s passion for the restoration of old buildings as psychologically motivated.

It is certainly welcome that today we can form a balanced view of Viollet’s achievements. For example, there is no doubt that much of the basilica of Vézelay would have collapsed without his intervention. His work at Notre Dame, undoing the destructive or incongruous efforts of previous centuries, was superb. We can now see Pierrefonds and Carcassonne as entrancing works of medieval recreation, with a strongly personal imprint which takes them way above the level of pastiche. The obvious comparison is with the work of William Burges. Like him, Viollet had a skill at designing buildings, objects, and patterns which was based on profound scholarship combined with imaginative fantasy. The illustrations in Visions d’un Architecte make this abundantly clear.

Viollet-le-Duc: les Visions d’un Architecte

Laurence de Finance and Jean-Michel Leniaud, eds

Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine in association with Éditions Norma, Paris, 240pp, €38 (hb); in French only

Architecture and the Historical Imagination: Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, 1814-1879

Martin Bressani

Ashgate, 624pp, £65 (hb)