The Science Museum is preparing for the launch next week of Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age, which the museum describes as “the greatest collection of Soviet spacecraft and artefacts ever shown outside of Russia”.

One of the key figures of the Soviet space programme in the 1950s and 1960s was Sergei Korolev (1907-1966). We spoke to his daughter Natalia Koroleva about the thrill of the Space Race and the background of some of the objects she has loaned to the London show.

You have lent a number of pieces to the exhibition. Can you describe some of your favorites?

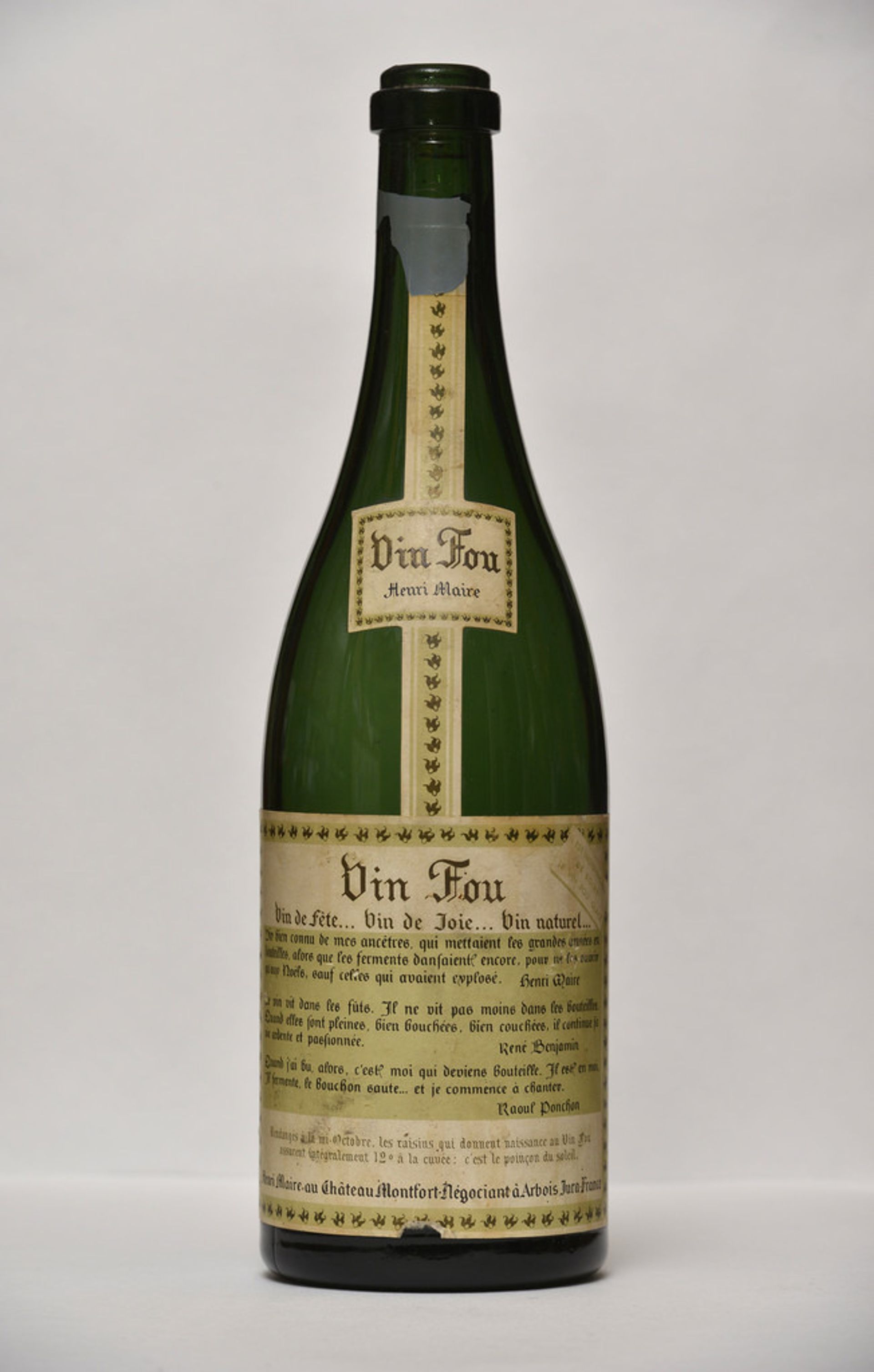

One of objects I have lent is a 1959 bottle of champagne, one of the 1,000 that the French winemaker Henri Maire lost in a bet. After the first artificial satellite Sputnik was launched, Maire made a bet with the Russian council that Sputnik will make it to space, but that nobody will ever be able to see the other side of the moon. So when the Luna 3 photograph appeared in all the newspapers on 4 October 1959, he sent 1,000 bottles to the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Also in the show, will be my father’s gloves, which he wore for a rocket launches at Kapustin Yar and Baikonur Cosmodrome [from where Sputnik 1, the world's first artificial satellite, and Vostok 1, the first manned spacecraft, were launched].

But the object that is very dear to me is a tin mug that has my father’s surname “Korolev” scratched into it with a nail. He used this mug in the Kolyma camp, a gulag where he was imprisoned for more than six years in 1938.

Your father was a key figure in a Space Race between the USSR and the US. Will this exhibition shed some overdue light on his achievements?

I think the aim of the exhibition is to give an overall impression of our country as a space pioneer. This is important because some foreign TV programmes forget that the first woman in space was Russian, not American, for example.

Few people know that my father, Sergey Korolev, and those who worked with him, made the Soviet Union’s space launches possible. In the Soviet Union, he was airbrushed out of the picture, which stopped him from receiving the Noble Prize twice.

When the Noble Prize Committee requested the name of the lead designer of the USSR's space technology, Nikita Khrushchev [the head of the Soviet Union at the time] said that that the main creator was the nation itself. My father remained in the shadow until his death in 1966 and the Noble prize wasn’t awarded to anyone for Russia’s achievements.

I am glad that the exhibition recognises my father’s legacy and that of those who worked with him.

How has the attitude to space exploration changed since the 1960s?

It has changed radically. It is no longer something extraordinary; it has just become an occupation for some. Back then, cosmonauts were heroes: they were greeted with flowers, fireworks and parades.

Nowadays space travel has become a common thing; many people go to space and spend a lot of time there. Recently, the Russian cosmonaut Gennady Padalka broke the record for the total time spent in space. He was there for more than two years.

• Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age, Science Museum, London, 18 September-13 March 2016