Dismaland, Weston-super-Mare (until 27 September)

Very much a Banksy-sceptic—especially since much of his work came in from the street to the art gallery—I approached his magnum opus Dismaland with distinctly less enthusiasm than my two young male companions, aged 13 and 23. But in its meticulous level of detail; its often outrageous splicing of mordant humour with deadly serious polemic; its overall ability to engage a demographic way beyond the art world with issues that have nothing to do with family fun; while at the same time managing to channel a strangely festive seaside spirit, Banksy’s “Bemusement Park” pulls it off. We had a genuinely grand day out whilst constantly being brought up short to grapple with the many unfunny and uncomfortable facts of our contemporary life.

Yes, there is the Instagram-friendly Cinderella carriage crash, the backwards-turning big wheel and the free David Shrigley bracelets handed out for failing to fell an anvil with a ping-pong ball. But there are also equally long lines for Guerilla Island with its Museum of Cruel Objects, including anti-homeless spikes and booby-trapped border fences; its geo-dome full of protest placards and banners; and its lively Comrades Advice Bureau full of multiple organisations specialising in campaigns, protests and direct action. There is no doubt that exiting the circus tent—featuring such crowd-pleasing exhibits as Damien Hirst’s unicorn or Ronit Baranga’s self-devouring dinner set—to be greeted by a pool floating with models of refugees aiming for the white cliffs of Dover, is an assault on good taste and notions of decency. But so too is the colossal tragedy which is taking place on coasts not too far from the golden sands of Weston-super-Mare.

Grayson Perry: Provincial Punk, Turner Contemporary, Margate (until 13 September)

With his frocks, pots and media friendly persona, Grayson Perry has now acquired official national treasure status. This excellent and extensive overview of all his modes of expression is a timely reminder of what an astonishingly versatile yet consistent artist he is. Whether in the incised detail of his multifarious ceramic works, the elaborate intricate design of massive tapestries or the meticulous mini-worlds of his etched maps, we see that Perry’s formidable skill as a draughtsman has been a crucial factor in his ability to simultaneously seduce and subvert. Comparing his sketchbooks from 1983-85 to those made just a few years ago reveals not only how his language has evolved but also confirms that his distinctive voice was already in place right from the beginning, as was his often overlooked mastery as a colourist. His often audacious but always pitch-perfect palette sings through his sketchbooks, across his pots and reaches an apotheosis in his textiles. Perry the provincial punk wears a finely wrought frock of many colours.

Rough Music, Cass Sculpture Foundation, Goodwood (until 8 November)

A significant outcome of the Cass Sculpture Foundation’s recent commitment to commissioning new work from younger artists has been the creation of an outdoor kiln, which this summer was used to make onsite pieces by ten of the UK’s leading contemporary artists working in ceramics. The resulting exhibition has been organised by Alex Hoda and Robert Rush, who have also contributed works, and presents a rich range of approaches, techniques and responses to a medium once restricted to the world of craft. The show’s title and overall theme refers to the 18th- and 19th-century English folk practice of subjecting miscreants to a cacophonous acting-out of their misdemeanour outside their own home. The various riffs on domesticity and absurdity range from 2013 Turner Prize winner Laure Prouvost’s saucy ceramic tabletop; Hoda and Rush’s playful puzzle jugs to Bedwyr Williams’s parade of pickle jars cast from his own head.

The Temptations of Pierre Molinier, Richard Saltoun Gallery, London (until 2 October)

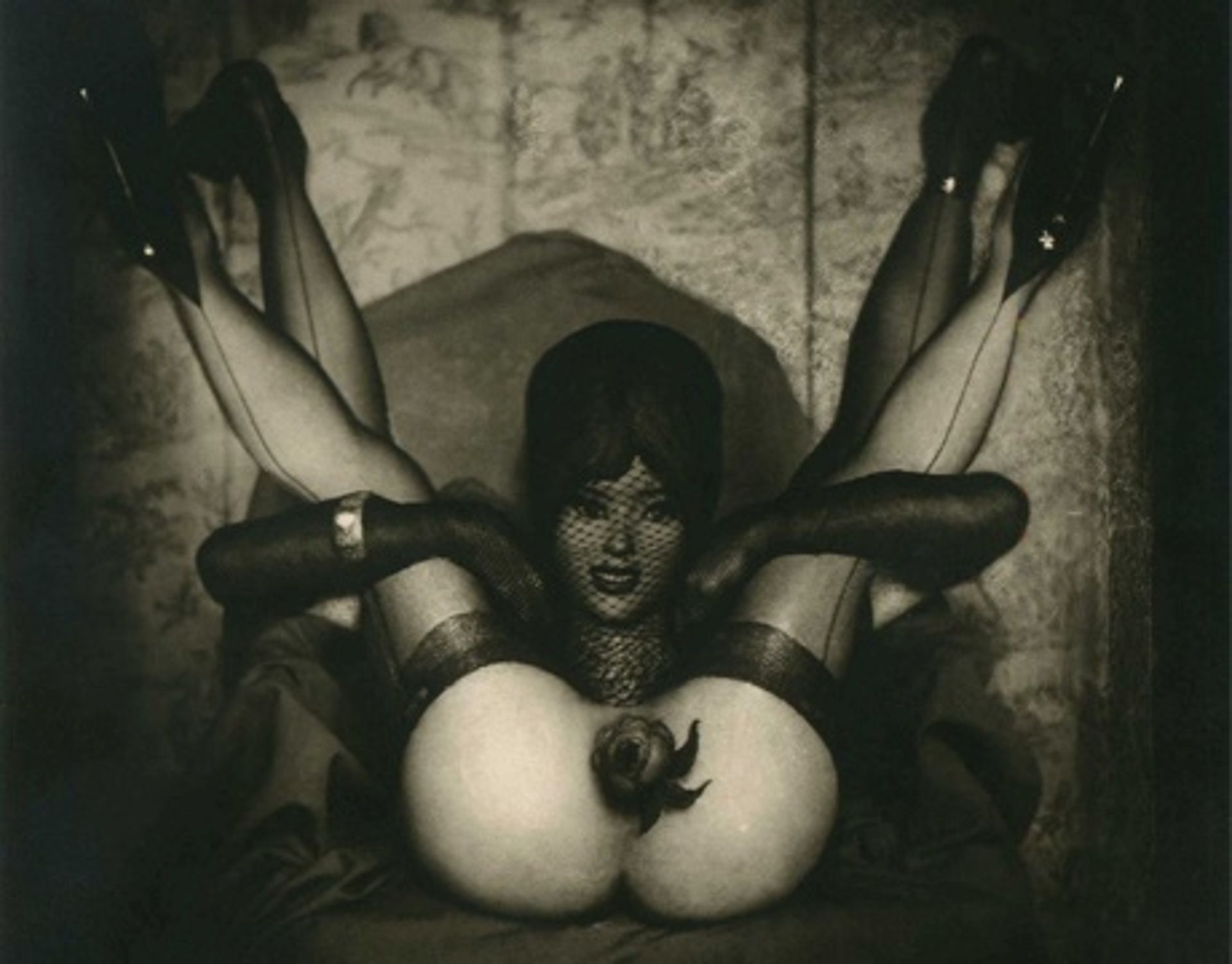

Pierre Molinier wanted people to be “contaminated” by his work. And the multitude of disquieting photographs that this onanistic housepainter, artist, transvestite and sometime Surrealist made from the 1930s onwards, are certainly staged in such a way that you feel less a viewer and more a prurient voyeur. But Molinier primarily intended his art to be “for my own stimulation” and in his small black and white silver gelatin prints he repeatedly appears, performing for himself and the camera whilst corseted, masked and sporting stockings and stilettoes. Sometimes he is impaled and self-fellating. And, when his face is seen, he invariably enacts all his perversions with a sinister rictus smile. Molinier also created elaborate photomontages of bizarre multi-limbed personages made up of numerous distorted versions of himself or the very few models with whom he worked. These hybrid creatures form evermore-elaborate extensions of his private fantasies and gender play. What Hans Bellmer and Salvador Dalí toyed with, Molinier lived: his life and his art were inseparable. It is this interlocking of fantasy and reality that charges his images with an intensity beyond the pornographic and which also led to his carefully stage-managed death. In 1976 Molinier shot himself in the mouth, but not before he carefully positioned a mirror so that he too could see it all. He also meticulously painted his toenails and left a note on the door.