During the past 30 years, Artemisia Gentileschi has been transformed from near obscurity to one of the best-known Baroque artists: the subject of novels and films, as well as a painter whose work has been explored in a number of serious academic publications. Most of these have tended to focus on the early and sensational events in her life and career. Discussions of her artistic output have concentrated on her early paintings, showing the impact of her contemporary, Caravaggio, or comparisons of her paintings with those of her father, Orazio. In Artemisia Gentileschi: the Language of Painting, Jesse Locker has chosen a different approach and instead discusses those aspects of Gentileschi’s life and work that have not received sufficient attention. She also highlights various possible misconceptions held about her over the last three decades.

The author pays particular attention to Gentileschi’s later, less familiar work following her arrival in Naples (probably in 1630) where, apart from a short period in England, she spent the remainder of her life. Just before this, however, Gentileschi spent a short period in Venice, although the exact extent of her stay there is not known. Locker shows, with a close analysis of the literary texts written to and about her by her Venetian contemporaries, that Gentileschi was a more active, significant and valuable participant in the artistic and cultural society of her day than has been realised.

There is much useful information concerning the literary and social society in Venice with which Gentileschi may have been connected. This elegant book is well illustrated, not only with Gentileschi’s work (particularly the lesser-known examples), but also with comparative examples by Venetian and Neapolitan artists, which enable the reader to comprehend straightaway the finer points of the author’s arguments. The impact of Veronese’s Esther before Ahasuerus (around 1570), for example, upon Gentileschi’s work of the same subject, and the influence of her work upon Francesco Solimena, among other Neapolitan painters, is made clear. Gentileschi’s paintings show her interest in contemporary Venetian theatre and the literary ideas discussed by members of societies such as the Accademia degli Incogniti. Members of these Venetian societies, like Gian Francesco Loredan or Antonino Collurafi, wrote nearly 20 poems and letters to her, exceeding those dedicated to other contemporary artists. Locker suggests that attitudes towards women in Venice, where women writers such as Lucrezia Marinella or Arcangela Tarabotti played a significant role, may have enabled Gentileschi to engage more fully in cultural debate with her contemporaries, concerning the nature and status of women, the questione della donna. This experience may have influenced the subject matter of her future work.

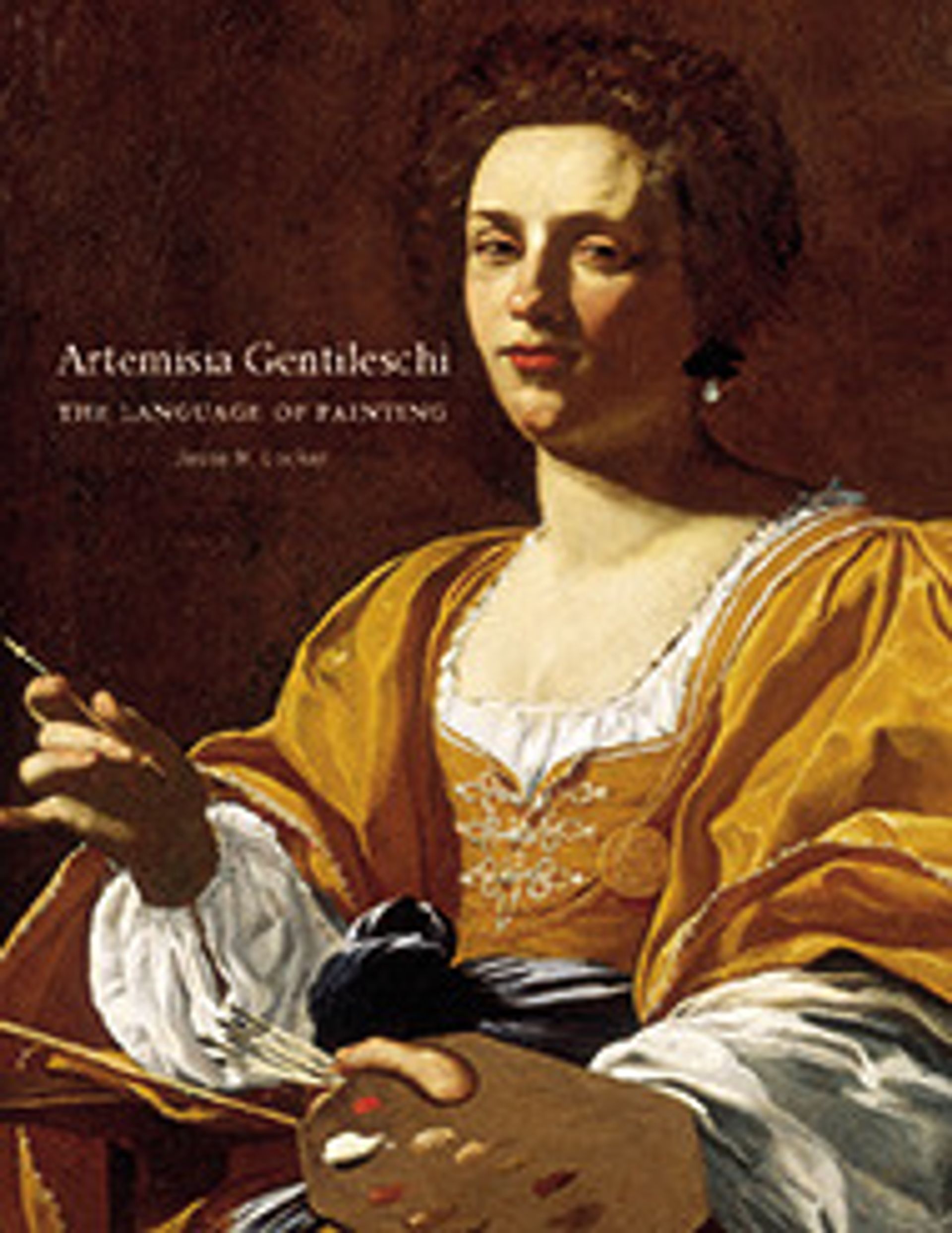

There is an interesting analysis of Gentileschi’s known and recently rediscovered self-portraits and the newly discovered portrait of her by Simon Vouet and the engraving by Jérôme David, as well as the above-mentioned letters and poems, which provide evidence that Gentileschi was already a respected and established artist by the time of her arrival in Venice and throughout the remainder of her career in Naples, where she is known to have advised the Viceroy, the Third Duke of Alcalá, on his painting purchases. It is likely that she already knew the duke in Rome from 1625, when he arrived as a Spanish ambassador to the papal court.

The extent to which Artemisia Gentileschi was forgotten after her death is also questioned. Most significant in this respect is the author’s rediscovery of an illuminating essay by Averardo de’ Medici, buried in the four-volume Memorie istoriche di opiu uomini illustri pisani, by various contributors and published in 1792. There is no doubt that Jesse Locker’s book is a welcome and rational addition to the literature on this leading 17th century artist.

Artemisia Gentileschi: the Language of Painting

Jesse M. Locker

Yale University Press, 236pp, $65 (hb)