The morning Gabriele Finaldi took over as director of London’s National Gallery, on 17 August, three-quarters of its rooms were closed to the public as warding staff went on indefinite strike at the height of the tourism season. The strike follows the gallery’s decision to outsource warding arrangements to a private company.

This leaves Finaldi and the gallery’s new chairwoman Hannah Rothschild with a crisis to resolve. At stake is their plan to modernise employment arrangements to extend opening hours and out-of-hours entertaining, which provides much needed funding. Government grant-in-aid has fallen by about 30% over the past five years. A gallery spokeswoman says the new arrangements will result in “considerable savings”.

Until last month, warding staff (known as gallery assistants) were employed on a variety of contracts. Some dated back decades, when evening events were unusual and overtime rates very high. Under the new system, staff can continue to choose whether to work out of hours. If there are insufficient volunteers, the outside contractor will provide additional staff.

War of words On 10 August the gallery outsourced its warding arrangements to Securitas, a Stockholm-headquartered company. The Public and Commercial Services Union, which represents many gallery staff, began a continuous strike the next day. Union members have held more than 50 single-day strikes this year, resulting in partial gallery closures.

A union spokesman says it is “a disgraceful use of public funds to set up what is in effect a strike-breaking force and usher in privatisation through the back door”. According to a gallery spokeswoman, the changes “are essential to enable us to deliver an enhanced service to our six million annual visitors”.

The institution’s five-year deal with Securitas is worth £40m. As part of the changes, management agreed from July to pay all staff at least the London Living Wage (£9.15 per hour), a voluntary minimum set by the Mayor of London.

A gallery statement stresses that “no members of staff will be made redundant” and all have “the option to move to Securitas with all the same terms and conditions”. The formal changeover of the 300 gallery assistants, half of whom are union members, will take months. It is unclear how many staff will leave or how Securitas will deal with strikers.

Political football Politicians are joining the escalating battle. Jeremy Corbyn, the hot favourite in the Labour leadership contest this month, criticised management “intransigence” and told us that Finaldi should “meet with the union and resolve this dispute”. However, the culture minister Ed Vaizey has backed the gallery’s “modernisation programme”.

A union spokesman wants Finaldi to resume negotiations. “We recently submitted an alternative plan to avoid privatisation, with proposals for new flexible contracts for existing staff,” he says.

New faces at the helm

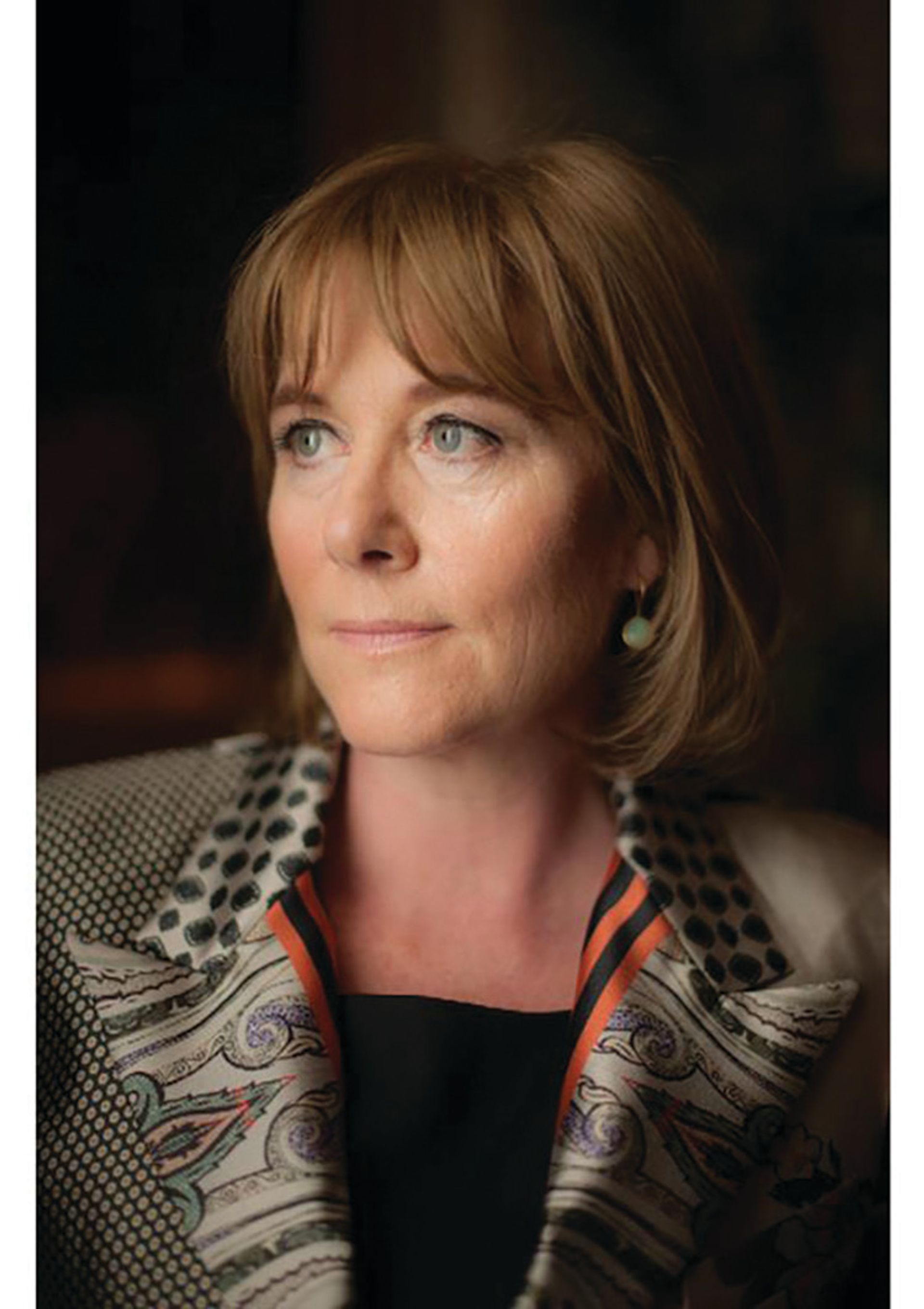

Hannah Rothschild, a writer and film-maker, took over as the National Gallery’s chairwoman from Mark Getty on 10 August. She has been a trustee since 2009. Her latest novel The Improbability of Love (2015) deals with the art trade. She is the daughter of Jacob Rothschild, who served as the National Gallery’s chairman in the 1980s and 90s.

Gabriele Finaldi took over as the National Gallery’s director on 17 August from Nicholas Penny. He had been the deputy director of collections and research at the Prado in Madrid. Born in London to Anglo-Italian parents, he knows the National Gallery well, having served as its curator of Italian and Spanish paintings from 1992 to 2002.