Joseph Cornell began constructing his signature “shadow boxes” of assorted seashells and film stills, compasses and clay pipes, maps and laboratory vials in the early 1930s, around the time that the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger formulated his famous thought experiment involving an imaginary box containing a flask of poison, a clump of uranium and a cat. Cornell and Schrödinger never met, and there is no reason to think they were influenced by each other's work, but the cultural coincidence of their curious contraptions is nevertheless intriguing. What motivated both was the desire to help audiences comprehend the mysteries that underlie existence. For Schrödinger, whose disquieting diorama was purely hypothetical, the arresting arrangement of incongruous ingredients was concocted to illustrate how two contradictory conditions (the cat is both alive and dead, all at once) can theoretically coincide. An enchanting retrospective of Cornell's work on display this summer in the Sackler Galleries of the Royal Academy of Arts in London (RA) reveals that the merging of seemingly opposing perspectives on being—science and religion, mathematics and magic—is likewise what makes Cornell's ingenious gadgetry tick.

The exhibition of around 80 works begins with a small untitled collage that Cornell created in the early 1930s in the home he shared with his widowed mother and his younger brother Robert, who suffered from cerebral palsy. Cornell’s only studio and place of residence during his entire 40-year career—an address he rarely failed to return to each evening—was 3708 Utopia Parkway in Flushing, Queens. Hidden somewhere in every great exhibition is a key to unlocking the imagination of the artist on display, and this small collage—a five-by-eight inch cut-and-paste gem—provides clues to cracking Cornell’s charm-encrypted code. At first glance, the work appears to depict nothing more than a seamstress’s cluttered work station. Look closer and we see that the artist has subtly intervened into the otherwise mundane scene by putting in the head of an oversized rosebud beside the Singer sewing machine, precisely where one might expect to find a garment needing repair.

If ever there was a manifesto-work announcing an artist’s aesthetic intentions, this is it. Central to the collage’s meaning is an echo of a famous quotation from 1869 by the French poet Isidore Lucien-Ducasse, the self-styled “Comte de Lautréamont,” who died at the age of 24. It is a phrase that expatriate Surrealists living in New York seized upon in the 1920s as a kind of motto for their vision: “beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella”. By inserting a rose in place of the umbrella, Cornell signals his distance from the temperament of the Surrealists (several of whom, including Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dali, he would later come to know). That thornless rose—for centuries a symbol of mysticism and martyrdom, innocence and sacrifice—was a quiet assertion: Cornell’s world was stitched together not by absurdity and clever whim, but by legends and romance. “While fervently admiring much of their work,” Cornell once explained, “I have never been an official Surrealist, and I believe that Surrealism has healthier possibilities than have been developed."

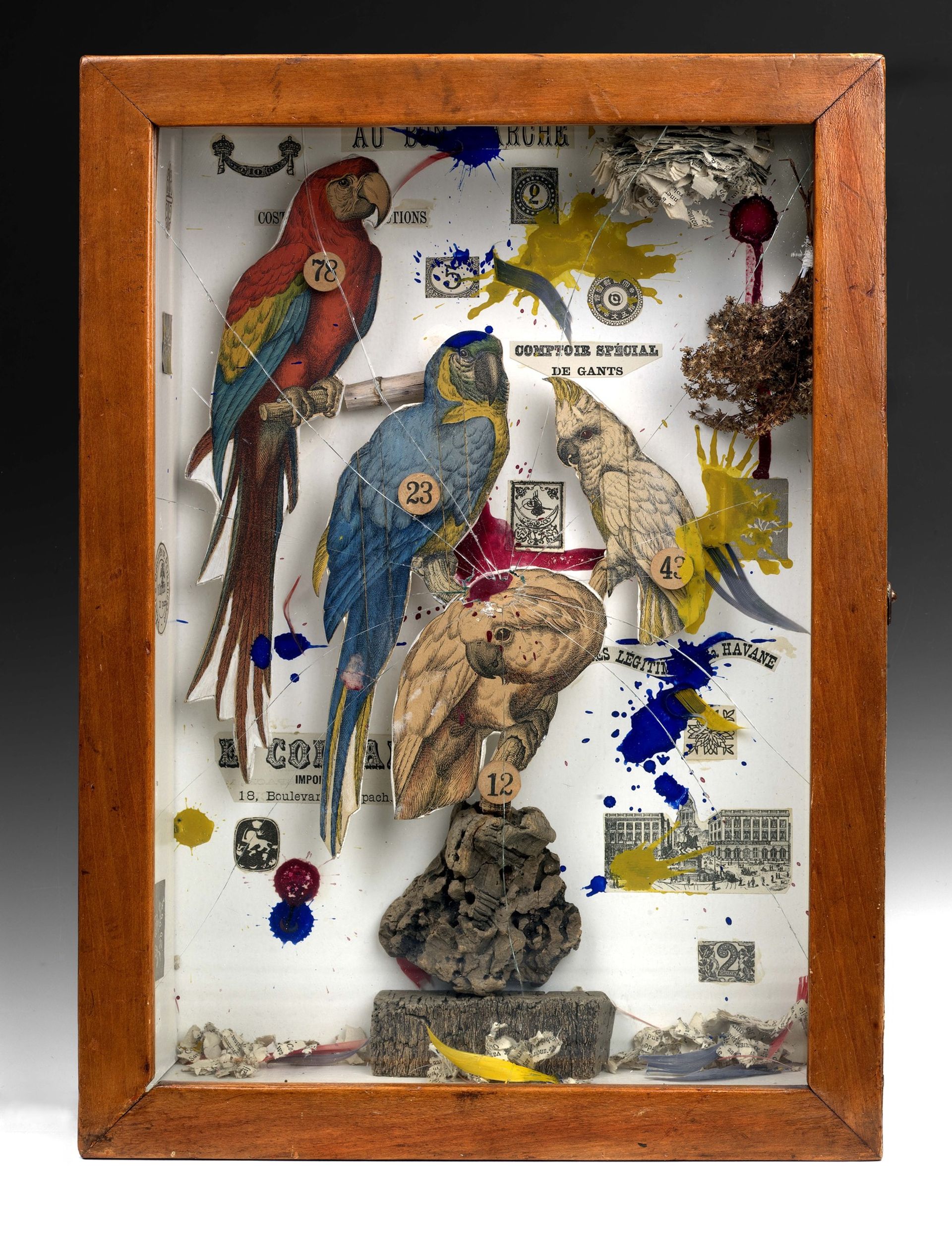

Amid the myriad minglings of metal thimbles and spray-painted twigs, magazine clippings and dried leaves, hunks of driftwood, rhinestones, painted lichen, watch-springs, corks, sherry glasses, mirrors, bells, crystals and sand, all carefully choreographed and re-choreographed into silent slot-machines of clinkety wonder, I found myself drawn most to those gizmos glued together by the artist’s innocent infatuations with starlets and unsuspecting ballerinas. Among the earliest of Cornell’s fully-fledged boxes is Untitled (M’lle Faretti) (1933), dedicated to one of the countless forgotten dancers, both contemporary and bygone, with whom Cornell was studiously obsessed. At the centre of the display is a souvenir postcard of a ballerina of the sort Cornell tirelessly collected while flaneuring New York’s secondhand shops. The dancer’s coquettish pose, sun-bleached into timelessness, is trapped behind an open mesh of brightly colored strings, plotting the girl’s faded existence against a ghostly grid that calls to mind the soulful geometries of Piet Mondrian (whom Cornell, years later, would befriend). Just above the central photograph is a row of hand-painted bouquet-like baubles (likewise trophies of the artist’s endless fossicks through the city’s bric-a-brac shops), that ambiguously suggest the flowers thrown on stage by admirers and those laid upon a loved one’s grave. The work at once lifts and lowers the curtain on life’s fleeting glories.

Although Cornell rarely travelled outside the New York area (and never further than the state of Maine), his boxes serve as calibrated time-machines, shuttling us back-and-forth between the impinging present of Depression-era America and those distant cultural pasts of which Cornell dreamt. Nowhere is such transport more poignantly engineered than in his portable museum L'Égypte de Mlle Cléo de Mérode cours élémentaire d'histoire naturelle (1940), perhaps the most famous of the works on display in the exhibition. Dedicated to Cléopatra Diane de Mérode (1875-1966), an aging French dancer of the Belle Époque who was once rumoured to have had an affair with King Leopold II of Belgium, the work rekindles her eclipsed celebrity. It provides the imagined ingredients of an alchemical experiment infusing Cléo’s material existence with that of her ancient Egyptian namesake. Made of an oak box fitted with a dozen cork-stoppered bottles (filled variously with plastic tokens and costume pearls, sequins and miniature photographs of camels), the eccentric kit is reminiscent of a child’s chemistry set and is a perfect example of the artist’s concurrent fascinations with history and healing, medicine and magic, playfulness and the profound. “Perhaps a definition of a box”, Cornell once reflected, “could be as a kind of ‘forgotten game’, a philosophical toy of the Victorian era, with poetic or magical 'moving parts', achieving even slight measure of this poetry or magic”.

Just as poets rely as much for their intensity and power on what is not said as what is, Cornell was acutely aware that boxes, as philosophical propositions, are capable of engrossing the attention of an observer by way of their concealments every bit as much as through what is revealed. Wandering the four rooms of the RA exhibition, one is frequently struck by how much the artist has hidden from the eye, tucked away in shut drawers, beneath tiny lids or under a gentle dusting of sand. The result is a body of work whose pulse feels suspensefully suspended (like Schrodinger’s cat) between what is there and what is imagined, what was and what is to be. Such tension can invigorate even the seemingly sparest of constructions, such as the relatively economic Untitled (Aviary with Parrot and Drawers), undertaken for the artist’s first solo exhibition at the Egon Gallery in 1949—a work emblematic of Cornell’s poetic approach. In the central recess of the box is a lithograph of a green and red parrot, perched in profile on a foreshortened branch. The imagined mechanics of a pair of watch-springs, spiralling behind its head, and the proximity of a chunk of real wood levitating beside the bird’s two-dimensional talons, invest the image with an urgency of imminent animation, as though the creature might suddenly flap into life. Surrounding the parrot are some thirty-four shut drawers, whose unknowable contents only amplifies the sense of mystery that Cornell has tucked deep into his secret cabinetry.

Kelly Grovier is a poet and art critic. His new survey, Art Since 1989, will be published in November as part of Thames & Hudson's World of Art series.

Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust, Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 27 September