There is a photograph by Diane Arbus that has always fascinated me. Entitled Westchester Family and taken in 1968, it is a well-known portrait of a well-heeled family at leisure. Supine on two chaise lounges in the foreground and clad in bathing suits, the handsome parents are separated by a small table and an emotional abyss, an estrangement so palpable that it dominates any reading of the image. A spacious lawn, empty except for a cropped swing set and picnic table and, further back, a seesaw and more seating, creates the ground of the picture, and moves toward a deep space blocked by trees that might mark the end of the family’s land. Between the parents, alone and bending over a small plastic swimming pool behind his mother, is a boy child, whose solitude and isolation scream to be noticed in spite of the tight though unbalanced composition of the picture. These three people might share the same space, but they seem to travel in orbits so separate that even their property and possessions cannot pull them together.

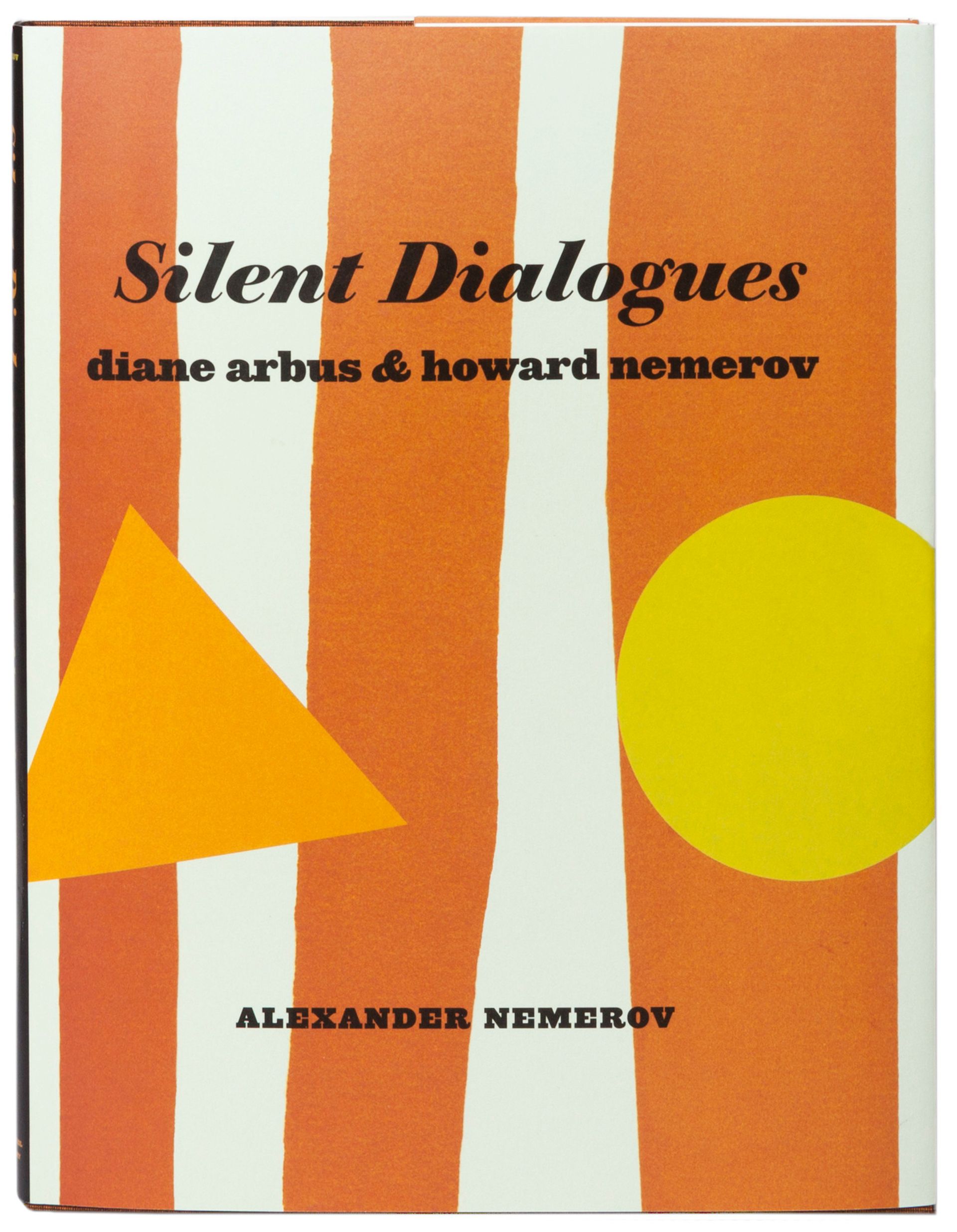

It is worth noting that the art historian Alexander Nemerov, in his new book Silent Dialogues: Diane Arbus and Howard Nemerov, never mentions this picture, though on some levels, it is the symbolic equivalent of what he does say: the “proverb” about family that has become “pictorial,” as he might phrase it. A greatly respected and beloved scholar, a Professor of Art History and American Culture at Stanford University, Nemerov is the son of the poet Howard Nemerov and the nephew of the photographer Diane Arbus—a legacy that, in fact, is the real subject of this beautiful book. Part memoir, part art historical analysis and part literary criticism, this slim and slippery volume makes clear that both art and life are “product[s] of relations rather than things.” Juxtaposing his aunt’s pictures with his father’s poems, teasing out themes and attitudes they do and do not have in common while telling tales of his own childhood, Nemerov attempts to suggest “the contours they share”—with each other and with him.

The book begins and ends with a statement: “I have no memories of Diane Arbus.” Alexander Nemerov was eight years old when his aunt committed suicide; he never met or talked to her. The same abyss that separated members of the Westchester Family clearly skewed the Nemerov siblings too, and in analysing poems and pictures, the author tries to figure out how, and perhaps why this was the case. This is, of course, an indirect way to bridge chasms of intimacy, but Nemerov makes clear in the book that this “form… of not knowing one another,” of referring to emotional issues only obliquely, was family tradition. Nemerov begins by describing his father’s hatred of photography, especially the “disgusting” version practiced by his sister; he then lists direct references to Arbus that show up in his father’s writings (there are only two). Circling back, however, Nemerov asserts that Howard did often refer indirectly in his various writings to the challenges Diane’s pictures presented to his sensiblity. Silent Dialogues is a compendium of these references, cross-references and correspondences, an attempt in retrospect to analyse a family relationship the author never experienced firsthand.

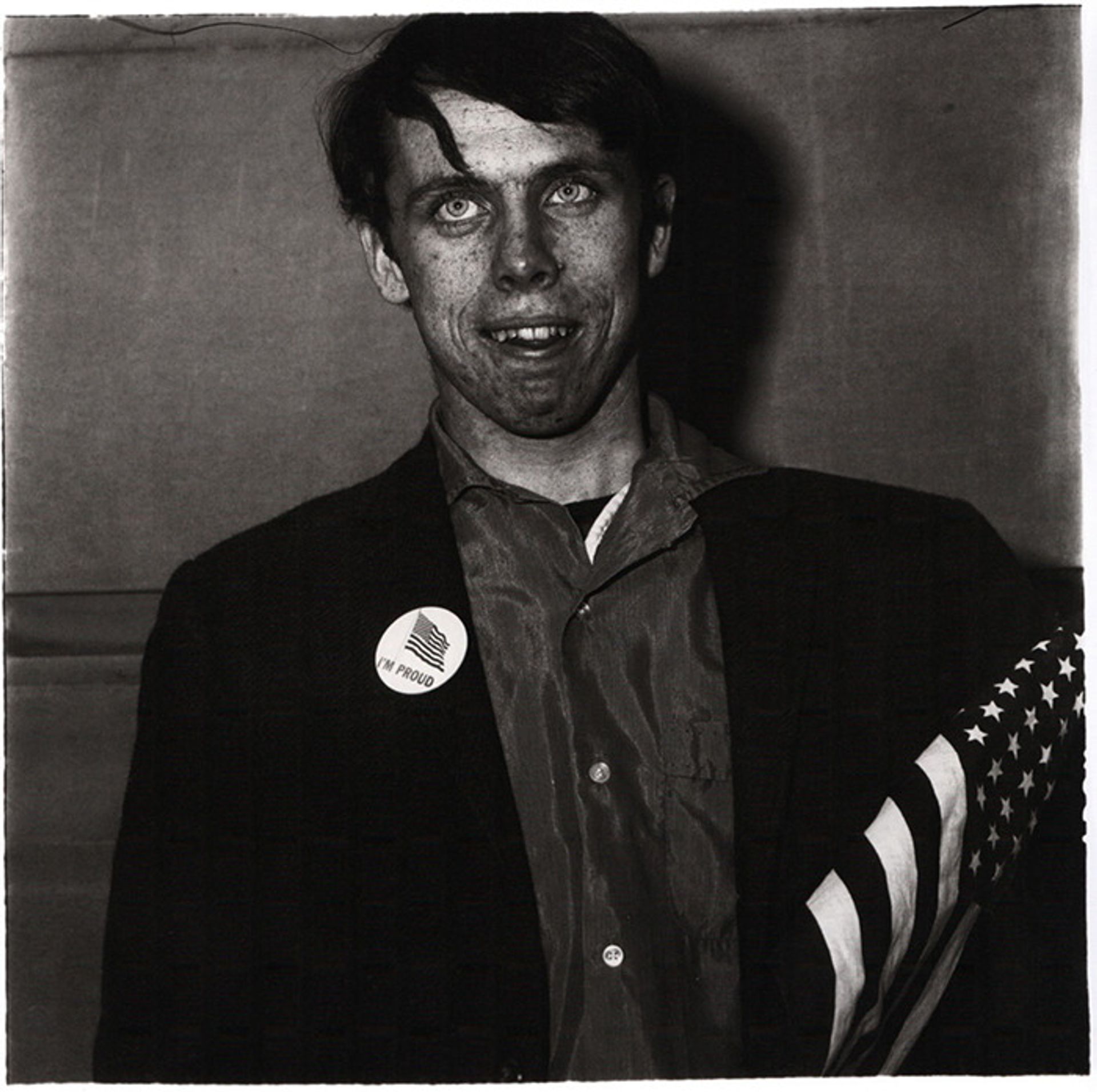

The book is comprised of two extended essays. The first, “A Resemblance,” focuses primarily on establishing the connections or disconnections between the two siblings, and Howard’s complicated relationship to Diane’s increasing fame. It is in this essay that Nemerov establishes the method that he will use throughout the book to develop his ideas. Diane’s photographs are juxtaposed with pictures of Howard’s books and published poems; occasionally works of art owned or loved by Nemerov’s family will enter into dialogue with that family’s own creations. There are times when this analytic strategy works brilliantly (when, for instance, he discusses Pieter Brueghel’s paintings in relation to poems by his father and photographs by his aunt), and other times when the need to find overarching themes seems a bit strained (his comparison of lawn motifs in their respective oeuvres is a case in point). But in all cases, Nemerov uses artistic expression as a means to establish a deep, if conflicted, spiritual connection between two siblings who had little physical contact during his boyhood.

The second essay is more narrowly focused on Arbus’ photographs, in particular those from the project she was working on right before her suicide in 1971. Entitled “The School,” the essay analyzes images from institutions for the mentally ill that comprise Diane’s last untitled series. These are incredibly strange and powerful pictures, and Nemerov’s discussion of them—and of Howard’s writings that complement them (or not) —is brilliant, visceral and especially mystical. Seen through Nemerov’s eyes, grassy fields reach into the afterlife, and mundane gestures transmute into fables.

A critical analysis morphs here, almost imperceptibly, into a meditation on the limits of knowledge, the role of language and the profound spiritual basis of both siblings’ attitudes toward art. The family lineage comes into play here, as Nemerov catalogs shared obsessions, like the siblings’ apocalyptic fantasies about the end of time—the only power and affirmation that could redeem the banality of the world of appearances for “minds born to see beyond what we usually see.” Using his father’s own criteria for genius, developed in his critical writings, Nemerov shows how Howard knew that his little sister had trumped him as an artist and how she had plunged deeper into their shared “religion of art” than Howard himself had dared. Using photography to reveal the secrets beyond language and thought, unflinchingly facing a world “relieved of the burden of having to be a mirror of her own intelligence,” Diane Arbus manifested an “ocean-infinite of feeling” that was difficult for Howard to confront.

Nemerov’s book is remarkable precisely because these analyses are simultaneously richly intellectual and deeply personal. They unite Roland Barthes’ studium and punctum in what can only be characterized as a journey toward self-awareness. At one point, Nemerov describes “the remorseless wish of these two people to get to the heart of things, down to essentials, to life itself, in a private dream of special closeness, like Franny and Zooey holding out for wisdom when plain old knowledge is always so cheaply on offer.” He concludes the paragraph with the following blunt statement: “It scares the shit out of me.” This book might be called Silent Dialogues: Diane Arbus and Howard Nemerov, but it is Alexander’s conversation too, his reckoning with a lineage he cannot escape. He may have no memories of Diane Arbus, but he is in thrall to her nonetheless.

Shelley Rice is an Arts Professor at New York University, with a joint appointment between the Department of Photography and Imaging and the Department of Art History.

Silent Dialogues: Diane Arbus and Howard Nemerov

Alexander Nemerov

Fraenkel Gallery, 106 pp, $29.95