Thomas Hirschhorn: In-Between, South London Gallery (until 13 September)

The more time you spend in Thomas Hirschhorn’s dramatic and provocative disruption of one of London’s most beautiful and versatile spaces, the more evident it becomes that both formally and conceptually this is not simply a theatrical mise en scène. Instead it is a thoughtful and multi-layered rumination on the meaning and nature of destruction and ruins. The sense of flamboyant chaos is in fact carefully considered and every detail meticulously planned. Even the myriad ways in which Hirschhorn’s signature brown packing tape is used—holding up, pinning down, fusing together, concealing, accentuating or unravelled and allowed to tangle and cluster—points to the precariousness of our interconnected world. And the challenges the artist faces in trying to create work that expresses this.

Also don’t miss two powerful films by Norwegian artist Ane Hjort Guttu upstairs, in her first solo UK show, which investigate the vexed relationship between education and creative freedom.

Nicholas Mangan: Ancient Lights, Chisenhale Gallery (until 30 August)

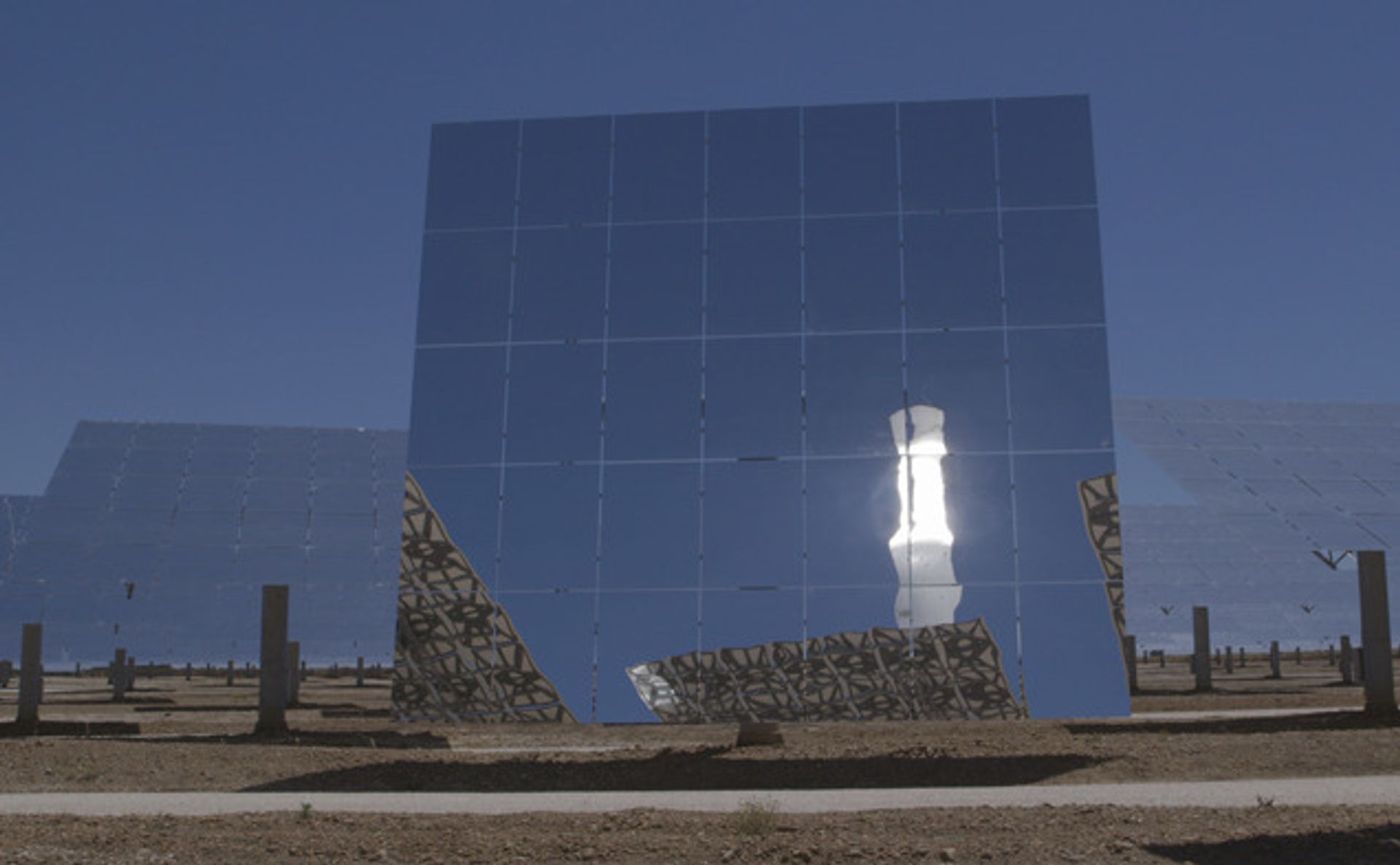

Systems and cycles—whether solar, economic or social—underpin Nicholas Mangan’s two-film installation, which is powered entirely by a special off-grid closed circuit where batteries in the gallery are fed by solar panels on the Chisenhale’s roof. Knowing of this energy source makes the first film of a perpetually but precariously spinning ten-peso coin (emblazoned with an image of the Aztec Sun Stone) appear all the more contingent and fragile, and especially appropriate to our current era of monetary turmoil. The second film presents various means of observing and monitoring the sun as well as its impact ranging from sunspots to tree rings. Both works owe their existence to one form of light being converted into another, and also to the fact that this has been an exceptionally sunny summer (no doubt due to global warming).

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, Victoria and Albert Museum (until 2 August)

People have been snooty about this exhibition—whingeing about the lack of documentary info and wall panels, and the privileging of sheer spectacle—but there is loads of verbiage in the catalogue. And I’m sure the man himself would have adored the opulent and unashamedly theatrical settings, lavishly provided by Gucci, Swarovski et al, which make the whole show a darkly kaleidoscopic experience. Whether baronial, boudoir, dungeon or wunderkammer, the procession of specially themed surroundings perfectly complement McQueen’s astonishing and audacious designs. They also enable you to get up close to the breathtaking detail of the subversive miracles that this maverick could perform with shells, feathers, leather and every conceivable form of fabric. Words are not necessary; you fill in with your own. There will not be his like again.

Aaron Angell: Grotwork, Studio Voltaire (until 30 August)

Who can resist an exhibition by an artist who runs a “radical and psychedelic ceramic workshop for artists”(a.k.a. Troy Town Art Pottery)? Or who cites influences ranging from the only magnolia-seed fossils ever found in England and Bram Stoker’s “awful final novel”, The Lair of the White Worm, to the Cherhill White Horse landmark (which apparently for many years owed its single glass eye to the artist’s 19th century ancestor Farmer Angell)? Suffice to say that Aaron Angell’s largest commission to date does not disappoint and that his arcane sources and his multifarious media—pottery, appliqué, embroidery, sheet metal, mouldy white sliced bread, flecked paintings on glass—all mesh together to form a bizarre but also cohesive and compellingly ritualistic whole.

Soundscapes: Listening to Paintings, The National Gallery (until 6 September)

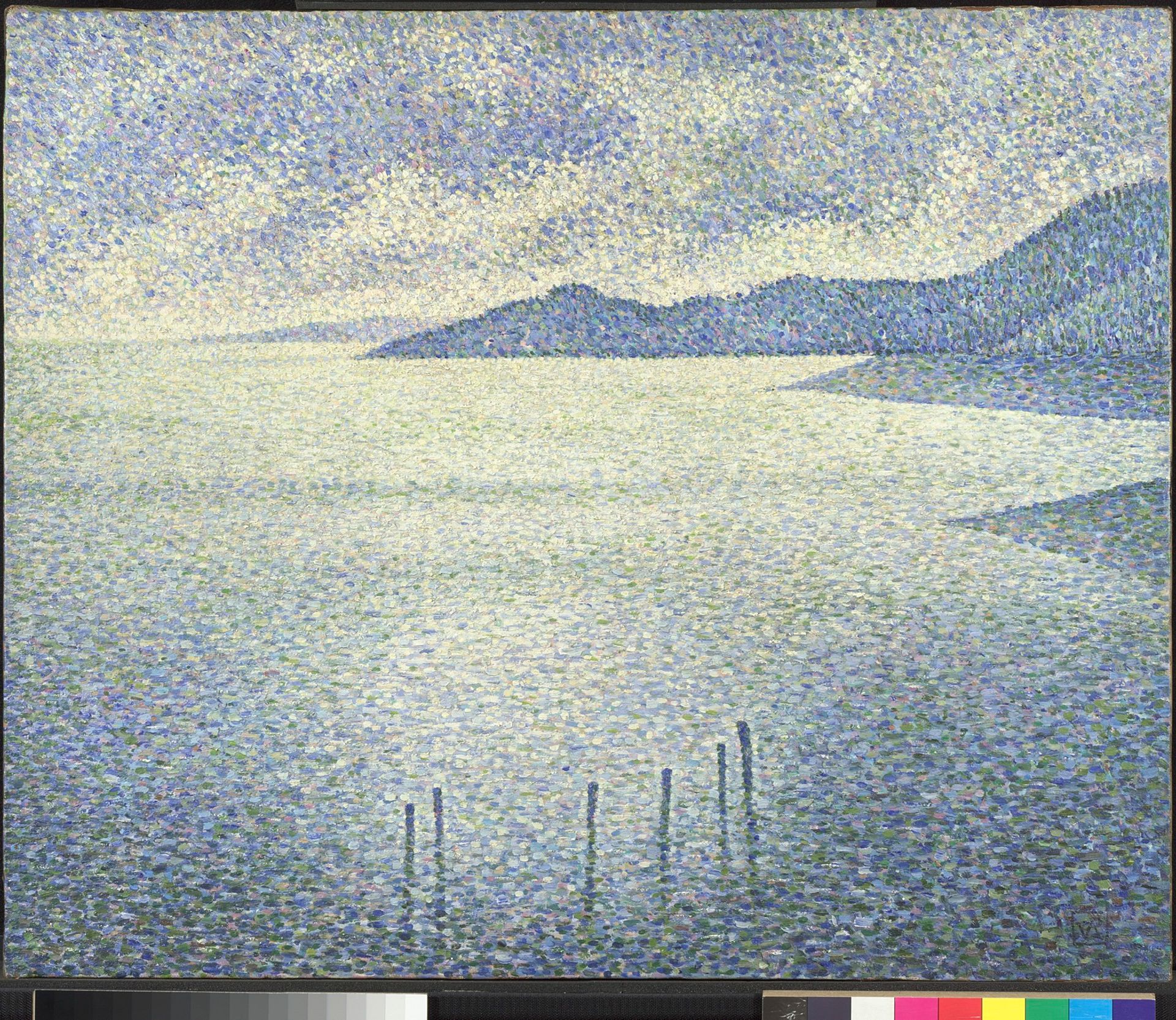

Wow, this exhibition has certainly divided responses across the arts! The music world has been generally enthusiastic, while it has generated near-universal opprobrium from art critics. As someone who often dons earplugs in art galleries I wasn't overly optimistic and there are many unfortunate, clunky literal moments that do the paintings in question no favours: most notably the wildlife sounds by Lake Keitele (1905) and the “soundtrack” accompaniment to Paul Cézanne’s Les Grandes Baigneuses (around 1894-1905). Then Cardiff and Miller’s school-project-esque model of the architectural setting of Antonello da Messina’s St. Jerome in His Study (around 1475) accompanied by clomping, whinnying and stamping, is completely at odds with the painting’s tiny scale and meditative silence. I may be alone among my art world compadres but I enjoyed the way that Jamie xx’s spots of sound divided or coalesced depending on how near you were to Théo van Rysselberghe pointillist painting, corresponding to how the paint dots work on the retina. And I thought Susan Philipsz’s austere broken-string violin tribute to Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533) was one of the best things she’s done. So, although a curator’s egg-of-a-show, there were enough good parts to keep me from reaching for my earplugs.