On the heels of the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) tarred-and-feathered Bjork exhibition, several critics, including Christian Viveros-Faune of Artnet, predicted that Klaus Biesenbach’s next venture, a Yoko Ono survey, would be another bubble-brained capitulation to upper-middlebrow celebrity culture. Ono was just collateral damage in the internet’s crusade against Biesenbach. This pre-emptive dismissal of her work was made possible by the occlusion of her artistic achievements by her ironclad identity in popular culture as John Lennon’s widow, a prejudice the MoMA show neatly corrects. Focusing on her classical period between 1960 and 1971, Yoko Ono: One Woman Show (organised by Biesenbach and Christophe Cherix, the museum’s head of drawings and prints) proves its case for Ono as a seminal avant-gardist on equal footing with the established male neo-dada canon fodder: John Cage, Nam June Paik, George Maciunas.

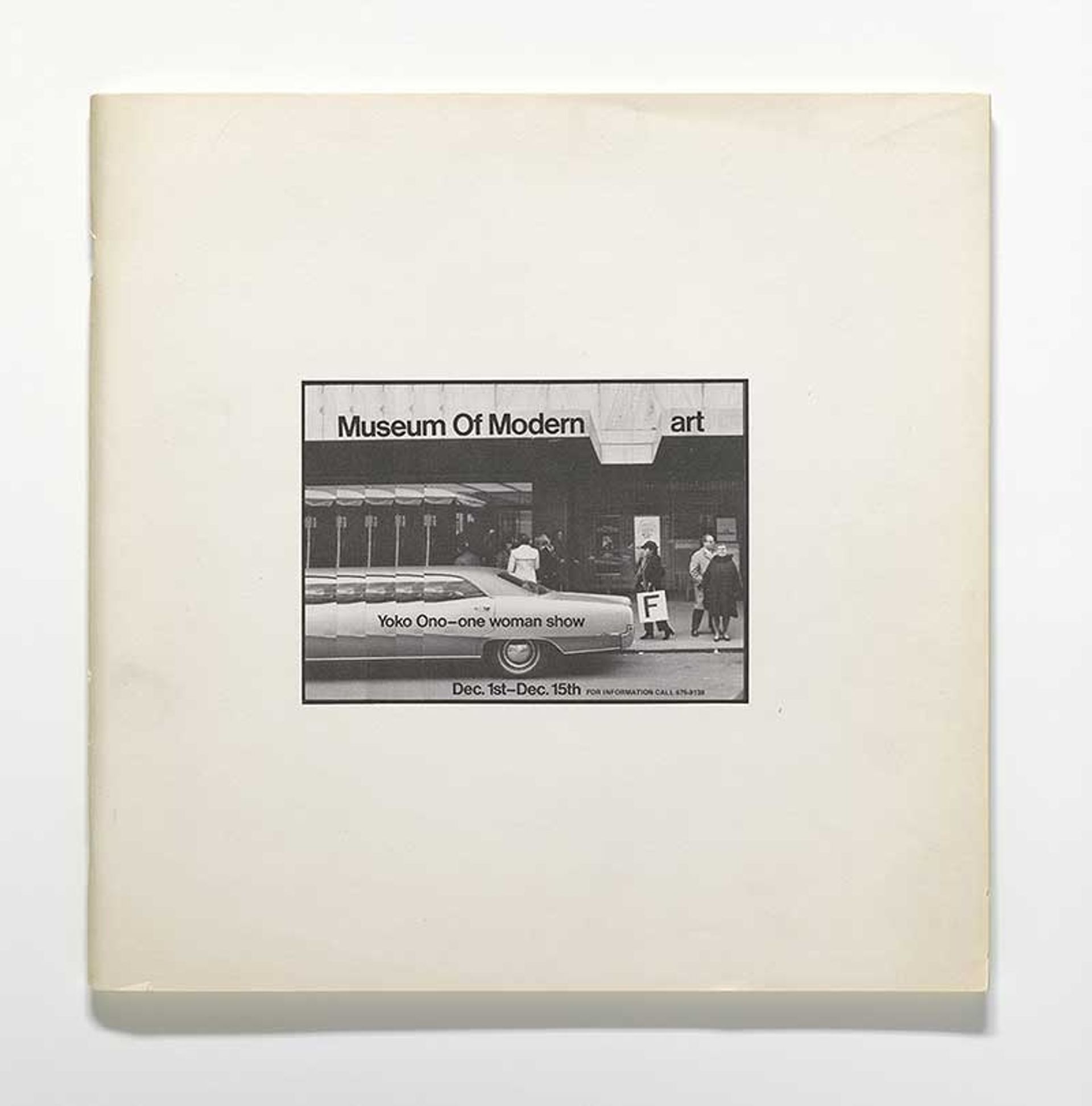

The show’s title is an institutional nod to Ono’s unsanctioned—some would say nonexistent—MoMA exhibition of 1971. In a conceptual art project-cum-publicity stunt, Ono took out a page in the Village Voice advertising her own fictitious solo show, irreverently titled Museum of Modern [F]art. In place of a conventional art exhibition, misinformed MoMA visitors were bemused to find a man wearing a sandwich board informing them that Ono had released a swarm of flies sprayed with her favorite perfume throughout the museum. “Read as a guerilla insertion by a woman of color” into the temple of modern art, Ono’s first unauthorised MoMA show was, as the art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson puts it her catalog essay, “like a fart: an unwelcome emission, a vulgar, odious eruption that violates standard practices of museum respectability.”

That may sound like a stretch, but bathroom humor is in fact a crucial part of Ono’s approachable, body-oriented brand of conceptual art and her eccentric humanist politics. “We are forever apologetic for being real,” she wrote in “The Feminization of Society,” her 1972 manifesto espousing a kind an emotive rectal feminism: “Excuse me for farting, excuse me for making love and smelling like a human being, instead of that odorless celluloid prince and princess image up there on the screen.” In Ono’s banned 1966 film No. 4 (also called Bottoms), hundreds of buttocks wag back and forth while their owners (including Ben Patterson, Carolee Schneemann and Ono herself) walk on a treadmill. The piece satirises the celebrity-driven charisma cult of the mainstream film industry, swapping actors for mooning tuchuses.

The body is also the locus of Ono’s best-known work, the widely-influential Cut Piece, documented in Albert and David Maysles’s film of the performance at Carnegie Hall in 1964. Kneeling, Ono places a pair of scissors in front of her and invites audience members to approach, cut off a scrap of her clothing and keep it as a souvenir. I is far from the poker tournament of sadistic violence that characterises Marina Ambramovic's later work Rhythm 0 (1974), her infamous six-hour endurance piece where the inert, wholly submissive artist allowed the audience to pick and prod at her body using 72 objects, including a loaded gun.

While Ambramovic's sensationalist performance degenerated into an orgy of molestation and vampirism, Ono’s more quietly unnerving Cut Piece has been interpreted, variously, as a parable of Buddhist renunciation, a literalisation of the male gaze, a traumatic working-through of the US bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—though none of these interpretations feel entirely satisfactory. Considered alongside Ono’s feminist writings, it reads as an allegory of stereotypically “feminine” qualities: submission and generosity. In essentialist rhetoric typical of the moment, she argued that passivity could be revalued and deployed to build an “organic, noncompetitive society that is based on love, rather than reasoning.” The trope of female nakedness and vulnerability reappears in Ono’s 1970 film of a housefly exploring the body of a recumbent naked woman, resting momentarily on the tip of her nipple (Fly, 1970).

The “job of an artist,” Ono maintained, was not to make things, but to communicate. “Artists must not create more objects,” she wrote in 1971, “the world is full of everything it needs. I’m bored with artists who make big lumps of sculpture and occupy a big space with them and think they have done something creative.” For an artist who maligned object-making and excelled in language and film-ready performance, it comes as no surprise that her sculptures are the weakest works in the MoMA exhibition. The show opens on the lame one-liner of Apple (1966), a readymade assemblage consisting of a granny smith resting on a Plexiglas pedestal. The exhibition’s self-styled piece de resistance is the crowd-baiting interactive installation To See the Sky (2015), a spiral staircase leading to a skylight in the gallery’s ceiling. The only new work commissioned for the show, it lacks the experiential payoff to justify the long lines. The relative poverty of Ono’s sculpture is exacerbated by conservative curating. Several of the participatory works from Ono’s 1966 London show at Indica gallery are regrettably roped off, inviting familiar complaints about the “museum-as-mausoleum” and the “institutionalisation of the avant-garde.” A notable exception is the lapidary, conceptually elegant White Chess Set (1966), which museumgoers are allowed use during prescribed hours. A beautiful object in its own right, it invites the participants to play until they can no longer distinguish their pieces from their opponent’s (all the pieces are white), dissolving a Manichean contest into a ludic exercise of non-dualism and benign chaos.

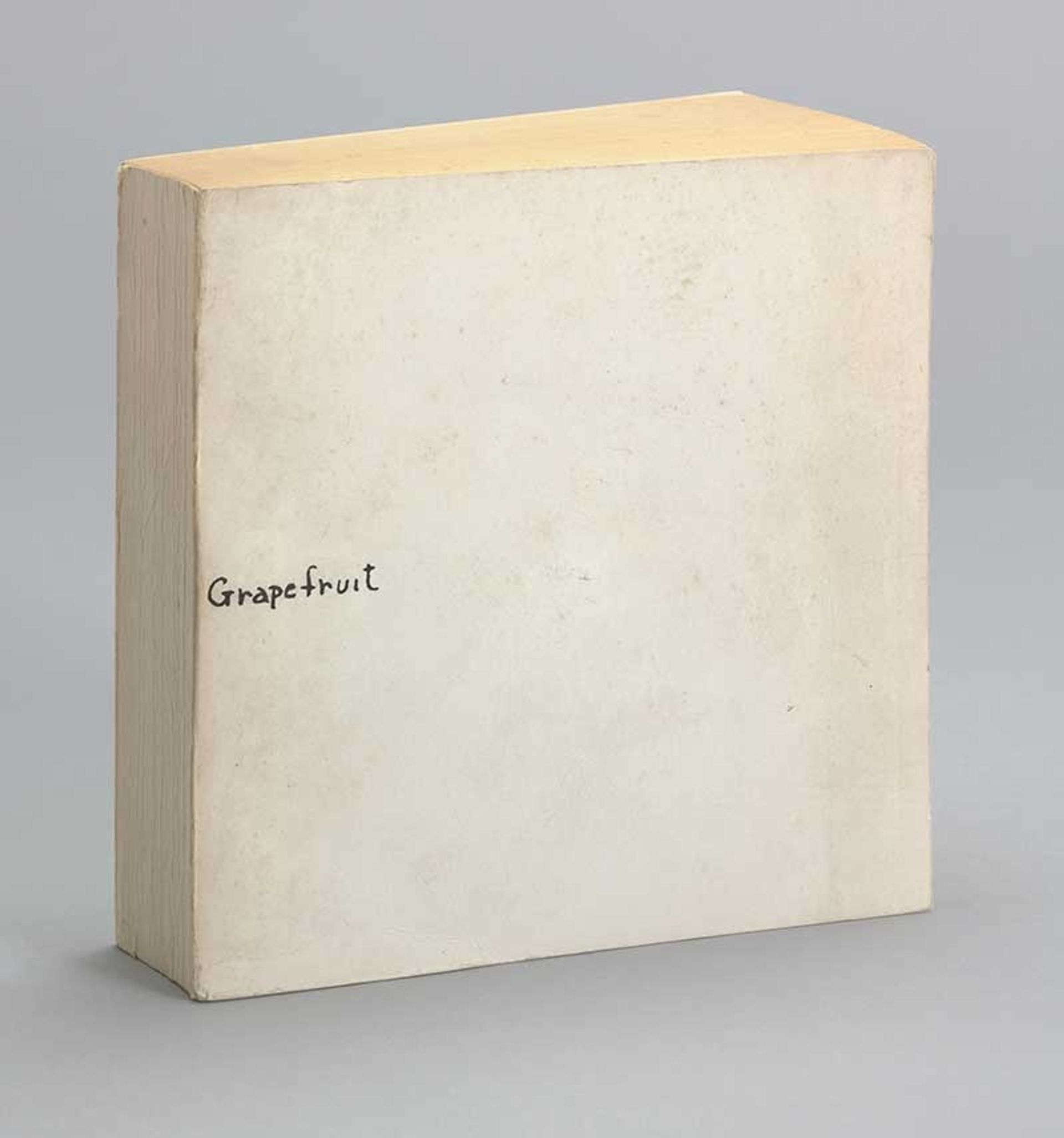

The true climax of the exhibition is the deservedly admired artist book Grapefruit (1963-1964), consisting of 151 typewritten instructions framed and mounted as a series. Light-years away from of the bone-dry tautologies of Joseph Kosuth or the technocratic directives of Sol Lewitt, Grapefruit collates crisp tweet-sized prompts, ranging in tone from eccentric yet attainable (“polish an orange”; “draw line, erase line”) to purely Platonic (“make all the clocks in the world be fast by two seconds without letting anyone know about it”; “send the smell of the moon”) to just plain weird (“smoke everything you can, including your pubic hair”).

Grapefruit’s appeal to the imagination as the endpoint of fully dematerialised art would become the source material for Lennon’s inescapable hippie-humanist ballad, “Imagine,” the best selling single of his solo career. “It should be credited as a Lennon/Ono song,” Lennon said in a BBC radio interview two days before he was killed, “A lot of it—the lyric and the concept—came from Yoko, but in those days I was a bit more selfish, a bit more macho, and I sort of omitted her contribution, but it was right out of Grapefruit” By way of Ono, the gambit of “advanced” postwar art became a protest culture meme.

While the significance of Ono’s word scores and performances is taken for granted by historians of postwar avant-garde art, in mainstream culture, she has been an object of racist caricature, misogynist paranoia, and cultural conservative obloquy. She has been smeared as a carbuncle on the face of rock-and-roll, the “dragon lady” who destroyed the Beatles. With its unapologetic uplift, Ono’s art raises a gleeful middle finger at her haters. This dreamy optimism is, of course, a relic from another time. “Artists can change the world into a Utopia where there is total freedom for everybody,” she wrote in 1971. While the half-baked messianism and willful naiveté of this statement sounds embarrassingly historical, Ono’s challenging and generous early work—as a third term beyond the stalemate between pompier hermeticism and pseudo-populist commerce —feels more relevant then ever.

Chloe Wyma is a freelance critic and PhD student in art history at the City University of New York Graduate Center.

Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 7 September