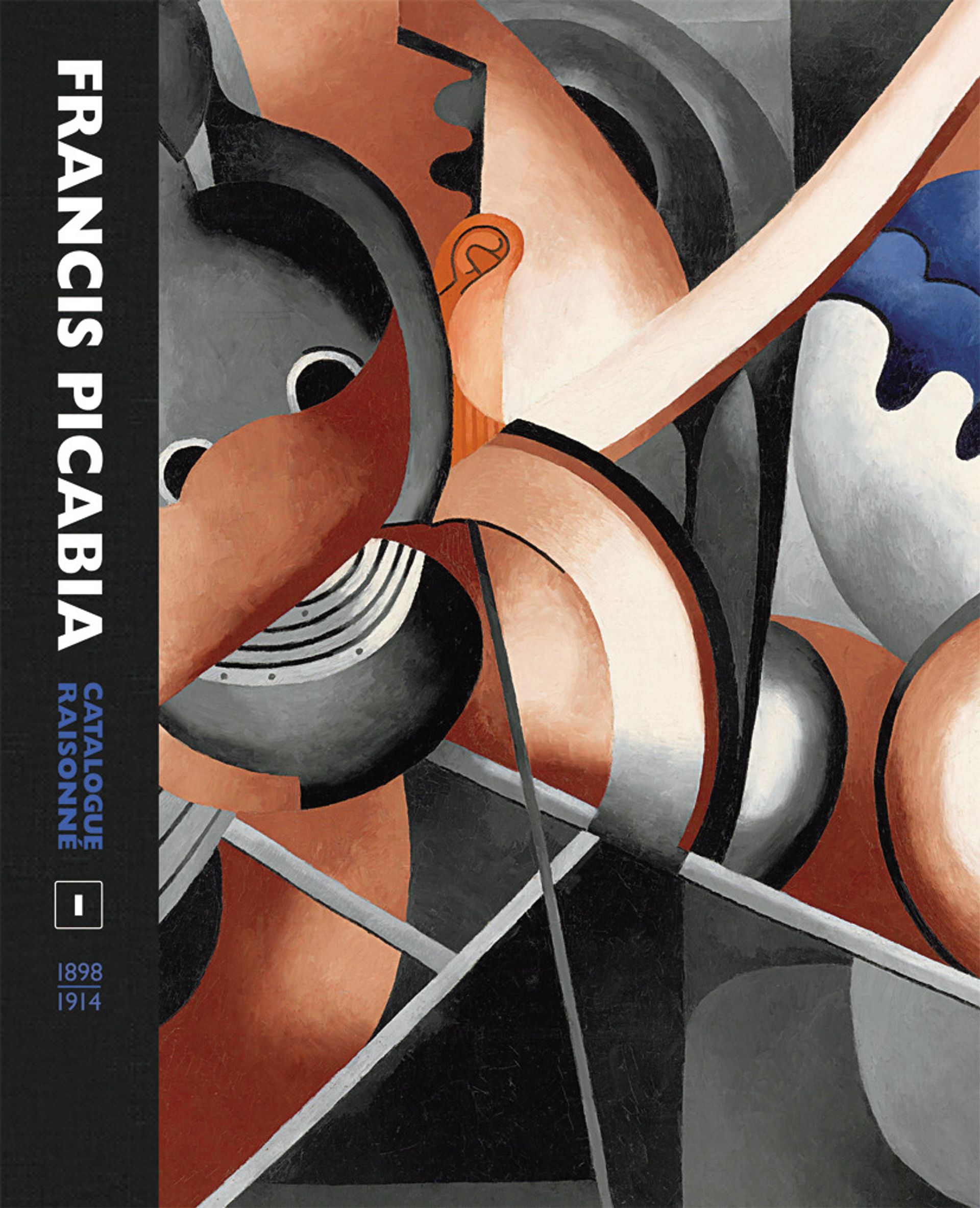

It is a truism that Western culture has a tendency to absorb dissenters and co-opt rebels by transforming their opposition into a marketable commodity. This truism is never more evident than in the exhaustive and expensive cataloguing process for art that was considered to be marginal, worthless provocation when it was made. Few artists were as disruptive and irreverent as Francis Picabia (1879-1953). As an original member of the Dada movement and then a Surrealist, he mocked social mores. Later, in straitened circumstances, he produced a series of kitsch pin-up paintings that seemed to blot his copybook as an avant-gardist, but which have in recent years been taken up by proponents of Post-Modernism and Bad Art.

Conventional start

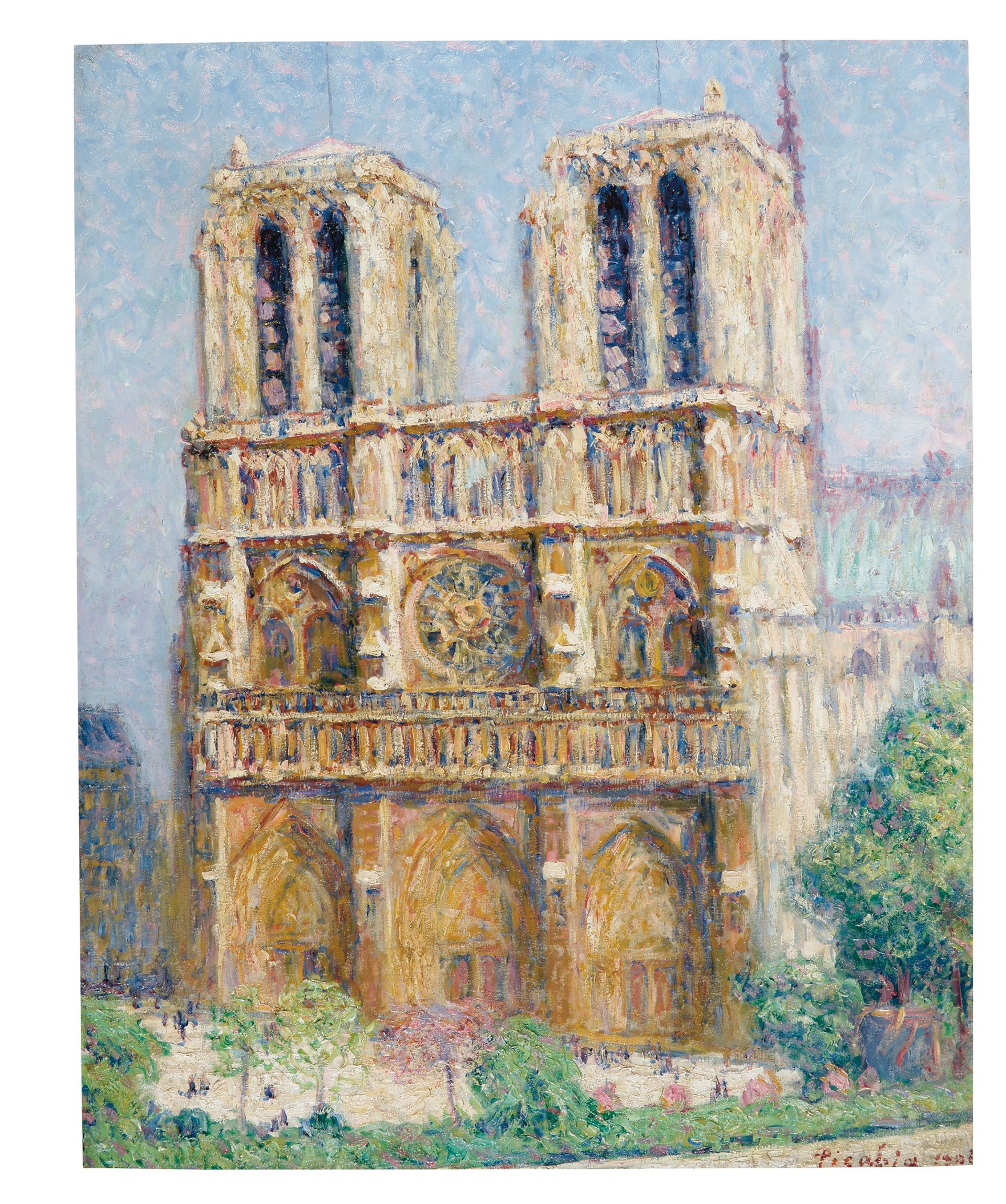

Produced under the guidance of the Comité Picabia, this first volume of the catalogue raisonné, Francis Picabia Catalogue Raisonné: 1898-1914, establishes that Picabia’s origins could not have been more comfortable and conventional. Born in Paris into a Franco-Spanish haut bourgeois family, Picabia began as an Impressionist painter in the early 1900s. His proficient and attractive landscapes and seascapes in the style of Sisley met with commercial and critical success, though the haystacks and cathedral façades were criticised as being derivative of Monet. More than half of the 491 works in this volume are the work of Picabia as a late follower of Impressionism rather than a pioneer of revolutionary art.

Picabia decided to leave behind the security of Impressionism in 1909, which led to a break with his dealer. The painter quickly proceeded through more advanced art styles: a dalliance with the Divisionism of Signac was succeeded by Fauvism. A painting of cows (around 1911) foreshadows the direct, simplified style and guileless child’s-primer character of some later paintings, but there is little indication of his mature output. By 1912, Cubism, Futurism and Orphism blended in Picabia’s compositions. At times his work was nearly or actually abstract and genuinely adventurous, fluctuating between serious and flippant modes. Apollinaire (who identified a noticeable trend towards abstraction in painting) became a friend of Picabia and wrote laudatory reviews.

As an exhibitor in annual salons and the La Section d’Or exhibition (which introduced the Orphist movement to Paris), Picabia was a leading figure in the avant-garde by late 1912, hence his inclusion in the Armory Show in New York the following year.

In anticipation, Picabia and wife Gabrielle crossed the Atlantic. Being on hand in New York during the exhibition meant that Picabia was interviewed by the press and – consequently or not – his Orphist art became one of the most prominent lightning rods of the display, attracting considerable praise and derision. During the couple’s stay of three months, Alfred Stieglitz staged a solo exhibition of Picabia’s art at the 291 gallery, attendance at which was boosted by the Armory controversy.

By late 1913, Picabia’s forms had taken on a mechanical appearance, influenced by illustrations of new technology. It only required the artist’s proclivity for mockery – combined with the nihilism of wartime – for the artist to take one step further to reproduce and parody these technical illustrations outright. The stage was set for Dadaist subversion of fine art, utility and science – and the society they served.

The sum of its parts

The cataloguers have decided to end the volume with Picabia in wartime military service (which caused a creative hiatus) and on the brink of his Dadaist period. This is the first of four volumes; others will cover 1915-27, 1927-39 and 1940-53. William A. Camfield provides a narrative of the artist’s development up to 1914, and Arnauld Pierre’s essay explains the links between dance, the physical exercise craze and Picabia’s painting. Candace Clements discusses four colour intaglio prints that Picabia produced during his Impressionist period. The prints are closely related to his landscape oils and exhibit a high degree of technical sophistication. These prints, editioned by the master printer Eugène Delâtre, have been neglected by historians, perhaps because they lie outside the heyday of Impressionism and are atypical of Picabia’s mature styles.

This series promises to be a fascinating investigation of an unpredictable, innovative artist, whose work frustrated and perplexed supporters and opponents over the course of a productive life.

Alexander Adams is a British writer and art critic. His most recent book of poems and drawings, The Crows of Berlin, was published this year by Pig Ear Press

Francis Picabia Catalogue Raisonné, Volume I: 1898-1914

William A. Camfield, Beverley Calté, Candace Clements and Arnauld Pierre

Mercatorfonds, in collaboration with Yale University Press, 424pp, £150, $250 (hb); in English and French