Scholarly and artistic interest in 3-D effigies that seem eerily alive tend to run in parallel. The pioneering essays on Medieval and Renaissance waxwork portraits by Aby Warburg (1902) and Julius von Schlosser (1911) coincided with “statuemania” and herald the fascination with statues, statuesque figures, masks and mannequins of de Chirico, Dada and Surrealism. A hiatus occurred with the post-war triumph of Modernist abstraction, but William Rubin’s 1968 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage, coincided with an upsurge of performance-based art that blurred the boundaries between artifice and life. Ever since, there has been a deluge of publications and exhibitions about waxworks, automata, anatomical models, dummies, masks, life-casts and, or course, the Pygmalion myth. Three new books make a distinctive contribution, trying to put three different types of effigy into their cultural context.

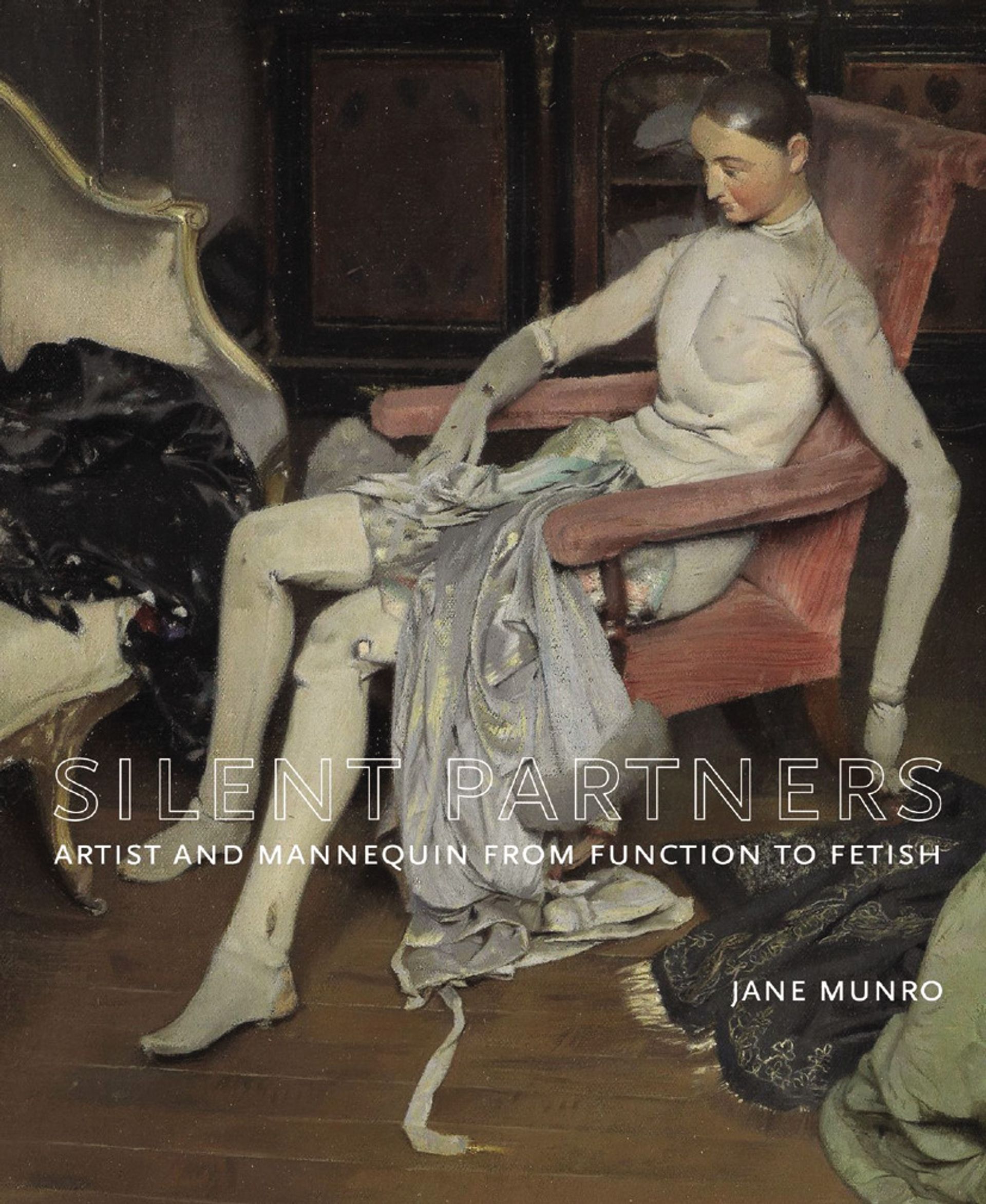

Jane Munro’s Silent Partners: Artist and Mannequin from Function to Fetish is the book-style catalogue for an intriguing exhibition that was first shown at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, where she is a curator, and is now at the Musée Bourdelle, Paris (Mannequin d’Artiste, Mannequin Fétiche, until 12 July). She traces the workshop use of mannequins or “lay figures” from the Renaissance until the 19th century. From being functional studio props, they would move into the expressive foreground once depictions of artists’ studios proliferated, and also with the rise of mechanistic/materialist theories of man and the “uncanny”. She ends with shop dummies, Surrealism and the Chapman Brothers.

Never “flesh and blood”

Munro identifies two basic sizes of workshop mannequin. Small figurines, similar to sculptors’ modelli, helped artists plan a pose or an entire composition; Poussin is the most famous exponent of the latter, and the exhibition featured a remarkable mock-up of a stage set with dressed clay figurines placed in front of the Fitzwilliam’s stunning new acquisition, Extreme Unction (around 1638-40). Life-size models with some degree of articulation were generally used for drapery studies by artists as eminent as Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Subsequently, we find mannequin owners such as Gainsborough and Courbet accused of painting doll-like figures that could never be mistaken for “flesh and blood”. One of the big revelations is a series of paintings from the late 1920s by the little-known British painter Alan Beeton in which his androgenous but feminine mannequin is put through its paces in a bleakly chaotic room; in one picture, the disembodied head lies on the floor.

My main criticism of this fascinating project is the lack of historical perspective in relation to a major section entitled “Woman Mannequinised”, which begins in the late 19th century and culminates with Surrealism and its unruly offspring. Munro’s “seminal” work is Degas’s portrait, around 1878, of the painter Henri Michel-Lévy in his studio, sullenly leaning up against one of his Déjeuner-sur-l’herbe-style pictures. A dressed, life-size female mannequin lies slumped with knees apart on the floor beside him, her head thrown back. Munro aptly suggests Degas anticipates the work of Hans Bellmer “in making us aware of intimations of a latent sexual violence between male artist and female mannequin”. She further claims Degas would have been familiar with photographic records of patients at psychiatric hospitals. As an assiduous student of antique sculpture, Degas is more likely referring to the Niobid group, where Niobe’s daughters and sons were shot with arrows as punishment for their mother’s pride (the weeping Niobe was turned to stone). The mannequin’s pose closely resembles that of one of the dying sons; paintbrushes project from the painter’s palette like a sheaf of arrows. A woman slumped against the base of a tree in one of Michel-Lévy’s pictures is modelled on one of Niobe’s daughters. The anguished heads of the Niobids were available as plaster casts and were included in images of artists throughout the Baroque; the artists’ manhandling of them proved they possessed the power of life and death. The history of the mannequin in Modern art cannot be disentangled from the history of the antique plaster cast.

Extraordinary period

Assaf Pinkus’s Sculpting Simulacra in Medieval Germany, 1250-1380 is the first English-language study of an extraordinary period in German sculpture, extending from the celebrated founders’ statues in Naumberg Cathedral and the Bamberg Rider, to the balcony figures on the Church of St Mary in Mülhausen and Peter Parler’s bust portraits in St Vitus Cathedral in Prague. Pinkus usefully summarises the countless competing interpretations to explain these largely unprecedented figures, and has a good bibliography. But she believes iconographic and stylistic comparisons only get us so far. The often perplexing individuality and lifelikeness is due to the sculptors’ desire to create “real presences”, and the Pygmalion-like sensuous immediacy of the figures temporarily defers a religious or social response. There are echoes of Gombrich’s “making and matching” theory—each great artist adds a new bit of “reality” to existing artistic models—and so we are left little the wiser as to why “reality” should look so different to each artist, and in what way their “sensuousness” is more “immediate” than their predecessors’. But Assaf’s provocative book should encourage more anglophone scholars to study these marvellous works.

Shivers down the spine

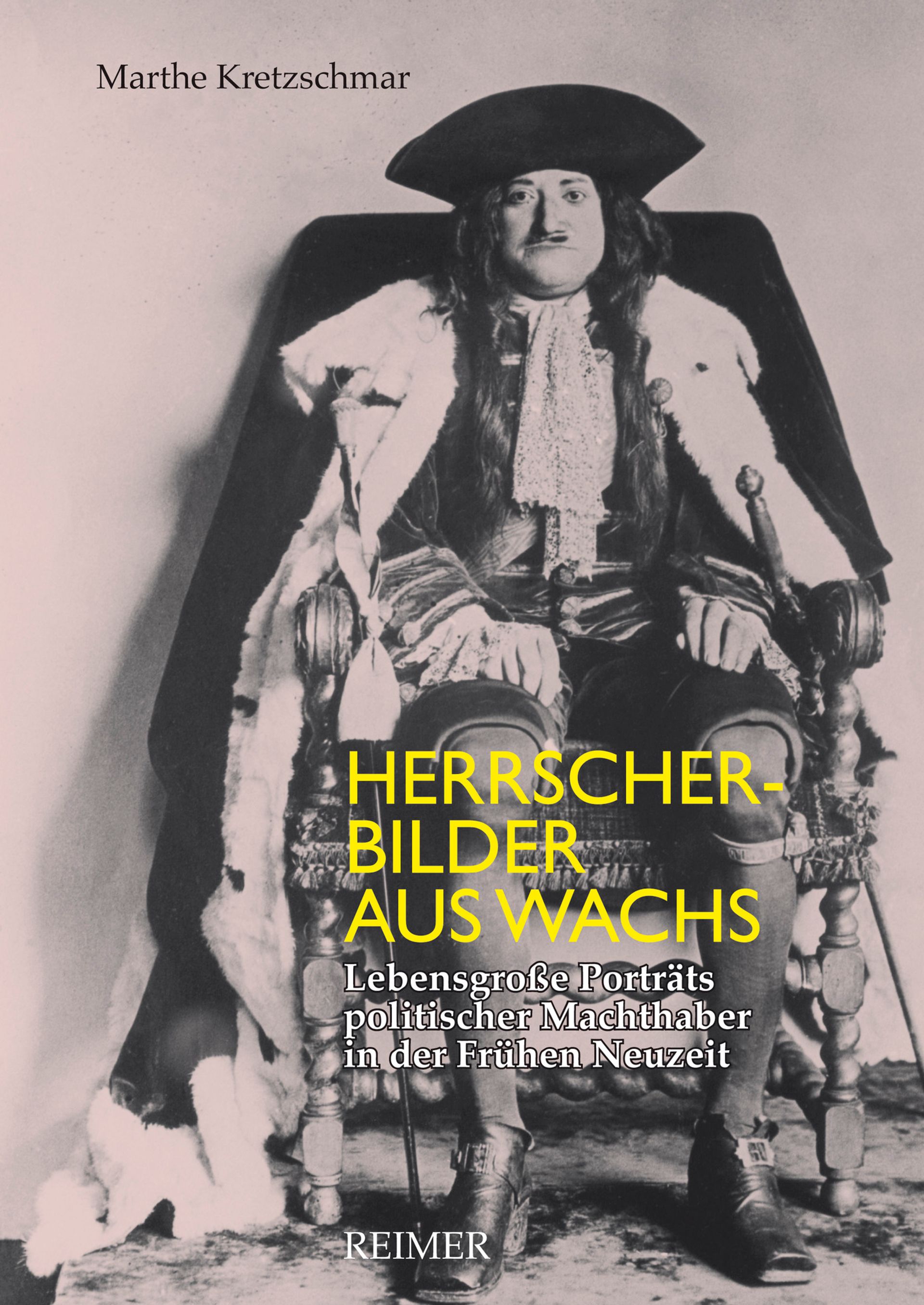

Marthe Kretzschmar’s Herrscherbilder aus Wachs is an invaluable survey-cum-inventory of the different types of life-size wax ruler portraits—clothed, with glass eyes and real hair—produced in the German-speaking world from 1600 to 1800. She divides them into eight major categories and many more sub-categories, and these will be helpful for anyone studying a genre that never fails to send shivers down the spine. They represented the rulers at their funeral services and subsequently could be found in churches, Wunderkammern or palaces, such as Rastrelli’s enthroned waxwork of Peter the Great in the Winter Palace.

These “ancestor portraits” suggested the continuing presence and cultic power of the deceased, giving these mostly minor potentates the same treatment that had once been given to European kings (examples survive in Westminster Abbey). They went out of fashion in Germany after the Napoleonic Wars, when Enlightenment values swept away many old belief systems. Perhaps, too, they lost their cachet with the rise of the waxwork museum and then of photography. But the practice has never entirely died out. The “auto-icon” of philosopher Jeremy Bentham, on view at University College, London, since 1850—and even the waxwork of the Anglo-American collector Alfred Gilbert (last seen with his collection in Somerset House and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s store)—show how the practice spread to non-rulers. Last but not least, a German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann invented formaldehyde in 1867, which meant that the embalmed bodies of Lenin and Stalin could easily outclass the enthroned waxwork of Peter the Great.

Although publishers will never really warm to books about sculpture (too drab, difficult and costly to reproduce), we have been living through what will perhaps come to be regarded as the golden age of writing about three-dimensional work of both the past and present; the last half-century is rivalled only by the era of Winckelmann, Herder and Falconet. These three interesting books suggest that there is still much more to be said.

James Hall is the author of The World as Sculpture and, most recently, The Self-Portrait: a Cultural History

Silent Partners: Artist and Mannequin from Function to Fetish

Jane Munro

Yale University Press, 275pp, £40 (hb)

Sculpting Simulacra in Medieval Germany, 1250-1380

Assaf Pinkus

Ashgate, 264pp, £65 (hb)

Herrscherbilder aus Wachs: lebensgroße Porträts politischer Machthaber in der Frühen Neuzeit

Marthe Kretzschmar

Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 299pp, €40 (hb); in German only