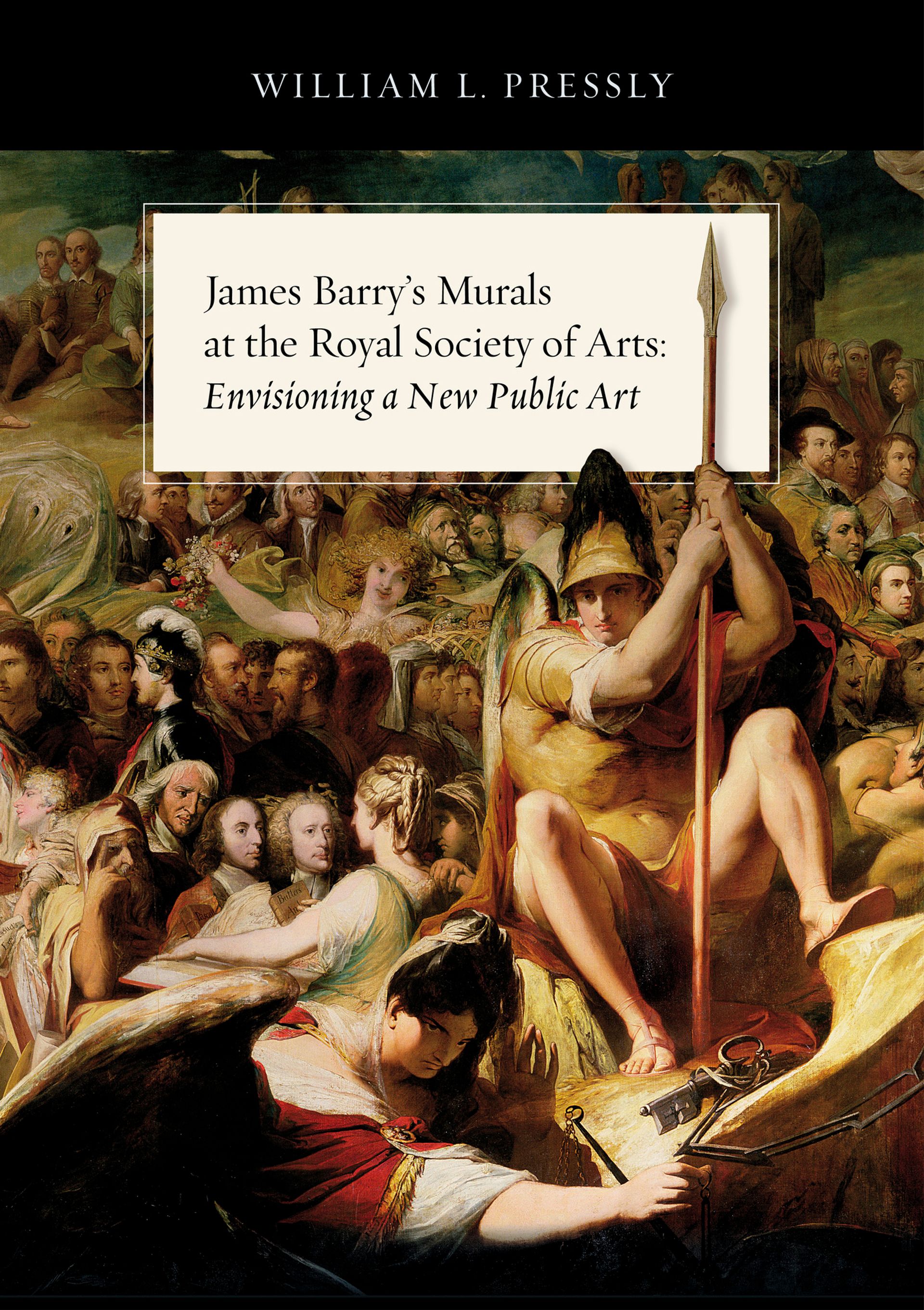

Cork-born James Barry (1741-1806) is probably best known these days as, until recently, the only artist ever to be expelled from the Royal Academy. Idealistic, combative and fiercely intelligent, Barry at the height of his career engineered for himself by far the most important public commission for painted decorations given in Britain between Thornhill’s Painted Hall at Greenwich in the 1720s and the redecoration of the Houses of Parliament over a century later. His six huge paintings, Pictures on Human Culture, were completed for the (now Royal) Society of Arts’ Great Room in 1784, and they are still in situ—a classic, little-known Great Sight of London. That the cycle has remained so unfamiliar is not a comment on its artistic quality; standing beneath the paintings induces goose bumps and reveals at once why, after his death, Barry was honoured with a public funeral in St Paul’s. More problematic is their uncompromisingly lofty intellectual underpinning, arguably already old-fashioned in its time, not to mention the impenetrability of their iconography, which the artist’s own written guides do not entirely clarify.

Bill Pressly has devoted much of his career to championing Barry, and James Barry’s Murals at the Royal Society of Arts: Envisioning a New Public Art is its triumphant culmination. Its chief purpose is to provide a comprehensive exegesis of the iconography of the cycle on two levels: the first (itself dense enough) the superficial one of what Barry optimistically expected the learned spectators of his pictures to understand at once; but, second, a deeper level only at which would the true meaning of the cycle stand revealed, and which Barry chose largely to conceal, offering visual hints which gave no more than discreet pointers to his true intentions. Although there are signs that certain of Barry’s contemporaries (such as William Blake) did grasp the real meaning of the cycle, its lack of purchase on posterity was undoubtedly a result of the elusiveness of the central theme. Part of the explanation for Barry’s reticence is that he believed all great works of art required to be contemplated and their meanings teased out at length; but part was that the central message closely identified the progress of human culture with the achievements of the Roman Catholic church, a position far too controversial in the London of the Gordon Riots to adopt in a public work.

Pressly’s elucidation of Barry’s intentions is absolutely convincing and magisterial. Although he is not exhaustive on every aspect of the paintings’ production, he takes the trouble to follow through Barry’s myriad changes of mind and abortive ideas, as well as the variations introduced in the print versions of the cycle. Pressly’s erudition in locating Barry’s literary and artistic sources is unfailing, and he has a profound understanding of the artist’s creative processes. Perhaps it is this unswerving but, in these times, unfashionable commitment to “artistic intention” that explains the book’s initial, scarcely credible vicissitudes at the hands of publishers; fortunately, on sight of the text the university press in Barry’s home town had no qualms, and they are to be warmly congratulated on having lavished on the volume the production values that it fully deserves. Amid so much merely fashionable writing, this is proper art history, living in and recovering the past, enriching our understanding of the way artists thought in a way that very few recent books on 18th-century British art can claim to have done.

Alex Kidson was the curator of British art at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, for more than 25 years until 2008. Since then he has been a special projects Fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, working on a complete catalogue of paintings by George Romney, which is due to be published by Yale University Press this summer

James Barry’s Murals at the Royal Society of Arts: Envisioning a New Public Art

William L. Pressly

University of Cork Press, 396pp, €49 (hb)