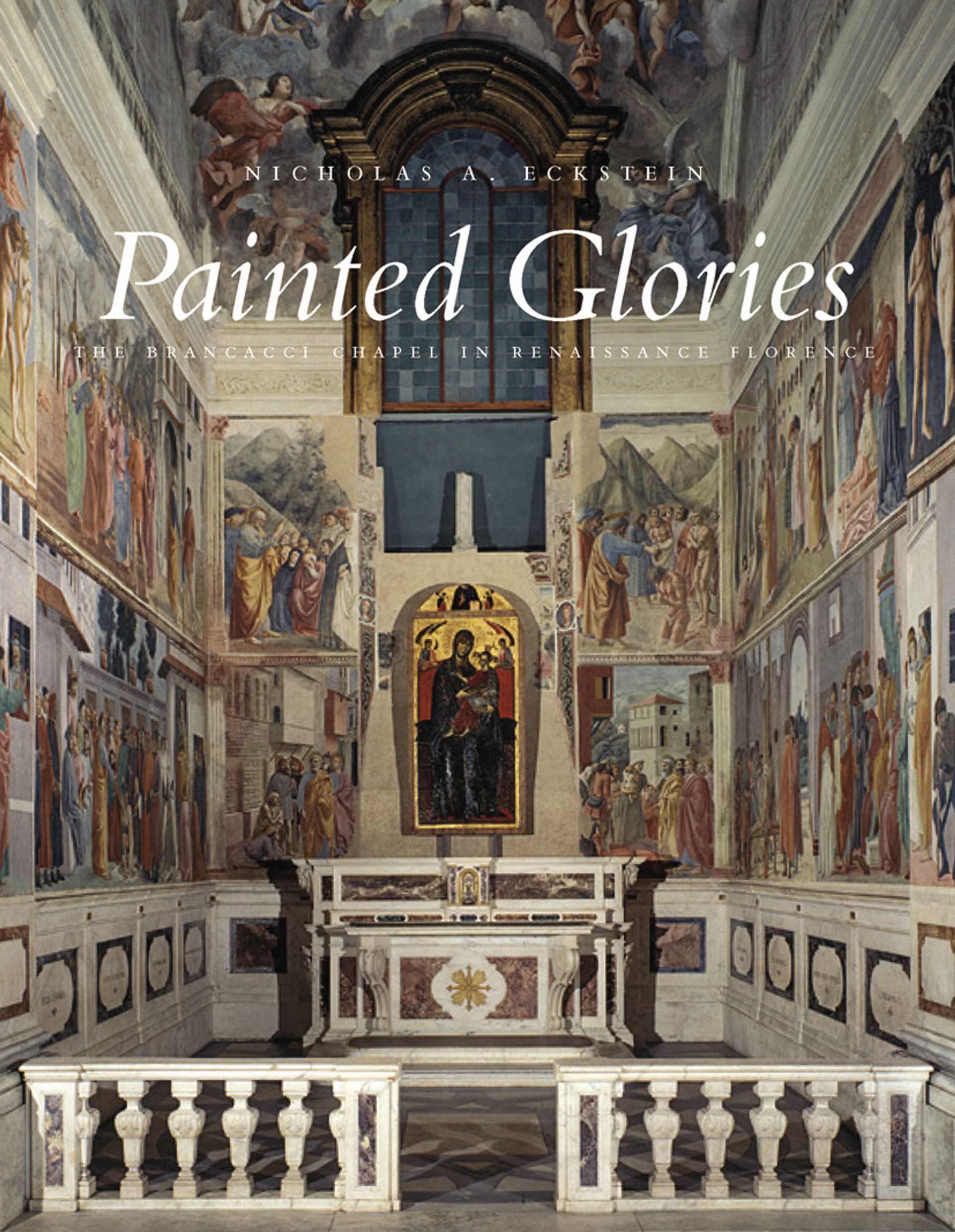

As is well known, the Brancacci Chapel frescoes in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence—begun by Masolino, who was then joined by Masaccio, and, years later, completed by Filippino Lippi—played an outsized role in formulating the revolutionary painting style of the early Italian Renaissance. Still, no documents regarding their commission and production have ever come to light. But it seems safe to say that, ever since a revelatory conservation project was completed in 1990, what we know of the cycle’s subject matter, its message and the individual roles played by Masolino and Masaccio in its execution has doubled.

This is the background to the publication of Painted Glories: the Brancacci Chapel in Renaissance Florence. In 2003, its author, Nicholas Eckstein, organised a symposium on the subject and then edited the component talks, with an introductory essay, in an important, wide-ranging publication (The Brancacci Chapel: Form, Function and Setting, 2007). In his latest tome, Eckstein sets out to apply “previously unused circumstantial evidence to infer how contemporary Florentine women and men would have perceived, understood and used the Chapel”. To be sure, documenting such responses is no easy task, given their subjective, not to mention transitory, nature. Yet Eckstein, a seasoned historian who has specialised in the socio-economic and devotional networks of 15th-century Florence, has mined the city’s archives in great depth, as an examination of this book’s footnotes attests.

The parish of Santa Maria del Carmine was the setting for a lively nexus of lay confraternities, some of which administered to the poorer denizens of this decidedly two-class Oltrarno district. (Such activity is mirrored in the scene of Saint Peter distributing the Church’s goods that Masaccio depicted on the Brancacci Chapel’s altar wall.) Another aspect of the Carmelite church’s “sacred space” was the cluster of private chapels, of which the author provides a welcome analysis.

At the time when it was decorated by Masaccio and Masolino, the Brancacci Chapel belonged to Felice di Michele Brancacci (1382-1447), a well-connected silk merchant and sometime member of the Florentine state. Masaccio’s death in around June 1428 and Brancacci’s exile from Florence around ten years later meant that work on the fresco cycle came to a halt. Funds for its completion may have already been depleted, or had perhaps reverted to the coffers of the Carmelite authorities. As Eckstein stresses, the chapel, its decoration and programme amounted to “a cultural product in active dialogue with its immediate environment, constantly refashioned by evolving patterns of use”.

As its historical context changed, a growing urgency developed to complete what was, in any case, a major city landmark. Such an occasion, conjectures the author, was the Florentine victory at the Battle of Anghiari on 29 June 1440. This was attributed to the miraculous intervention of Saint Peter, whose feast day (along with that of Saint Paul) it was. As a result, the prestige of the Brancacci Chapel murals—the most important Petrine representation extant in Florence—grew accordingly. Added lustre also devolved upon the Carmelite Order.

Medici gets involved

New funding for the project materialised in subsequent years. One source was the bequest of one Antonia Velluti de Mezzola in 1479. Another, according to Eckstein’s hypothesis, was that of Fra Giovanni di Giovanni in 1469, who became the prior of the convent one year later. In the final chapter, the author notes Lorenzo de’ Medici’s increasing support for Santa Maria del Carmine; he may well have had a deciding role in the selection of a favoured painter, Filippino Lippi, to finish the frescoes. Another patron of Lippi, Piero del Pugliese, whose Oltrarno family had recently risen to prominence, might also have been solicited for support by the Carmelite friars, Eckstein suggests.

Eliot W. Rowlands is the senior researcher at Wildenstein & Co, New York. A specialist in early Italian painting, he is the author of Masaccio: Saint Andrew and the Pisa Altarpiece (2003)

Painted Glories: the Brancacci Chapel in Renaissance Florence

Nicholas Eckstein

Yale University Press, 288pp, £40 (hb)