Gothic Wonder: Art, Artifice and the Decorated Style, 1290-1350 is the third major study of medieval architecture by Paul Binski, and the biggest; it is, indeed, almost impossible to read the book unsupported. It takes up the story from his previous work, Becket’s Crown: Art and Imagination in Gothic England, 1170-1300 (2004), to explore the rise of the English Decorated style and its influence on Europe, regarded by the author as hitherto seriously underestimated.

But, as the subtitles of both books signal, the author’s careful tracing of architectural developments provides the context for a very much more wide-ranging discussion, which here reaches not only into other artistic genres, manuscript illumination and embroidery, but also into the question of Medieval aesthetics. The last is something that Binski feels has been edged out of discussion by an insistence on ideology: the political and moralising “objectives” of art. In their place he proposes a view of Medieval aesthetics that sees them as “pluralistic and profoundly sensory”.

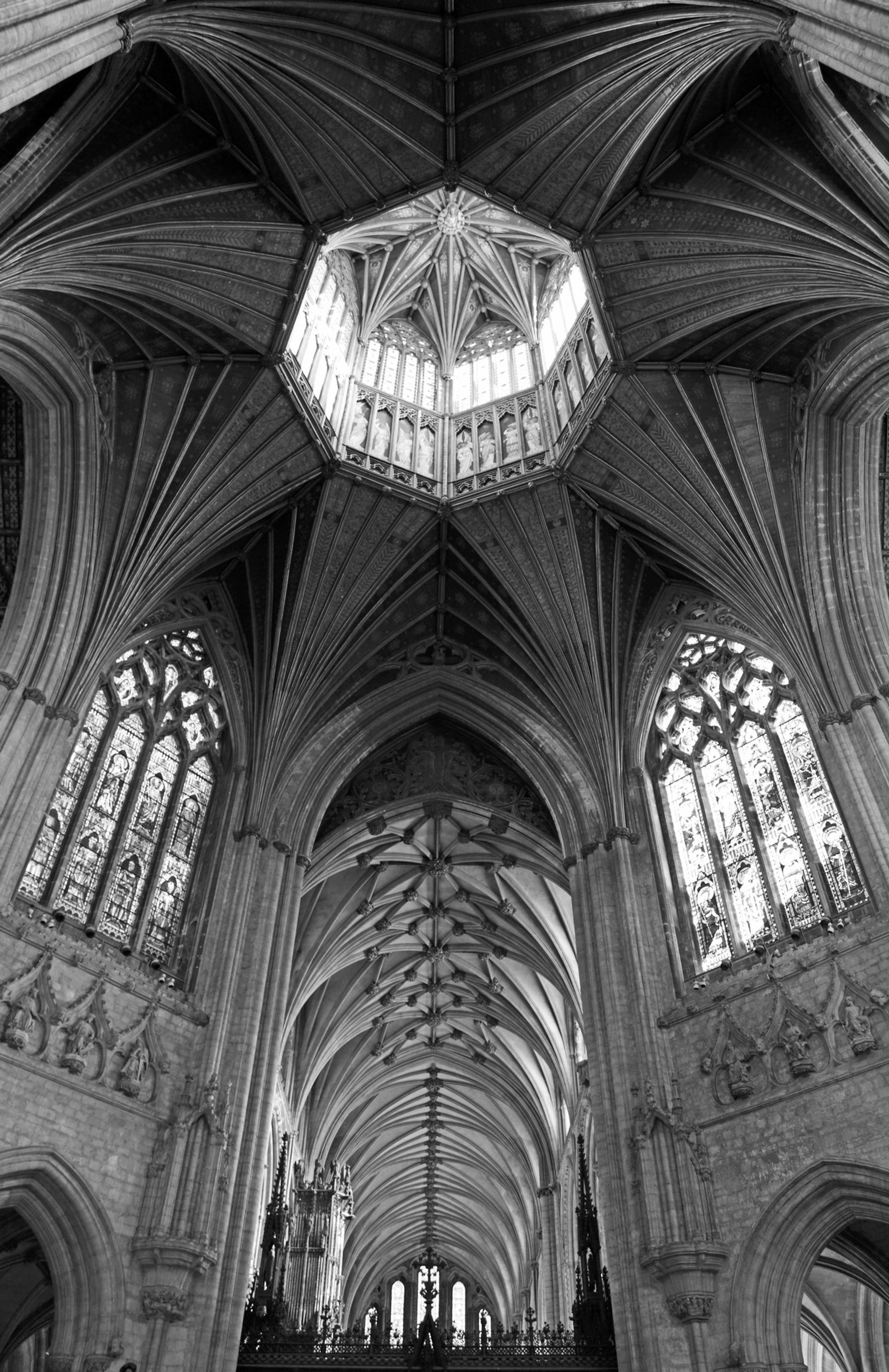

In the context of the Decorated style, this embraced varietas, defined here as artful complexity and intensity. The anticipated response was wonder—a concept that has been receiving considerable attention from historians in other fields lately, as the amazing works of nature were sorted out from the truly miraculous (the mirabilia from the miracula) across the late 12th and 13th centuries. The fact that the wonderful was both real and natural gives some support to the author’s insistence that the Continental characterisation of the English style as irrational and fantastic misses the point. Alongside wonder went enjoyment—fun, in fact. Binski sees the English style as both courtly and satisfyingly ludic, and, for him, the element of playfulness is central, something that constitutes an explicit attack on the current tendency to see the margins as more fecund than the centre: the one subversive, the other numbed by its own authority.

Quite who was actually enjoying all this is, predictably, not really clear and the author concedes as much. Most of the material illustrated here would simply not have been accessible to what might anachronistically be called the general public. But even among the elite, the oligopoly (his word) behind the tremendous eruption of patronage that underwrote the Decorated style was predominantly clerical rather than lay. But the competitiveness of secular rulers in the architectural sphere is apparent and suggests that if they knew nothing about art they at least knew what they wanted, and much of what they wanted was the production of lay craftsmen. One of the book’s themes is that this is not a period that saw building or rebuilding on a grand scale, but an interest in the construction of smaller features—tombs, Easter sepulchres, misericords—where (although this is not suggested) the individual craftsman might have a freer hand.

A contributory factor to this might be the worsening economic position. The Black Death of 1348-49 casts a shadow from the book’s earliest pages, which glance ahead as far as John Leland’s 16th-century travels with their ambivalent evocation of sore decay and fair dwellings. Less is said about the so-called agrarian crisis of the first part of the century, most recently ascribed to global climatic change, which contributed “famine” to the identification of the four signs of the Apocalypse by mid-century writers. Historians are, understandably, wary of too glib an association between the economic situation (still less, social change) and Art (with a capital A), and even more wary of the sort of psychological claims made by Meiss in his study of painting in Florence and Siena. But architectural patronage needs money and a skilled workforce.

Even if the elite may have continued to enjoy the former, the diminution of the latter was beyond its control. The discussion of the issue, and of the emergence of the Perpendicular, in the closing pages of the book encourages the hope that, just as the ending of Becket’s Crown flagged up a possibility of a study of the arts of the 14th century, this may be signalling a future study of the long 15th century.

Rosemary Horrox is a Fellow of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, and has published widely on late-Medieval political culture and society, including the Black Death

Gothic Wonder: Art, Artifice and the Decorated Style, 1290-1350

Paul Binski

Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre, 448pp, £40 (hb)