Lying on her deathbed in Taos, New Mexico, in December 2004, Agnes Martin summoned her friend, the art dealer Arne Glimcher. “There are three new paintings in the studio”, the 92-year-old abstract artist whispered to Glimcher: “the one on the wall is finished”, she explained, “the two on the floor need to be destroyed.” “This was”, Glimcher recalls, “her last request”. The history of art is as much the history of concealment as it is the story of creative divulgence.

For many observers of Martin’s work, however, these divergent impulses—the urge to suppress and the desire to express—are difficult to disentangle even from the surface of surviving works, where veiling and unveiling seem forever to approximate each other. So enigmatically austere are the majority of Martin’s paintings and drawings that inevitably one scrabbles to find a way inside her hermetic matrix, to seize upon a telling metaphor or narrative that can help decode her work’s inscrutable encryptions.

For many, the easiest access to Martin’s achievement is by way of her mental illness and her lifelong bouts with schizophrenia. Admittedly, anguish is a compelling lens through which to bring into focus the tight meshes and painstaking grids for which the Canadian-born US abstract artist is best known. Once foregrounded in our perception of the painter’s dilute palette and her curious compulsion to adhere to canvases of static proportions (whether 12, 60 or 72 inches square), the strict ascetic restrictions placed by Martin on her own mind and practice conveniently offer themselves as crutches on which we can convince ourselves she desperately leaned: the controllable axes against which she attempted to plot her universe and to keep the chaos of her consciousness together. It is tempting, in other words, to read the art of Agnes Martin as essentially diagnostic of a patient’s suffering, symptomatic and clinical.

A revelatory retrospective of her work at Tate Modern, London, however, brings to light an alternative reality. Consisting of nearly a dozen rooms and over 100 works, the exhibition is not only the first major show of Martin’s art since her death 11 years ago, it is the broadest and most comprehensive ever staged. Its cumulative impact is to introduce, as if for the first time, a vision that everywhere succeeds in transcending the traumas and confusions of this world.

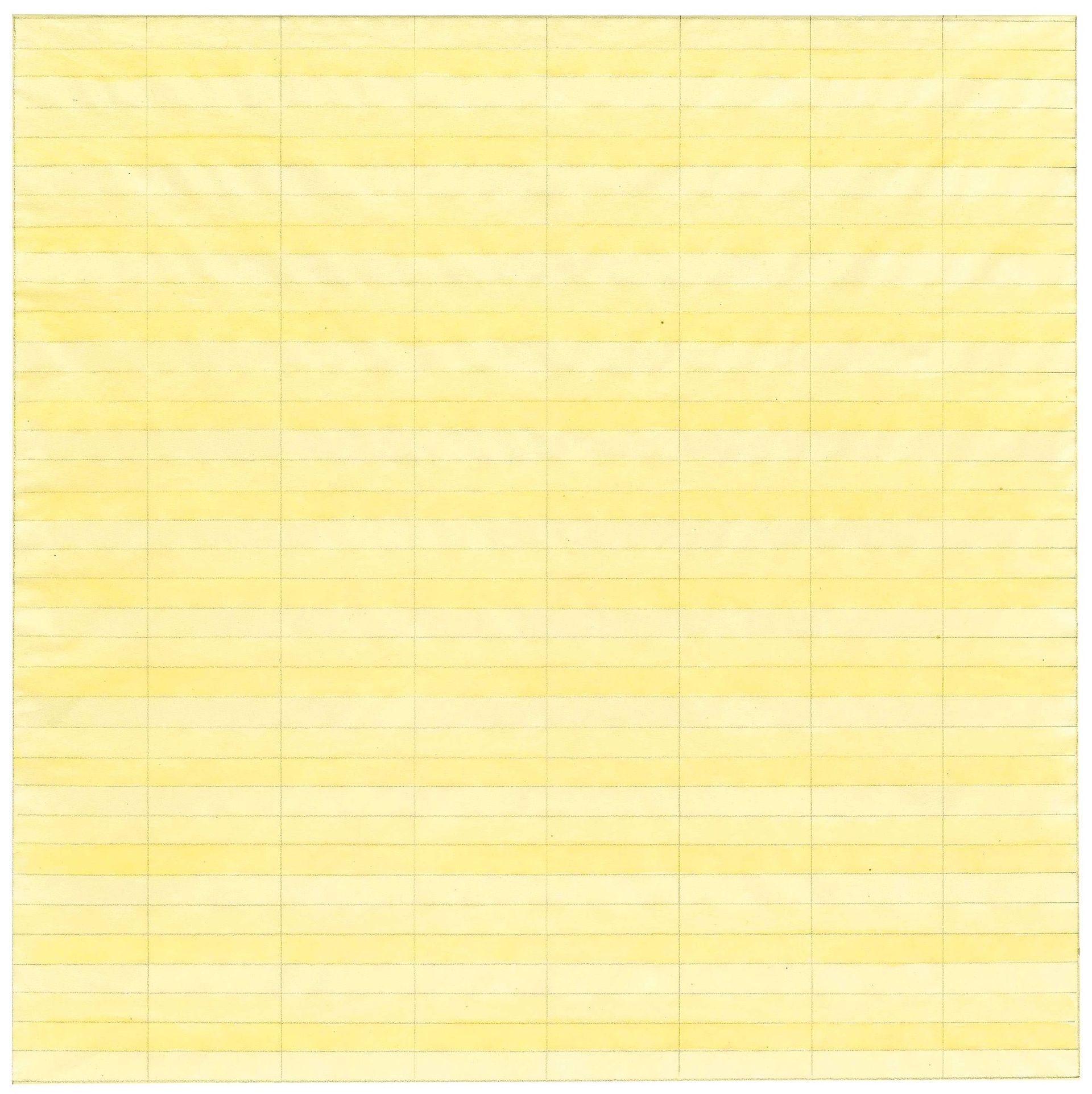

Ghosting among these diaphanous canvases, room by room, one’s eyes are slowly heightened to the uplifting paradox that undergirds Martin’s artistic conviction: apprehension of life’s beauty and its intensities does not require a retinal mimicry of physical forms in the here-and-now, but a luminous distillation of invisible harmonies and mysterious proportions. Though they may have required for their exacting execution the fragility of a mind as brittle and punctilious as Martin’s, the power of her paintings is that of a sublime symphony: their mute melodies as meticulously wrought as they are effortlessly imbibed by the ear of the eye. “Beauty is the mystery of life”, Martin wrote in 1989, “it is not just in the eye. It is in the mind. It is our positive response to life.”

That sense of ceaseless affirmation, of an endless “yes” respiring from the wall, is detectable from the first room of the Tate show, which is intended to ease visitors into the troubled tranquility of Martin’s mindscapes by way of a clutch of five large square paintings from the mid-1990s to 2000. The cool composure of Untitled 10 (1995), for example, comprised simply of seven hazy horizontal blue and pale pink stripes of equal width, is gently jostled into visual verve by the tender imperfections of the thin graphite lines that the artist has drawn by hand between each band and by the measured turbulence of her brush within each gesturally colored field. The result is a work that is lyrically disordered in its orderliness, one that unexpectedly summons as anecdotal analogy for its sinuous discipline not the episodes of psychological distress to which Martin was tragically prone, but something inherently freer and more freeing. As a young woman (long before she determined, at the age of 30, to pursue a career in art), Martin distinguished herself as a talented swimmer and in 1928 qualified for the Canadian Olympic aquatics team. Undertaken nearly seventy years later, Untitled 10 still vibrates with a careful cadence of space and stroke, of a body gliding back and forth gracefully through the resplendent density of what it is to be alive in the world.

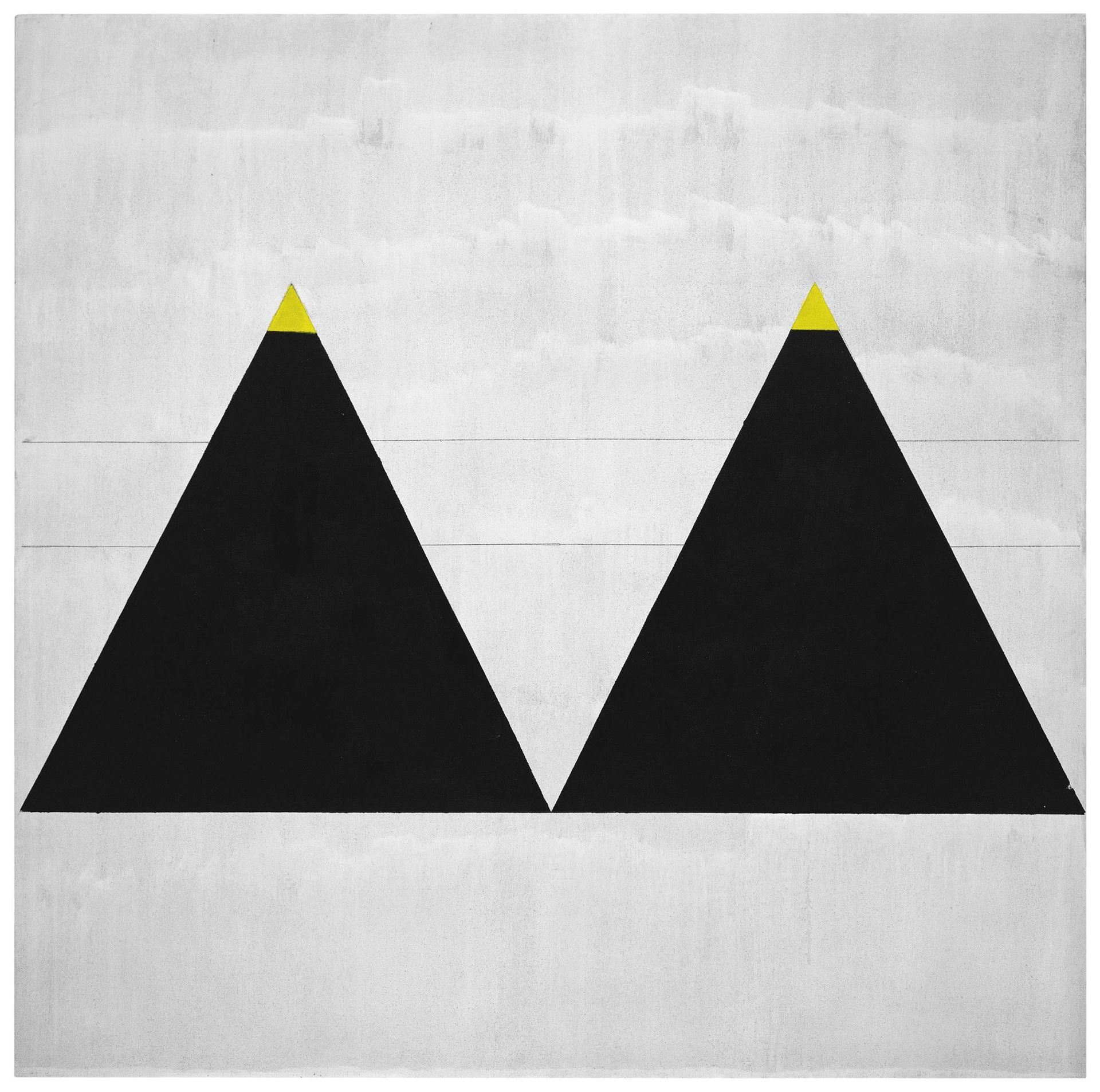

Whetted, the visitor’s appetite is thereby primed for the curatorial logic of the floor-plan that unfolds, which, beginning with the second room, follows a mainly chronological structure, taking us from Martin’s early experimentations with cubism and surrealism in the 1950s (the subject of room 2), to the gradual emergence of geometry as an enticing grammar for articulating life’s mysteries (discernible in the works collected in room 3), to the full flowering of purified form that preoccupies the interest of every other room in the show. If, in this observer’s eye, there is a key work on which to meditate in the slow toppling over of one style into another as the artist’s vision gradually falls into place, it is the yard-high oil-on-paper painting Dominoes (1960) (in room 3), undertaken while Martin was living in a sailmaker’s loft in Coenties Slip in lower Manhattan, among a cross-pollenating hive of artists that included Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Configured with seemingly indecipherable symbolism and flanked above and below by two large cinnamon spheres, a tight table of 98 domino tiles (or exactly three and a half sets) is packed into a square grid at the centre of the slender painting. Arranged with apparent haphazardness, as if freshly dealt by an unseen hand, the tiles invite a restlessness of seeing to organize their runic unruliness into meaning and order.

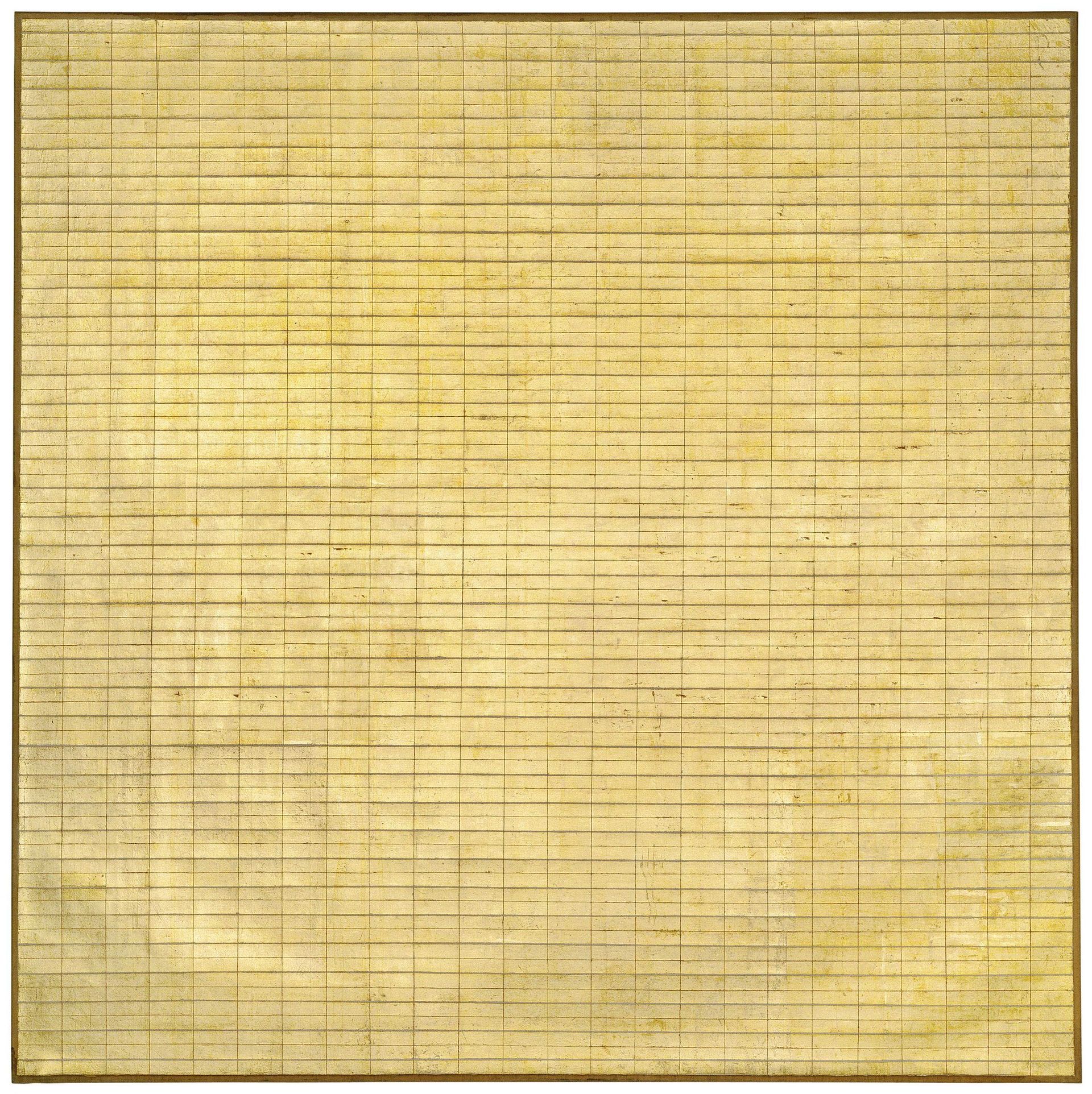

Among the first grids ever created by Martin, Dominoes is prescient with the emphases of the decades that will follow: ever-evolving schema and blueprints that are at once as entropic and precise as genetic codes. “When I first made a grid”, Martin would explain in 1989, “I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees and then this grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence.”

The works that follow on from Dominoes in the ensuing rooms of the exhibition appear to replicate with almost exponential geometric intricacy and exigency, as if the product of a self-generating equation, or the obsessive jottings of a savant compelled to prove a theorem for innocence itself. Though visitors may seek to understand the evolution of the artist’s work and the subtle adjustments in her style by way of key moments in her biography, such as her decision in 1968 to relocate from New York to New Mexico (where she’d studied art 20 years earlier), one increasingly senses that the variations in her work are calibrated less to the vicissitudes of this world than to fluctuations in the eternal music she strained to hear vibrating from another.

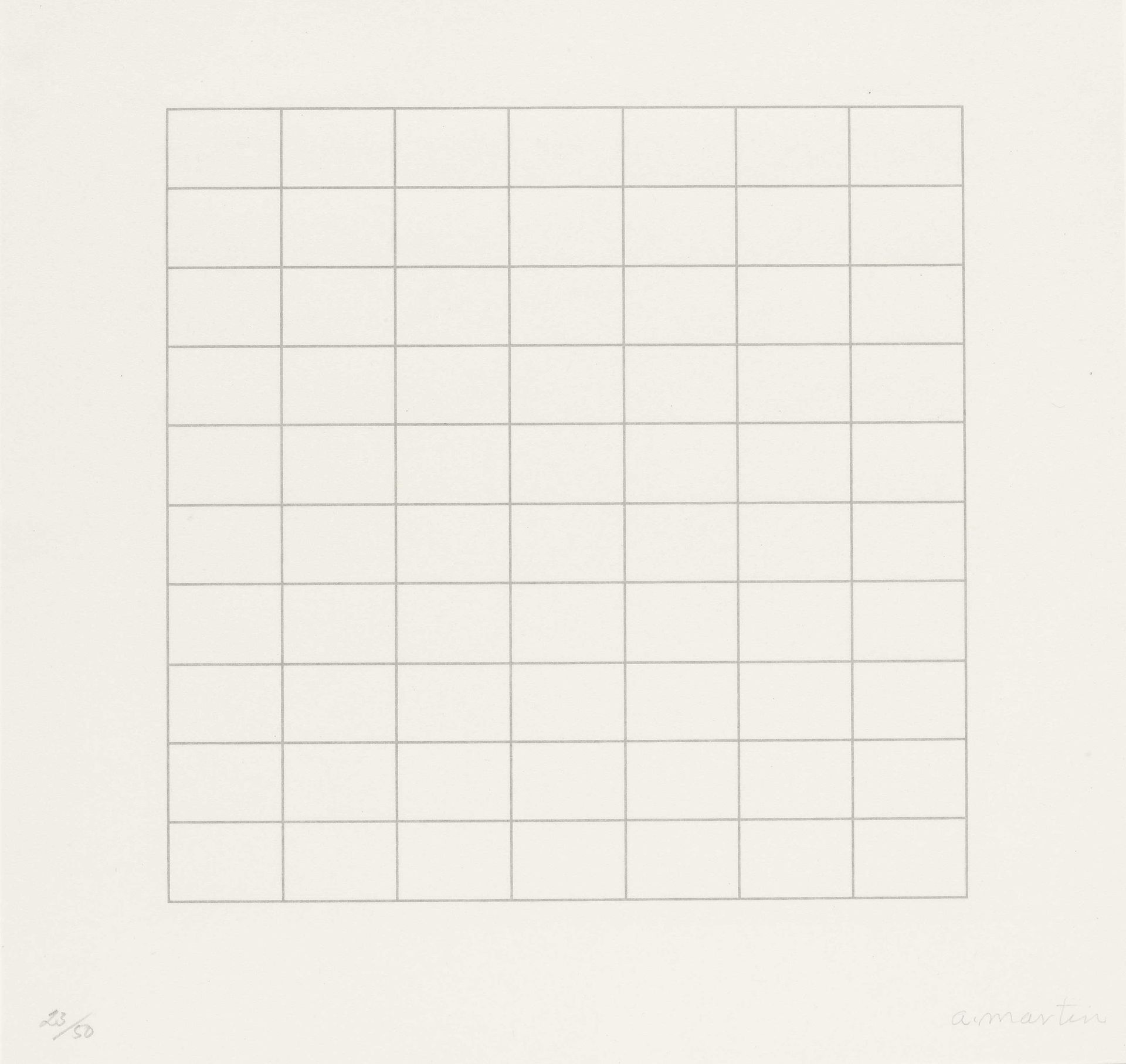

Working at the same instant that a contemporary, the painter Philip Guston, was busy abandoning the grammar of abstraction for its alleged aloofness to the realities of racial inequality in America and countercultural resistance to the war in Vietnam, Martin resolved to double-down on the restorative power and rippling rhythms of pure abstraction. In 1973, she emerged from a five-year hiatus from creating art with one of the sparest and most moving sequences in the exhibition: On a Clear Day, a 30-part portfolio of screenprints consisting of nothing more than grey lines delineating the simplest of empty tables, open lattices and undefiled grids. These existential trellises shudder from their pure white surfaces like hollow ledgers in which we are invited to balance who we are against who we wanted to be. “Like music,” Martin said in relation to the poetic purity of these works, “abstract art is thematic. It holds meaning for us that is beyond expression in words.”

Kelly Grovier is a poet and art critic. His new survey, Art Since 1989, will be published in November as part of Thames & Hudson's World of Art series.

Agnes Martin, Tate Modern, London, until 11 October