The Schaulager—founded primarily to store the Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation’s (EHF) collection—has become one of Basel’s leading contemporary art institutions. A selection of the foundation’s treasures is now on display in the exhibition Future Present, which opened on 13 June (until 31 January 2016).

Many of the works might seem familiar: since 1940 the EHF has been integral to Basel’s public art collection. Its creator—Maja Hoffmann-Stehlin (later Maja Sacher)—decided to lend its works on a permanent basis to the Kunstmuseum Basel, which is now closed for expansion, paving the way for the Schaulager show.

Presenting around 300 of the collection’s 1,000 pieces together, hung chronologically, offers a rare insight into the historical context of works from the 1920s to the present, bought because they were “forward-looking and not generally understood [in] their own time”, according to the 1933 Deeds of the Foundation.

“For a foundation’s collection to be so directly connected to the public museum, its image and its consciousness is really rare,” says Beatrix Ruf, the director of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum and previously the director of the Kunsthalle Zürich. James Koch, an executive director at Hauser & Wirth (D10) who was previously the managing director of Basel’s Fondation Beyeler, describes the EHF as “a paradigm for collecting contemporary art the world over”, praising its “courage to take risks on new work by lesser-known artists.”

The last dedicated exhibition of the foundation’s works was in 1980, when it marked the opening of the Kunstmuseum’s contemporary branch, the Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Basel (the EHF and the Hoffmann family were major contributors to its building costs).

Cough syrup meets sculpture

The collection has grown thanks to three generations of visionary women whose lives seem dominated as much by great family wealth as by personal tragedies. Its roots can be traced back to 1921, when a pharmaceuticals executive and heir married a sculptor from a family of renowned Basel architects.

Emanuel Hoffmann was the son of Fritz Hoffmann-La Roche, who in 1896 had founded the now global pharmaceuticals powerhouse, which has its headquarters in Basel. One of its first successful products was Sirolin, an orange-flavoured cough-syrup that was sold for more than 60 years; today Roche’s products include Tamiflu, Herceptin (a breast-cancer treatment) and Valium. Hoffmann’s heirs control at least half of the voting rights of a company now worth SFr240bn ($250bn) and which, according to Bloomberg, has created at least 12 Swiss and German billionaires (something on which the Hoffmann family has never commented).

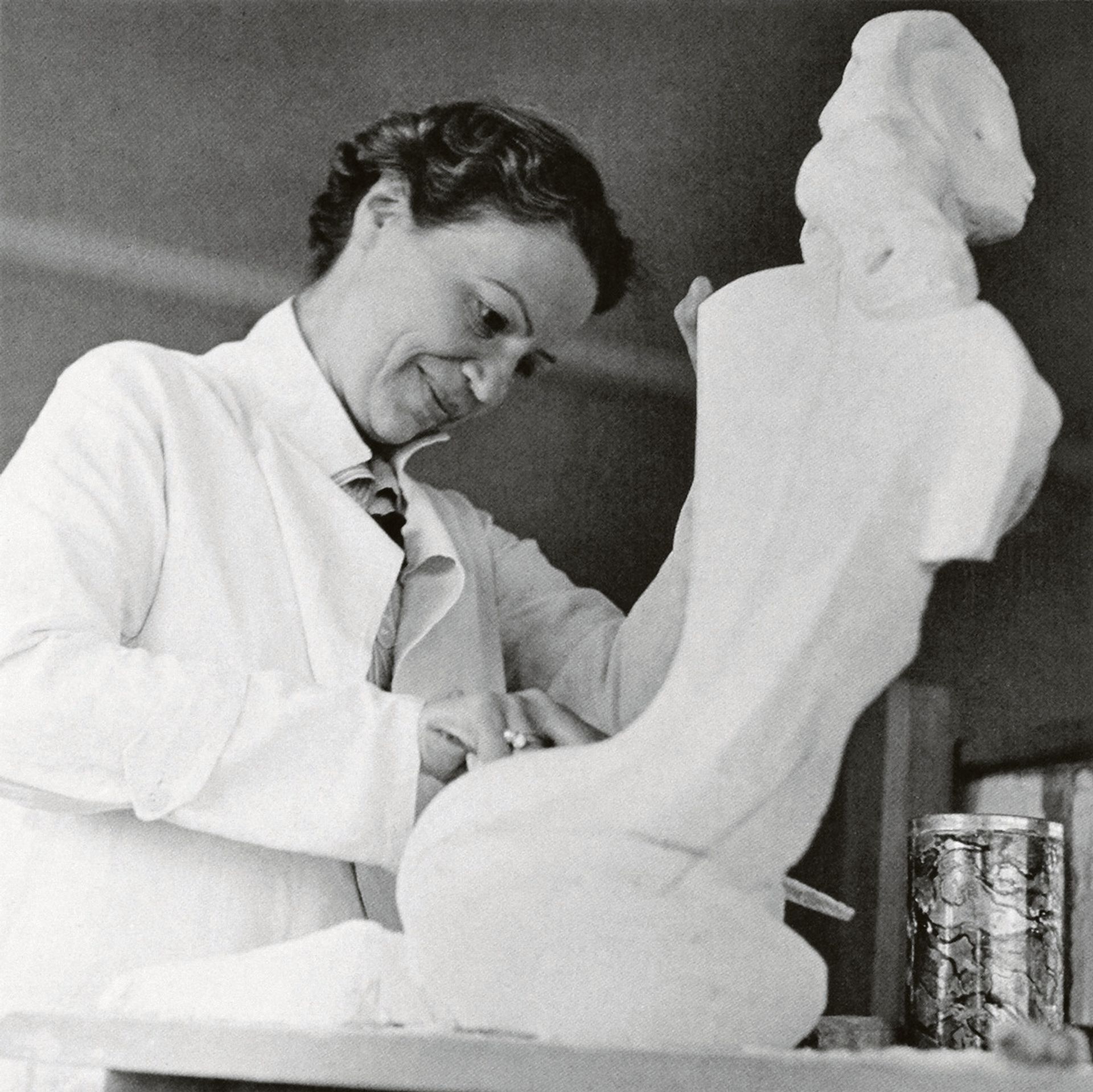

Between 1921 and 1925 Emanuel Hoffmann worked at Hoffmann-La Roche, including as the head of its business in Brussels, during which time he married Maja Stehlin. Maja Oeri, Stehlin’s granddaughter and the president of the EHF since 1991, told the art historian Catherine Hürzeler that her grandmother wanted to be an architect, but “this was not a career option for women at the time”. (The interview has been published to accompany the Schaulager exhibition.) Stehlin opted to study sculpture instead. When she and Emanuel moved briefly to Brussels, they developed a passion for art by local living artists, encouraged by their art-dealing neighbour, Walter Schwarzenberg.

Thus, the earliest pieces in the collection, and in the Schaulager show, are those by Flemish expressionists—perhaps the least compelling in terms of Modern art history, but setting a marker for the foundation’s intentions and identity. Family tragedies

The untimely death of Emanuel Hoffmann in a road accident in Basel (at the age of 36) was the first tragedy that punctuates the history of the collection. A year later, in 1933, Maja Hoffmann-Stehlin founded the EHF, establishing (and regularly topping up) an endowment fund and donating works to it from a then small, but significant, private collection.

At this time, these included pieces by Marc Chagall, Hans Arp and Max Ernst, all artists who—particularly among the conservative, bourgeois circles in which she and her late husband mixed—were largely dismissed. The Deeds of the Foundation, drawn up in 1933, not only specifies that its aim is to buy forward-looking, adventurous works, but also that they should be made “publicly visible”—and the foundation is set up so that no piece can be sold.

To have such an optimistic, committed vision when widowed with three children (her eldest child Andreas died from leukaemia just a year later) and to maintain it on the brink of a Second World War seems extraordinary, says Heidi Naef, a senior curator at the Schaulager, who organised the show.

A force to be reckoned with

Hoffmann-Stehlin (who became Maja Sacher in 1934 when she remarried) was a powerful president, reigning supreme in the role until 1979 (she died in 1989). Maja Oeri shows a great admiration for—and affiliation with—her grandmother, but describes her as “forceful”, adding that she “had the final say in any crucial decisions” about which works to buy.

This enabled a daring taste to rule, however, to the advantage of the collection. Come the 1960s, Sacher began to look beyond Europe and towards the US, when it emerged after the war as a centre of contemporary art. Thus, while also buying works by, for example, Switzerland’s then-experimental artists (Dieter Roth and Jean Tinguely), Sacher added those by Fred Sandback and Richard Tuttle, whose work she bought at Harald Szeemann’s ground-breaking exhibition, When Attitudes Become Form, at the Kunsthalle in Bern in 1969.

In 1979, Sacher handed the presidency over to her daughter, Vera Oeri-Hoffmann. The presidency, says Maja Oeri, “caught my mother completely unaware… she accepted it out of a sense of duty more than anything else.” She characterises this phase as a period of consolidation, when choosing pieces for the collection became a more democratic process between the board’s members, though not necessarily to the advantage of the collection. She credits her mother with some very important decisions, however, including the appointment, in 1982, of Jean-Christophe Ammann, the then director of the Kunsthalle Basel, to the EHF’s board.

Other major projects during this time included the founding of the Museum für Gegenwartskunst and, in 1991, a catalogue of all the works in the foundation. An updated catalogue has been produced to coincide with the Schaulager exhibition—“the collection has somewhat grown since 1991,” says Naef—including a full list of works in the collection and biographies of all the artists that it represents (around 160).

A grand-daughter’s passion

The third and ongoing phase of the foundation rests with Maja Oeri, its president since 1991, who seems to have inherited her grandmother’s passion, focus—and characteristic Swiss modesty. Stefan von Bartha, whose Modern and contemporary art gallery Von Bartha (H13) has been in Basel since 1970, says of her: “She doesn’t accept anything that is not the best and her personality is behind a single-minded and strong institution [the Schaulager, which opened in 2003]. Her influence is sometimes underestimated, because she operates largely behind the scenes, but without her, the art world would suffer a lot.”

Oeri began to formulate her plans for the Schaulager, a “viewing warehouse”, as early as 1998. She was aware that when the EHF’s works were not on display in Basel’s museums, they were in storage, and inaccessible. Her solution was to have a museum-sized space for works that were not always on public display, but were available for research and ongoing conservation. “The idea to enable scholarly research by making a collection more accessible is exceptional,” Beatrix Ruf says, describing the Schaulager as “a role model”.

To finance the new concept—and its Herzog & de Meuron-designed building—Oeri created the Laurenz Foundation, which was named after her first child, who died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in 1991. Like her grandmother nearly 60 years previously, Oeri began running the foundation at a time of great personal grief.

The environment in which Oeri has to buy contemporary art is extremely different, however. Rather than being shunned, the art of today is very much in vogue and the challenge is to keep collecting carefully, slowly and thoughtfully when big-budget buyers are willing to snap up works at a moment’s notice.

Close contact with the artists remains core. So, just as her grandmother had been friends with Roth and Tinguely, Oeri now counts Katharina Fritsch and Ilya Kabakov among her close circle. Bruce Nauman, whom Oeri refers to as “an exception in every respect”, has been collected by all three generations consistently. James Koch says that building these lasting relationships is “a key to the success” of the foundation, while Naef adds that it is particularly important in today’s “hectic environment.”

The Luma Foundation

Maja Oeri is not to be confused with her equally energetic cousin, Maja Hoffmann, who is the vice-president of the Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation and describes the exhibition at the Schaulager as “long overdue”. Hoffmann, however, founded a separate entity, the Luma Foundation, in 2004, partly, she says, because “I wanted to work with artists who were not necessarily included in the Emanuel Hoffmann collection or institutions around the world.”

The Luma Foundation works internationally to create collaborations between artists and international institutions. The major part of her work, however, is in Arles, in the South of France, where she grew up. Here she is behind a €100m project (Luma Arles) to turn 15 acres in the Parc des Ateliers site into a interdisciplinary “art campus”, at the centre of which will be an Arts Resource Center, designed by Frank Gehry (the campus is due to be complete in 2018). Exhibitions are already underway in the Parc, backed by the Luma Foundation, with shows of Tony Oursler and Janet Cardiff due this summer (6 July-20 September).

Maja Hoffmann has many other projects within Arles—she owns three hotels and a nearby restaurant—but bats off accusations that she has too many interests in the town. Her presence can also be felt elsewh ere. She is a trustee of the Tate in London and a board member of New York’s New Museum. Earlier this month, the New York-based Swiss Institute elected her as chairman of its board (effective June 2016). This week works from her collection are included in the Pool programme exhibition at the Löwenbräu in Zürich (A Blind Man in His Garden, until 27 September). M.G.