Race relations in America are at perhaps their tensest point since the Civil Rights Act was passed 50 years ago, following a string of deaths of young African Americans due to use of force by law enforcement. While these events have led to protests across the country and calls for police reform, they have also inspired many artists to react. “It is a reality that cannot be ignored, certainly not by black artists, nor by society at large”, says Katerina Gregos the curator of the Belgian pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale (until 22 November), which explores the legacy of colonialism and includes a large-scale work by the African American artist Adam Pendleton that incorporates the powerful protest slogan “Black Lives Matter”.

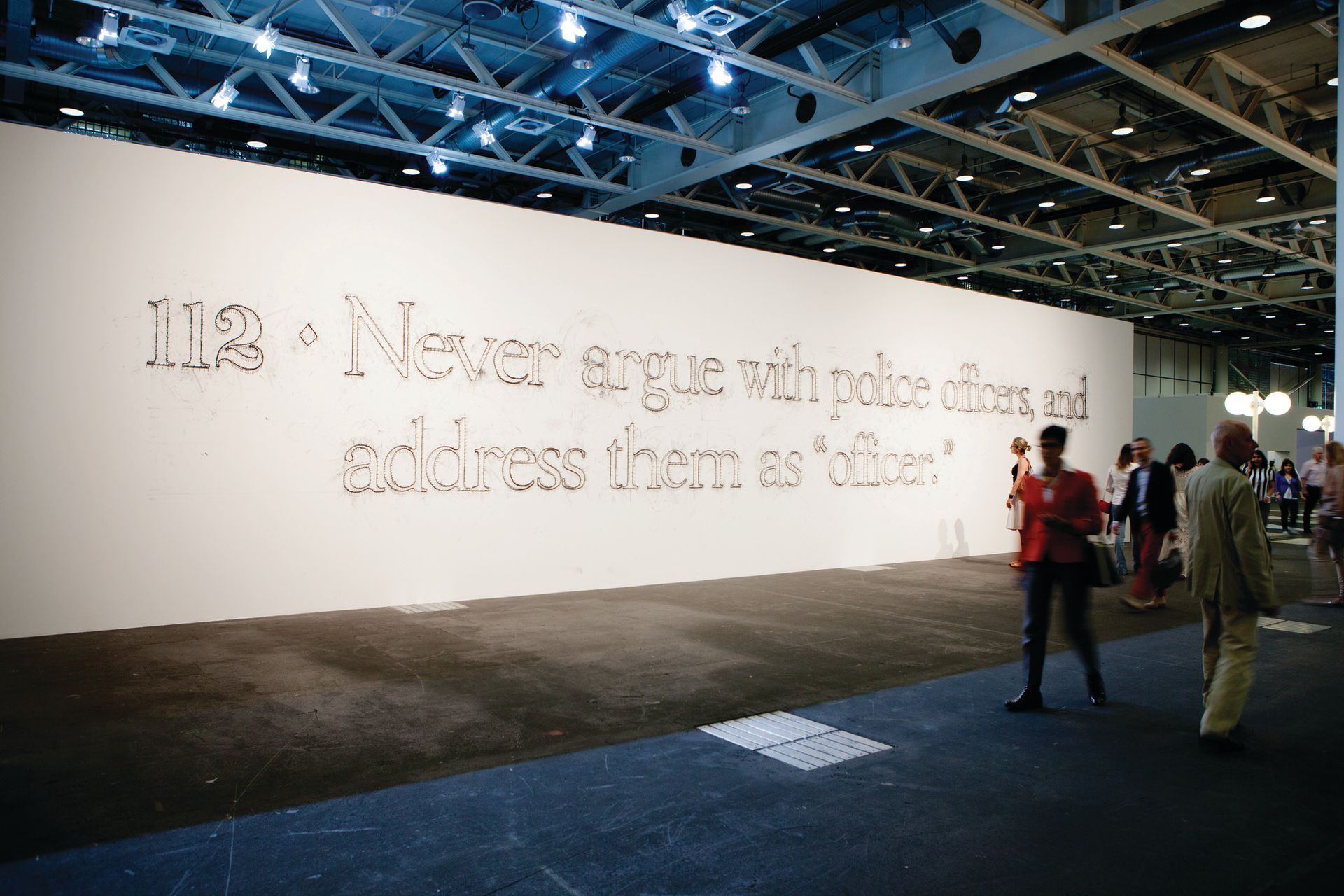

Such socially engaged works are not traditionally big sellers, and so dealers rarely bring them to fairs, but visitors to Art Basel this week have seen more works dealing with racial politics than ever before, by artists such as Glenn Ligon at Luhring Augustine (A2), Carrie Mae Weems at Jack Shainman Gallery (T6), Tony Lewis at Massimo De Carlo (R3) and in Unlimited (U6), Melvin Edwards at Stephen Friedman (L11), David Hammons at Salon 94 (J9), Lorna Simpson (also showing in Unlimited, U23) and Mickalene Thomas at Galerie Nathalie Obadia (K17), Kara Walker at Sikemma Jenkins (R11) and Victoria Miro (R7), and Adam Pendleton at Pace Gallery (A6).

Although there was “already a waiting list” for Pendleton’s works when the artist joined Pace Gallery in 2012, says its president Marc Glimcher, his participation in the Belgian pavilion has hugely increased the demand for his output. Before the fair opened, Pace sold Mississippi #2 (2015), which uses an image by the American Civil Rights photographer Charles Moore, to a British private collector for an undisclosed price. Pendleton says he used the 1960s picture in his work to “link the past to the present within our current political climate”. Another work, Black Lives Matter #1 (2015), sold to a European collector during the VIP opening. Pendleton describes the phrase emblazoned across the piece as a “public warning, a rallying cry and a poetic plea”.

Stephen Friedman Gallery has sold all five pieces it brought from Melvin Edwards’ abstract sculptural series, Lynch Fragments. Edwards began creating the works at a time of renewed racial tension in the 1960s, using objects such as chains and tools to evoke the memory of the victims of lynchings in the US. He returned to the series in the 1970s to reflect his activism during the Vietnam War, and continues to add to it today. A spokeswoman for the gallery says that Edwards has had “consistent museum presence” throughout his career, but a show at the Nasher Sculpture Center and his participation in the Venice Biennale have helped the market to rediscover his work.

Institutional recognition International institutions have been taking note: many socially engaged African American artists have had prominent museum exhibitions in the past two years including Glenn Ligon (Camden Arts Centre), Carrie Mae Weems (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation), Melvin Edwards (Nasher Sculpture Centre), and the late Jacob Lawrence (Museum of Modern Art New York).

The Broad, a museum founded by the Los Angeles-based collectors Eli and Edythe Broad, which is scheduled to open on 20 September, recently announced its acquisition of Robert Longo’s Untitled (Ferguson Police August 13, 2014), a large drawing of police holding back protesters in Ferguson, Missouri. Jonathan Jones, the Guardian newspaper’s art critic, described it as the work that “mattered the most” in 2014.

Weems, whose retrospective ended its national tour at the Guggenheim in New York last year and who was awarded a $500,000 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 2013, says that “social justice and how to articulate it at any given moment” has always been the primary concern of her work. “The urgency has been there for a very long time, but I think it’s now reaching an apex. Something has been triggered; something has been broken. Police departments around the country are having to rethink how they operate,” she says about the recent uprisings.

Jack Shainman, whose stand is dedicated to the artist, says that Weems’s retrospective provided “the perfect time to expand her audience to Europe”. At the fair, he sold the work House/Field/Yard/Kitchen (1995-96) during the VIP opening and five works from her Kitchen Table (1990) series to a major US institution.

Artists take to the streets The social efforts of many artists extend beyond the gallery. In 2011, Weems launched Operation Activate, a public art campaign in Syracuse, New York, to raise awareness about gun violence. This led her to open the Institute of Sound and Style, a summer programme that provides visual arts training for underprivileged youth. Weems is now working with artists and urban planners to expand the institute to cities across the country.

“It is a natural step,” Weems says. “I’m a person who is engaged in my community. My work grows out of that space, so it’s only natural that I would step up to the plate given the opportunity to help bring the arts back to the community.”

In Los Angeles, Mark Bradford founded the Art and Practice Foundation, which offers jobs to foster children and stages contemporary art exhibitions by black artists. Other artists, such as Rick Lowe (another MacArthur award winner) and Theaster Gates, have extended their art practice to encompass the restoration of dilapidated buildings in their local neighbourhoods.

Despite such productivity, Gregos points out that it is important to remember that there are still “far fewer black artists (as well as women artists) who are widely recognised for their work and represented at the top end of the art market,” she says. “In that sense, there is still a long way to go towards racial and gender equality in the art world.”