Joseph Beuys, striding towards the camera, wearing a hat, boots and with bag slung over his shoulder, has become a defining image of the German artist. The portrait La Rivoluzione Siamo Noi (We Are the Revolution, 1972) owes much to a tradition of charismatic reformers, many with something of a messiah complex. It is this tradition that Artists and Prophets: a Secret History of Modern Art chronicles.

The publication lives up to its title, revealing in rich and often entertaining detail the men in whose footsteps artists as diverse as Beuys, Egon Schiele, František Kupka and Hundertwasser followed. Co-written by Pamela Kort and Max Hollein, the director of the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, it accompanies the exhibition of the same title, which closed in Frankfurt on 14 June. It travels next month to the National Gallery Prague (22 July-18 October).

Vegetarian nudist

Five prophets, starting with Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, who exposed the benefits of vegetarianism and nudity, are singled out. All are from the Germanic-speaking world of the late 19th and early 20th century.

An artist-prophet, Diefenbach spread a gospel of a more “natural” lifestyle, while going barefoot and being embroiled in a battle with his ex-wife for custody of their child. He was charged at various times with disorderly conduct (for working naked) and lectures deemed immoral by the authorities; his followers were known as Diefenbachers. His long hair and Christ-like garments served to drum up attention for his art exhibitions, held in Munich and Vienna among other cities.

Diefenbach’s greatest contribution to art history was a 68-metre-long frieze, shown in Vienna in 1898. Kort convincingly argues that it helped inspire Klimt’s famous Beethoven Frieze. He ended his days on the island of Capri, leaving behind a trail of debts and lingering memories among avant-garde circles.

Beuys’s shamanism can be traced back to Diefenbach and those he inspired. In 1971 Beuys spent time in Naples and Capri, invited by the Italian art dealer Lucio Amelio, who shared an interest in the artist-prophet. There he saw a photograph of Diefenbach as a prophet, bearded and berobed, which inspired the famous image of Beuys himself, taken in Amelio’s villa.

Jörg Immendorff, Beuys’s one-time student, also owes an overlooked debt to men such as Diefenbach, the authors reveal. As a young artist Immendorff parodied the messianic aspect of Beuys’s art and persona. By 1968 he had slipped for a while into the role of prophet, championing New Age beliefs and bohemian-anarchist behaviour. He took to the streets (and to Documenta, when he was excluded from the exhibition) carrying a staff topped by a figure of a polar bear. Photographs show him to resemble the prophet and photographer Gustav Nagel, who had made a good living half a century earlier, selling postcards of himself as Jesus.

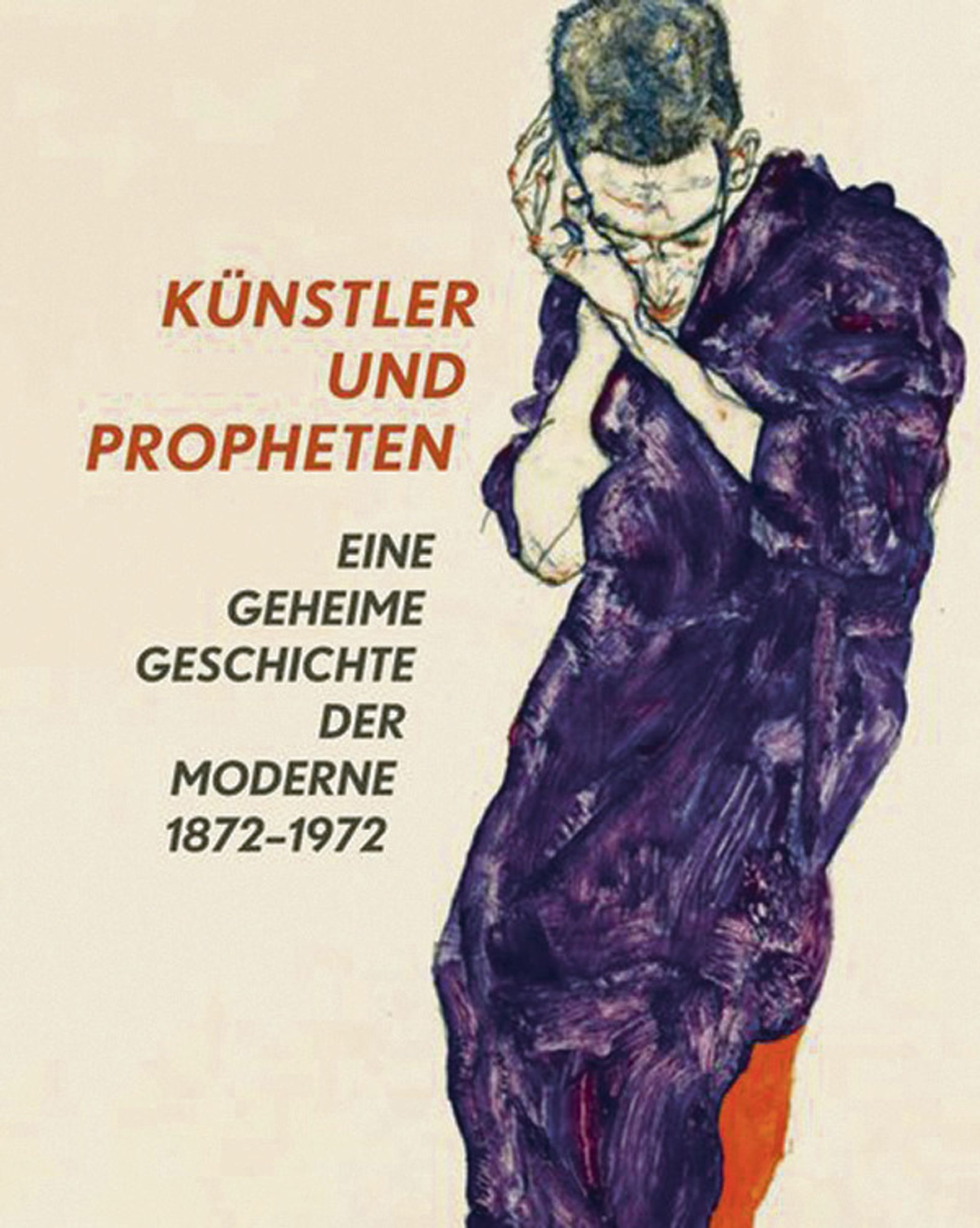

Emaciated and contorted

Schiele’s self-portraits, his body emaciated and contorted, owe a debt to the religious fervour that Diefenbach and others exploited. The young artist wrote of his yearning to join a “monk-like artistic community”. Erotically charged, these self-portraits have a strong mystical dimension, as do Schiele’s drawings and paintings of naked children. Bodies, he believed, were merely the “husk[s] of our souls”, as his friend, the art critic Arthur Roessler, wrote.

A contrast to the febrile spiritual atmosphere of Vienna in the early 20th century is provided by the Inflation Saints, who flourished briefly after the First World War, when Germany’s economy collapsed. Ludwig Christian Haeusser, a former champagne merchant, got religion on a business trip to Zurich and decided he was Christ, Tao and Zarathustra. He set up a newspaper, lectured at the Bauhaus and, while in jail, campaigned for a seat in the Reichstag (his histrionic speeches gave Adolf Hitler some ideas).

Another colourful character was the Dadaist Johannes Baader, self-declared “President of the Globe” and arguably Germany’s first media artist.

Artists and Prophets: a Secret History of Modern Art 1872-1972

Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

Snoeck, 512pp, €58 (pb)