Dasha Zhukova’s Garage Museum for Contemporary Art is due to open the doors of its new $27m home in Gorky Park to invited guests on 10 June and the public two days later. The museum is housed in a Soviet-era pavilion that has been converted by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas; an “Infinity room” by Yayoi Kusama will be among the attractions inside. Outside another installation by the 86-year-old Japanese artist, Ascension of Polka Dots on the Trees, will transform a corner of the Moscow park.

The Garage’s chief curator, Kate Fowle, says Kusama’s work resonates strongly with its mission. “A lot of the emphasis at the Garage in the last year or so has been on developing exhibitions that are more participatory,” she says. “Kusama’s work is all about connecting. It’s about psychological and immersive ways of getting involved in what she does. It is much more emotional and emotive,” and her experience as a Japanese artist working abroad in New York in the late 1960s also strikes a chord.

A space for all seasons

Koolhaas has converted Vremena Goda, a prototype, prefabricated restaurant pavilion built in Gorky Park in 1968, into the Garage’s new home—its third since 2008—all of which have an architectural pedigree. Zhukova, who is the partner of the billionaire Roman Abramovich, first unveiled a centre of contemporary art in a former 1920s Constructivist bus garage designed by Konstantin Melnikov. In 2012, the centre (now a museum) moved to a temporary home in Gorky Park designed by the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban in his signature material of cardboard.

Koolhaas, who first saw the building when he visited the Soviet Union as a young man, has maximised the space in the Vremena Goda by wrapping the concrete structure in polycarbonate skin and installing most of the museum’s technical services within the building gap. The museum’s director Anton Belov says the surviving Soviet-era decorative features, “unique tiles, mosaics and brick”, have been restored by a team of conservators from Italy.

Visitors will find a series of commissions in an atrium, juxtaposed with the pavilion’s “autumn” mosaic—the sole surviving piece marking the Four Seasons or “Vremena Goda”. The commissions begin with the Soviet Sots Art pioneer Erik Bulatov’s first large-scale work in Moscow.

A work by Louise Bourgeois, on loan from the artist’s foundation, is due be installed in September. The Chicago-born artist Rashid Johnson is creating a commission that is due to be unveiled in March 2016. He has had access to Russian archives, including one documenting a Soviet-era biennial in Africa.

Fowle says that the Garage will provide the first opportunity in Russia for international artists to create large, site-specific works.

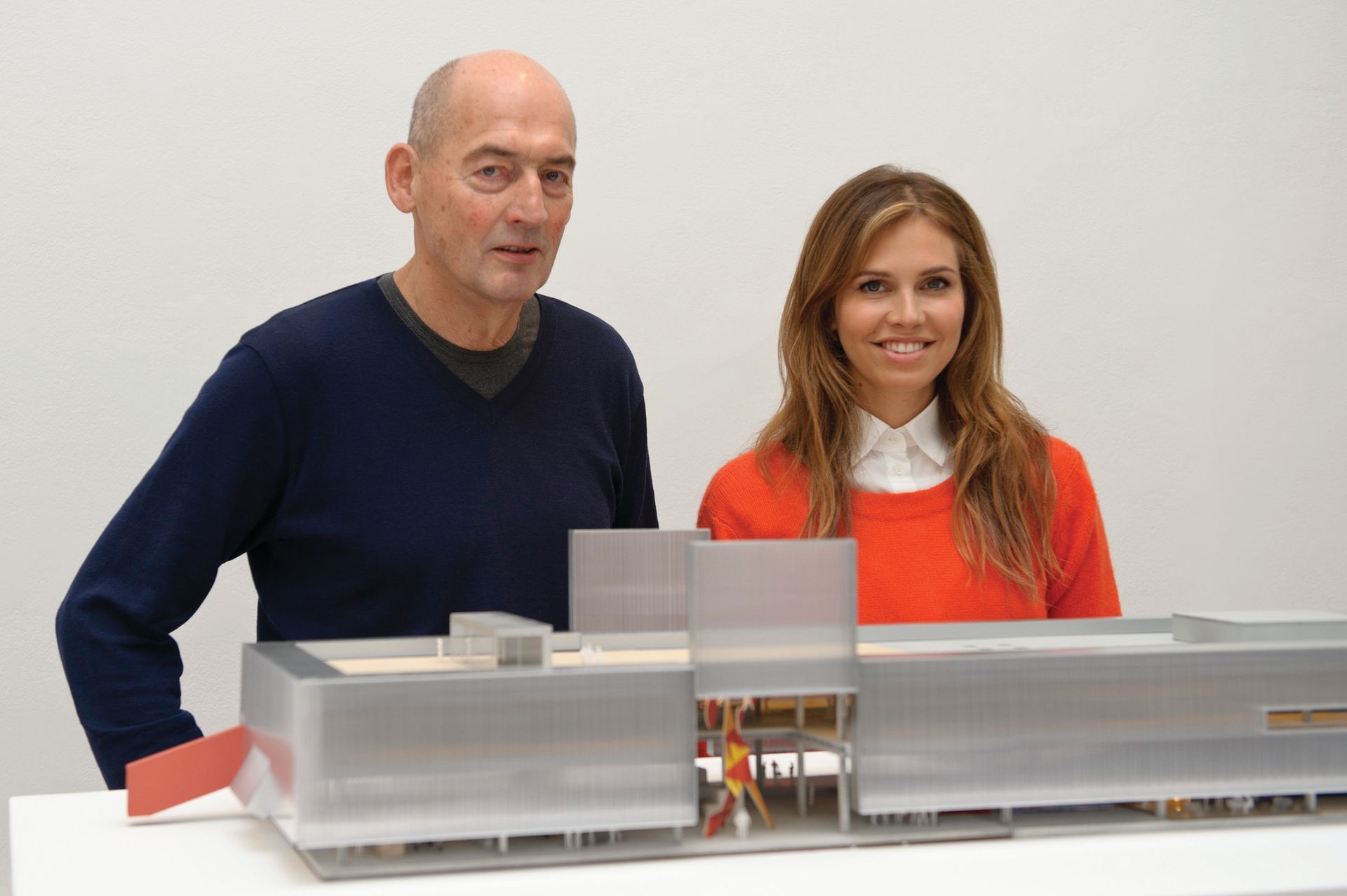

Architect Rem Koolhaas has converted a Soviet-era pavilion into a space for art and an open library for Dasha Zhukova

Archive and library too

In another riff on the building’s architecture, Garage will be hosting a conference in October on Soviet Modernism, a project of the Austrian curator Georg Schöllhammer, who joined Garage as an international adviser earlier this year. In May, the museum announced its international advisory council, which includes Michael Govan, the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Hans Ulrich Obrist, the co-director of London’s Serpentine Galleries.

The Garage is also a research archive and houses Russia’s first public contemporary art library. “The archive is the largest collection in the world devoted to the study of the processes that took place in Russian art from the middle of the 1950s to now,” Belov says. He believes that the “Garage has fundamentally changed the cultural landscape of Russia.”

The museum, which is privately funded by Zhukova’s Iris Foundation, has so far avoided run-ins with Russia’s new moral police of bureaucrats and fundamentalist Russian Orthodox activists, who protest public funding of art they deem offensive.

Given recent events in Russia, the Garage might seem to be at cross-purposes with the country’s general direction. Fowle, who was chair of the master’s programme in curatorial practice at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco and was a curator at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing after that, says that Western commentators often unfairly expect artists in countries like Russia to react instantly to the political situation. “Art is a form in which you can explore political and social issues in a way that you can’t otherwise,” she says. “I don’t think art’s function is to change politics. I think it would be naive to think that is the situation, but you can create a space for discussion, so people’s perspectives can be heard.”