The “re-performance” of past, one-time-only events that curators have dropped into recent historical exhibitions proves yet again that any road paved with good intentions is a bumpy proposition. Without the political and social temper of the time in which the originals first appeared—better communicated by existing photographic documentation—the restaging of ephemeral works for viewers who weren’t present the first time around rarely results in more than pale imitation.

Last month at Frieze New York, Frieze Projects curator Cecilia Alemani fared better than most with her “tribute” to the Flux-Labyrinth. An immersive environment dating to 1976, it was virtually unknown even to viewers familiar with Fluxus, the groundbreaking group of Neo-Dadaists founded in New York in the early 1960s by the Lithuanian-born visionary George Maciunas.

At the fair, people steadily queued for entry to the labyrinth, puzzling through trick doors dividing the obstacle-strewn cubicles of a narrow, snaking 200 ft-long corridor. They walked on marbles, mounted steps that threatened to bounce them off, stepped over beachball-size balloons and squeezed through a gauntlet of sweaty, human flesh. Few knew what they were missing.

“We had to go to the circus with a translator and ask for elephant shit. I had people blowing up balloons while we waited”

For example, fairgoers didn’t have to plunge their hands into elephant dung. The pachydermic poop was the pièce de résistance of the first Flux-Labyrinth, a noisy, smelly, teasing test of nerves designed by Maciunas and his protégé Larry Miller for New York, Downtown Manhattan, SoHo, a 1976 show produced by the German dealer René Block for Berlin’s Akademie der Künste.

Liberation from pomposity Maciunas had formed Fluxus to liberate art from pomposity and preciousness, or corruption by the art market. With such artists as Yoko Ono, George Brecht, Alison Knowles and Nam June Paik among his collaborators, he staged happenings and electronic music concerts, held a Flux Mass in a chapel at Rutgers University—where the group was in residence in the 1960s—and produced “Flux Boxes”, cheaply packaged assemblages of small objects, performance “scores” (instructions for live actions) and publications by affiliated artists.

As Geoffrey Hendricks, a founding member, says: “The thrust of Fluxus was to get people away from taking art too seriously. It wasn’t about individual ego, but working together on projects that may not be great art but get at the human condition and the wellspring of the creative process.” The Flux-Labyrinth animated that principle but, as documents in the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Archives at the Museum of Modern Art in New York attest, it was a long time coming.

The idea dates back to 1975, when Maciunas proposed a slapstick environment for Block’s West Broadway outpost, where it could thumb its nose at the devil—the art market. “I saw myself not as a dealer but as a curator,” Block recalls in an email. “I saw the gallery as a possibility to participate in the actual, and non-commercial, art scene.”

For various reasons, the show never came off. But Block remained keen on the idea and, a year later, he asked Maciunas to bring the labyrinth to Berlin—he bought the rights to install it for $2,000.

“I think of the Flux-Labyrinth as George’s masterstroke of a giant Flux Box,” says Miller, who worked closely with Maciunas from 1969 until his death in 1978. The two designed the labyrinth together as an obstacle course that Miller then built on-site over the course of a month, following instructions from the participating artists.

Each conceived obstacles for one playful—and often threatening—segment, as well as the doors between them. One door pivoted on a circular axis; another flipped up, forcing visitors to crawl beneath it. Ay-O, an artist associated with the Gutai group in Japan, forced labyrinth-walkers to propel themselves through a tight crevice between two pink mattresses, as if through a birth canal.

Artistic pranks The labyrinth’s entry portal had two knobs. It opened only when visitors turned both at once, triggering a large rubber ball to swing towards their heads and back like a cartoon boxing glove on a spring. That was Miller’s idea, as was a room with big balloons that predated Martin Creed’s balloon rooms by two decades. Knowles wanted doorknobs greased in face cream. That didn’t happen; nor did Maciunas’s sticky floor and a see-saw. “There was collaboration in the sense that we were realising the work of others,” Miller says, “but we had to modify it according to budget, space and availability.”

Those factors altered the labyrinth’s design on a daily basis, particularly after Ben Vautier, Brecht, Robert Watts, Hendricks and Knowles dropped out—each for a different reason. “We filled in the voids by inventing whole new ideas, or making some sections longer,” Miller recalls. “My section was a totally black space that I rugged off, so it was an entirely tactile experience, which is what George was all about. It was a box for the body.”

To get through Maciunas’s segment, recreated at Frieze, people had to cross a rubber bridge, advance by slipping their feet into raised and slanted, sandal-shaped steps and walk on marbles with only uneven railings for support. “George was a prankster,” Miller says. “He didn’t care about safety. I told him we had to have rails or people would get hurt. So I proposed that [the rails] go up and down, and he liked that.”

Maciunas also wanted people leaving the original labyrinth to feel their way through elephant dung to open the door, but maintenance workers cleaned it up every day. “We had to go to the circus with a translator and ask for elephant shit,” Miller recalls. “I had people blowing up balloons all day while we waited for more dung.”

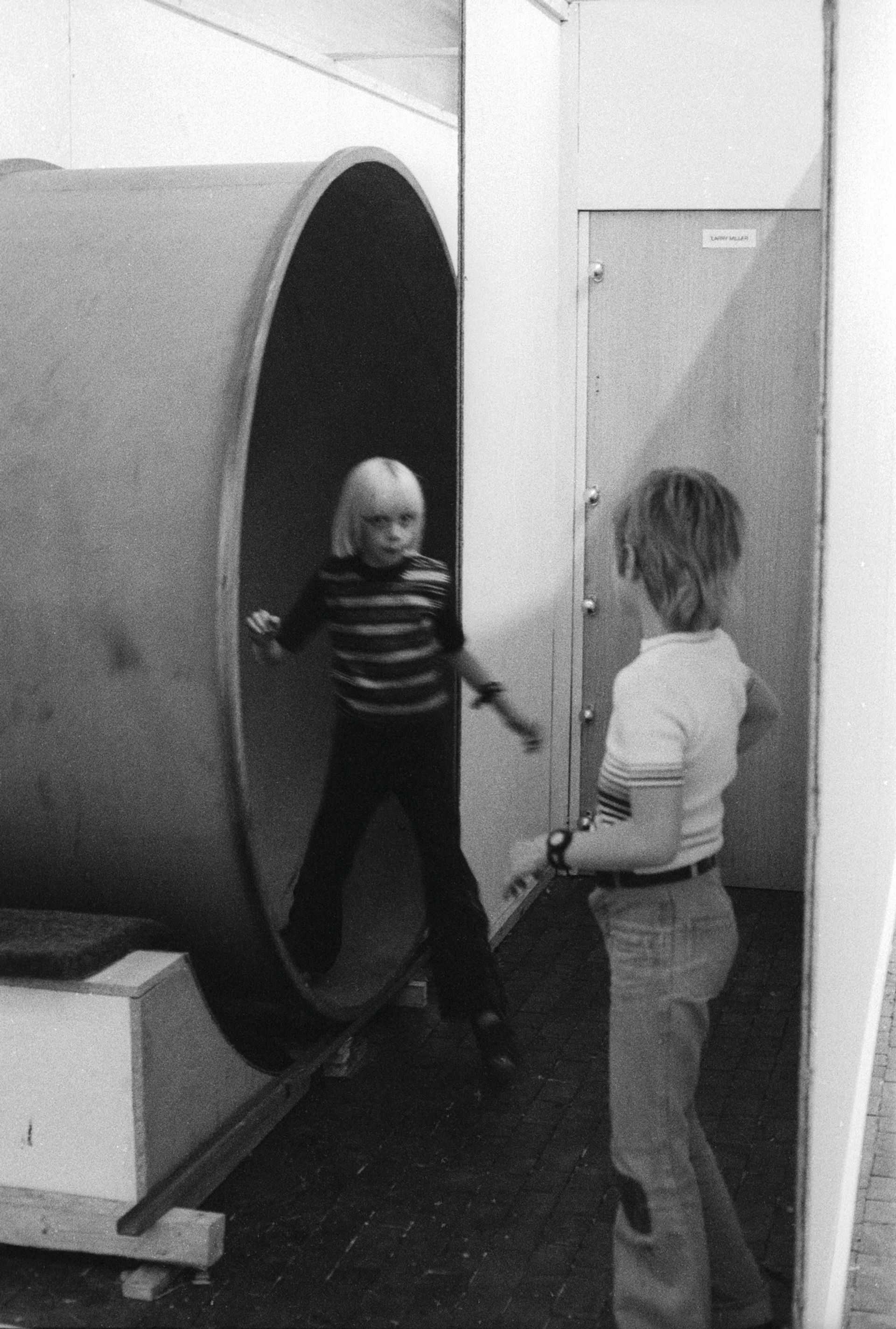

High heels forbidden Joe Jones contributed an enormous metal cylinder that rolled down the corridor on tracks as people stepped through it. Miller fitted the metal drum with noisemakers that emitted the sound of mooing cows as it rolled. “The idea,” Miller says, “was multisensory bombardment”—something that the Frieze version only partly captured.

Though it included contributions from Knowles and Hendricks reprised from a second labyrinth that Miller built in a 1993 Fluxus exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Alemani’s tribute didn’t have Jones’s drum, the swinging ball or Miller’s dark room and was missing many sound effects as well as the dung. It also lacked Maciunas’s sign, posted on the original, denying entrance to the overweight, the accident-prone, the drunk, people with wooden legs and “women or men with high heels”.

In New York, where Frieze staff gave verbal warnings and had visitors sign waivers, the labyrinth had emergency exits—anathema to Maciunas. But times have changed, along with health-and-safety regulations. Additionally, Frieze has labour contracts and when Alemani told Miller that her team would do the construction, he balked. Already sceptical of placing a Fluxus work in an art fair, he felt strongly that any restaging would be inauthentic without him. However, other commitments meant postponing for a year.

With the Maciunas estate’s permission, Alemani reluctantly went ahead without Miller, inviting Amalia Pica, John Bock and the Austrian collective Gelitin to interpret the Fluxus spirit. Gelitin’s unusually minimal contribution was an empty room with two confusing doors—not much of a challenge. Nor was Pica’s Bureaucratic Obstacle, where visitors completed a nonsense form that was shredded into a pile through which they had to walk. The idea came less from Fluxus than the Argentine-born artist’s lengthy application for UK citizenship. In Bock’s more sensory installation, people leaving the labyrinth had to squeeze between two facing lines of chanting, overweight men clad in gold lamé hotpants and vests dangling equipment that unleashed their body odour.

“My space was brutal,” Bock says. “I wanted to connect the bodies to the audience. It’s good to have this contact, and it’s necessary to bring this kind of thing to an art fair. It’s not always beautiful to buy art and everything is fine. It’s more important that humans have contact with other humans.”

Though tactile and perverse, Bock’s contribution still lacked Fluxus’s critical wit. Like the rest of the Flux-Labyrinth, it was an interpretation, not a recreation, of an idea from a less money-mad time, when visitors came in off the streets and, unlike the fair, it only cost them their dignity.