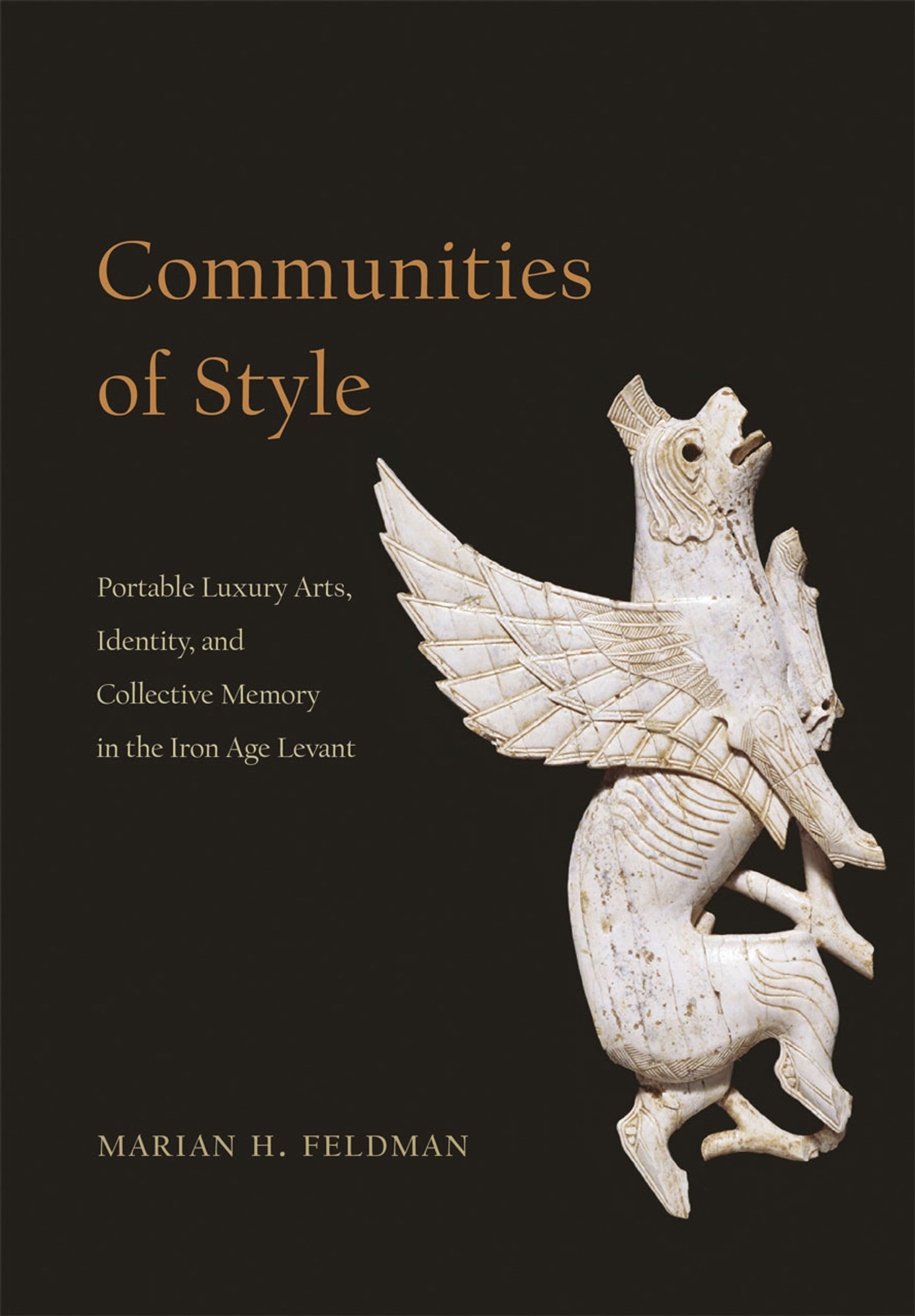

This important volume provides new approaches and interpretations for the study of ancient art. Communities of Style: Portable Luxury Arts, Identity, and Collective Memory in the Iron Age Levant explores spheres of production, elite consumption and the repurposing of works of art within the Iron Age Mediterranean and Near East. Marian H. Feldman’s book tackles thorny questions of regional attributions of craft practices in the Iron Age, a period traditionally associated with Phoenician and Greek interaction in the Mediterranean, and the expansion of the Assyrian empire and its impact on the Levant, including Israel, Judah and the Syro-Hittite kingdoms. Her focus on luxury arts offers a rich understanding of the role of two of the most common genres of objects: bronzes, which include Phoenician metal bowls known across the Mediterranean; and ivories, which include the famous groups found at Nimrud, Iraq.

This book breaks down traditional art-historical concepts of connoisseurship that connect styles with geographic origins, cultures, languages and even specific production centres. Feldman believes that the attribution of workshops to specific centres is a fruitless exercise. Although she acknowledges the rich scholarly tradition of attribution, including the well-established work of art historians including Irene Winter and Georgina Herrmann, Feldman goes on to deconstruct canonical terms such as “North Syrian” and “Phoenician” – collapsing them into a broader, more fluid “Levantine” terminology.

Feldman instead examines how stylistic practices helped constitute new elite community identities, breaking down idealised notions of Phoenician mercantilism and Assyrian imperialism that have dominated our view of production and movement of bronzes and ivories during the Iron Age. Instead, she evokes more overarching arenas of power, control and opportunism to explain the creation and circulation of these elite products. The Assyrians were possessors of foreigners and foreign art, reflected in works such as the famous Garden Party relief of Ashurbanipal and through their hoarding of enemy riches. The Assyrian court, by contrast, developed its own recognisable style which helped bolster and consolidate order and control.

Personhood and possession

Chapter four highlights the ideal of personhood and possession through inscribing names on metal drinking vessels, and the role these rare “speaking bowls” played in the consumption of wine, funerary rites and the crafting of elite identities. “The reuse, recycling and displacement of luxury art” (Chapter five) is the most interesting, highlighting the extreme mobility of objects, such as the horse trappings and other items inscribed by King Hazael of Damascus in the ninth century BC, then taken as booty or tribute from North Syria to Damascus, and ending up in places as far afield as Assyria and Greece. Feldman explores the presence of Near Eastern ivories and bronzes in Greece and Cyprus within the context of Assyrian decline and collapse (after 612 BC) through mechanisms of looting, salvage, hoarding and new elites. These explanations are offered as alternatives to Homeric-inspired Phoenician-Greek interactions that are often evoked for this East-West phenomenon. Feldman successfully adds to our interpretations of luxury arts on the move, drawing on the rich archaeological record available for some.

Feldman portrays emerging elites, such as those at Salamis, or opportunistic looters elsewh ere, as the main groups accessing such objects after traditional elites lost possession of them. But how accessible were these objects across the social spectrum during their primary circulation? In summary, this volume should have a significant impact on the way we think about ancient art. Will historians of ancient Near Eastern art stop using terms such as “Phoenician” or “North Syrian” any time soon? Probably not, but they should take note of Feldman’s thoughtful and innovative study.

Communities of Style: Portable Luxury Arts, Identity, and Collective Memory in the Iron Age Levant

Marian H. Feldman

University of Chicago Press, 264pp, $70 (hb)

John D.M. Green is the chief curator of the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago, specialising in the history, art and archaeology of the ancient Near East. He was formerly the curator of the ancient Near East at the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, specialising in the archaeology of the Southern Levant