Art about Aids is strident and quiet, hopeful and bleak. Real and surreal, cerebral and sensual, aggressively political and carefully coded, the art shaped by the initial Aids crisis of the 1980s contains the sort of multitudes celebrated by the poet Walt Whitman.

This is one way of summarising Love Letter from the War Front, a section of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s inaugural exhibition (America Is Hard to See, until 27 September, see p74-75) in its new home in New York’s Meatpacking District. Dedicated to responses to the Aids crisis, the section is named after a 1988 work by Félix González-Torres that shows a fragment of an intimate letter (further fragmented by having been printed on a jigsaw puzzle). The display includes a wallpaper-style installation of Donald Moffett’s lithograph He Kills Me (1987), in which the title is emblazoned in orange on a photograph of Ronald Reagan, who was widely criticised for ignoring the mounting Aids crisis. Next to Reagan’s face is an orange-and-black target.

Inside the gallery are wrenching photographs by other well-known artist-activists, such as Nan Goldin and David Wojnarowicz (pictures by the latter show the photographer Peter Hujar on his deathbed), who participated in “direct actions” with Act Up (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) to confront homophobia and push for the federal Food and Drug Administration to approve drugs more quickly. Yet nearby, an oddly beautiful, symmetrical canvas by the late artist Martin Wong, Big Heat (1986) shows two firefighters kissing in front of a tenement building in which the bricks are rendered in lavish detail, prompting the Whitney’s curators to call it a “utopian vision of hope, love and redemption within the crumbling environs”.

The show reflects a larger trend sweeping the US today—a growing interest in revisiting and deepening our understanding of the period in which Aids threatened to destroy the art world and also dramatically shaped it. Instead of a story of 1980s American art-making starring Neo-Expressionist bad boys like Julian Schnabel and David Salle, artists such as Moffett, Wong, Goldin, Wojnarowicz, Robert Gober and Keith Haring are becoming more central, achieving increased recognition of the sheer diversity of their work.

“It’s important not to browbeat people, but to show them the extraordinary loss that gave them their freedom”

This summer, the Pacific Design Center branch of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (LA MoCA) will address the topic in a group exhibition called Tongues Untied (6 June-13 September), which takes its name from Marlon Riggs’s 1989 erotic documentary about gay black poets. The show will include works by González-Torres and Goldin. Nearby, the West Hollywood Library will host a small preview of a sprawling travelling show called Art Aids America, which opens at the Tacoma Art Museum in Washington later this year (3 October-10 January 2016).

The J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art are working together to stage an ambitious Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective (15 March-31 July 2016), and the Whitney is due to stage a Wojnarowicz retrospective next year. Less celebrated artists who were active in the community that was so badly affected by Aids are also getting their due: this year alone, there have been exhibitions on Wong at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco, Brian Weil at the Santa Monica Museum of Art and Tseng Kwong Chi at the Grey Art Gallery at New York University.

Urgent need for reappraisal Collectively, this amounts to a reconsideration of Aids-related work, which is now being uncrated and presented with the urgency of something that had been just as vigorously repressed. It is not entirely new to see a museum show on the subject, but it is unusual to see so many, going beyond blockbuster figures like Mapplethorpe and Haring. So is it just a question of timing, given that so many art—and fashion—trends seem ripe for recycling 20 to 30 years after their most recent appearances? Certainly, the menswear designer Patrik Ervell’s spring advertising campaign, featuring portraits by Hujar, makes the once-underground work seem rather trendy.

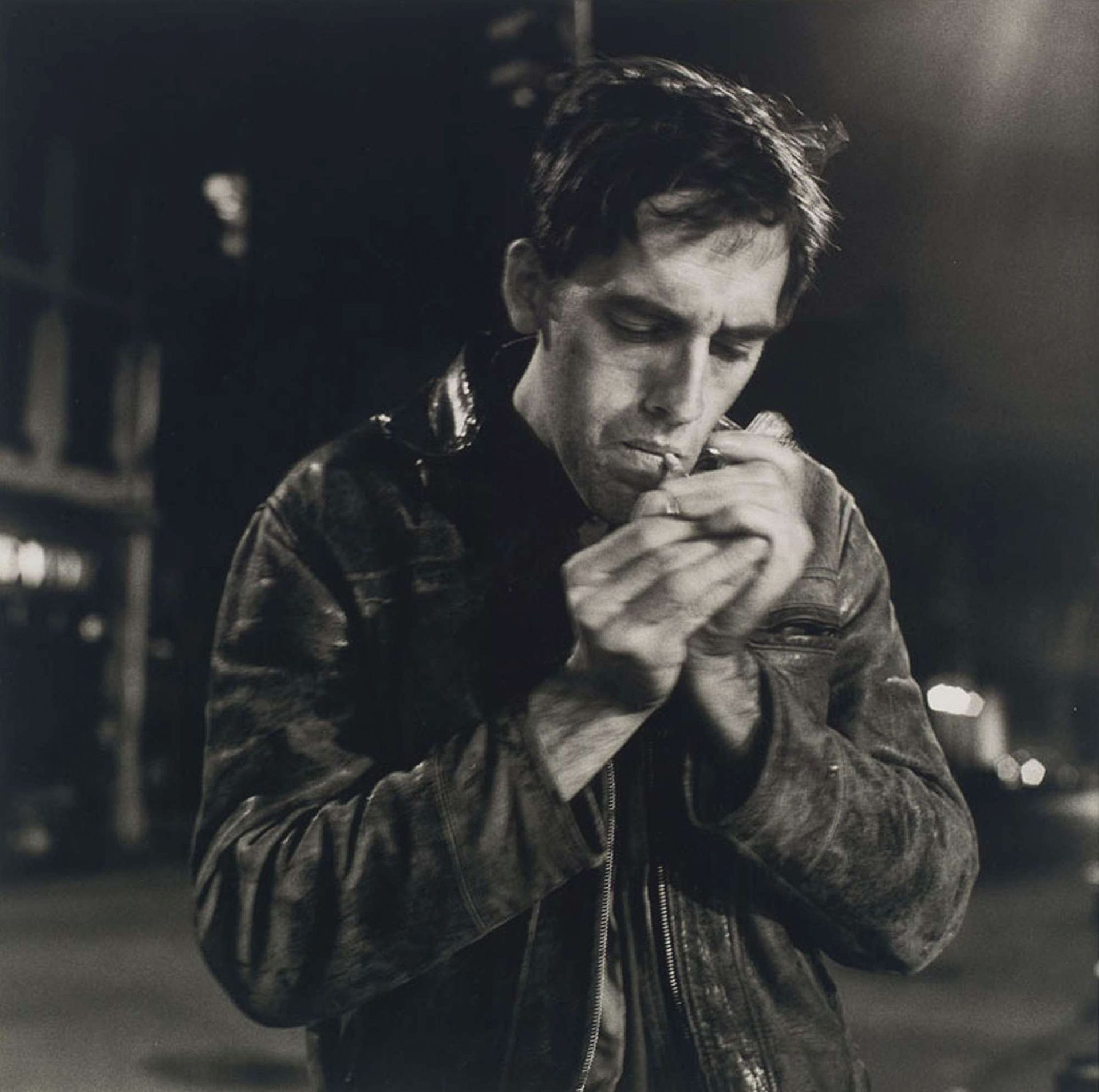

Ervell told the magazine Black Book that he chose the images for his campaign (in which not a shred of his own clothing is visible) because they are “deeply romantic”. He said he learned about Hujar’s work “from reading about the New York art scene from the early 1980s; he’s a contemporary of David Wojnarowicz, and even Mapplethorpe. He is the one who’s less known, a bit undiscovered. I feel like he’s ripe for rediscovery.”

Living to tell the tale If Ervell has been reading books on the period, he hasn’t been reading too closely: Hujar was 20 years older than Wojnarowicz and served as the younger artist’s most trusted mentor. But he is right about Hujar seeming to be of the moment. The Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco organised Love & Lust, an important exhibition of Hujar’s erotic portraits, last year, and Frish Brandt, the gallery’s president, says that more shows are planned, including a retrospective organised by New York’s Morgan Library & Museum, which is due to open in Spain in 2017 and in New York in 2018. Brandt believes that a certain amount of critical distance has helped to foster interest in Hujar specifically and the Aids crisis of the 1980s more generally. “The Aids crisis is not over, but we are hearing from a lot of people who lived to tell the tale,” she says.

In some cases, artists are driving the interest in friends who died from Aids. Take Tony Greene, whose sensuously layered, erotically themed paintings-on-photographs seemed to be out of step with the view of Aids-related work as politically oriented and were rarely shown after his death in 1990—until the Whitney and Hammer Museum biennials and the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in Los Angeles featured his work last year.

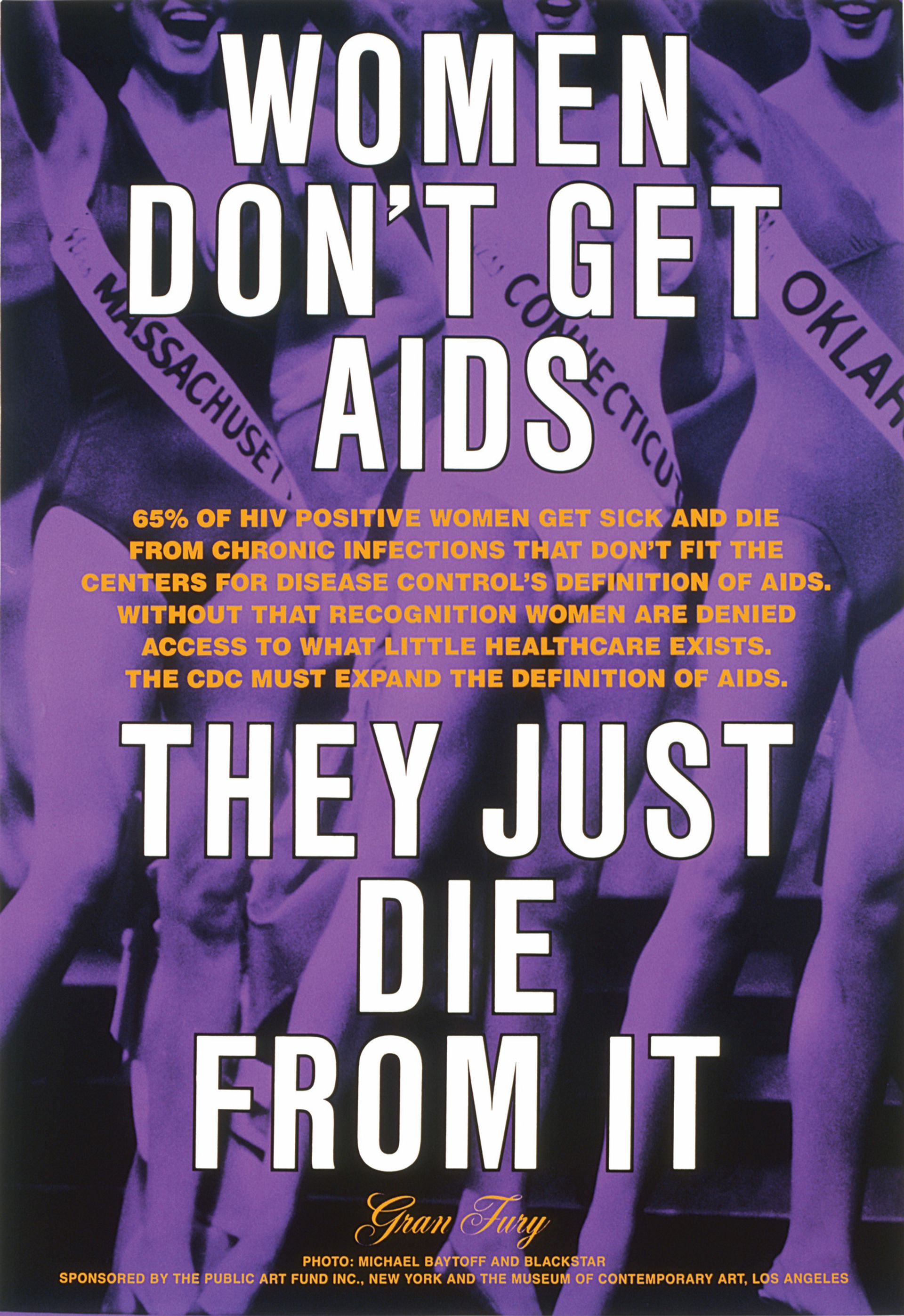

The artist Richard Hawkins, who organised the Whitney’s presentation with the photographer Catherine Opie, credits this interest partly to a younger generation of artists seeking “an alternative history to tie themselves to, one that could deal with taboos, desire, darkness and death in a way that Félix González-Torres and Gran Fury [an offshoot of Act Up] might not. Part of the issue has been that Félix and Gran Fury have come to stand in for the period and the unfairly generalised topic of gay/Aids/80s-90s/activism/proto-queer.” Hawkins calls Greene’s work “blisteringly sexy”.

Another artist whose work challenges the idea that Aids-related work hits only one or two notes is Danh Vo, who was not yet a teenager when the acronyms Aids and HIV were coined. He mined Martin Wong’s personal collection of oddities (hamburger ceramics, anyone?) for a show at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2013. This summer, he has co-organised a group exhibition for François Pinault’s Palazzo Grassi as part of the Venice Biennale. Slip of the Tongue (until 31 December) explores the idea of artists as caretakers of objects, using works by Wong, Hujar, Wojnarowicz and Paul Thek, among others.

Helen Molesworth, the chief curator at LA MoCA, who organised a show about Act Up when she was at Harvard University, points to historical curiosity, whetted by the campaign for gay marriage that has recently swept the US, as a motivation for museums to look back at this period. “We are surrounded by young people who don’t know what happened,” she said, noting that the show is being organised by Rebecca Matalon, a young curatorial assistant. “For people in their 20s and 30s, HIV seems like a chronic, manageable condition, like diabetes. In many ways, I’m extremely happy about that: I wish them nothing but safe sex. I think it’s important not to browbeat people about that, but to show them the extraordinary loss that gave them their freedom.”

David Breslin, who is co-organising the forthcoming Wojnarowicz retrospective with the Whitney’s curator David Kiehl, believes that nostalgia is playing a part. “It’s not just about the end of these lives, but the kind of art world that is no more,” he says. “This might be naïve, but I see a pre-professionalisation of art in this period. Artists could work with video, painting and performance and be writers, and not think ‘this is going to kill my market’. Collaborating with others was very fresh.”

Politics vs poetics As for the Wojnarowicz retrospective, Breslin says that the artist’s Aids activism is not the focus of the show. “We want to show his practice in all its complexity—writing, photography, collage, stencils, the pieces he did on [New York’s] piers, cartoonish graphic things like the huge cow heads that only exist through documentation by Peter Hujar,” he says. The exhibition will also include documentation of the artist’s role in the so-called culture wars. One video shows him fielding phone calls from reporters in 1989, after the National Endowment for the Arts withdrew its funding for a catalogue for a show at New York’s Artists Space because of Wojnarowicz’s controversial essay in it.

It is hard to predict how many museums will follow the dichotomy identified by the critic Douglas Crimp—a split between the elegiac, poetic expressions that “dominated the art world’s response to Aids” and more directly politically engaged works, which have a history of being marginalised. To what extent will these shows favour the former (say, González-Torres over Gran Fury) because they are more in keeping with “timeless” art-historical themes? How will the museums connect a single artist’s object-making and activism? And how many curators will figure out ways to transcend the basic art-versus-activism dichotomy?

The show at LA MoCA will separate “agitprop” from other works. The main exhibition space will host photographs by Goldin, sculptures by González-Torres and a Polaroid series (including flowers and drug trips) by John Boskovich, all drawn from the museum’s permanent collection. The entrance lobby will feature archival material from one of Gran Fury’s last public projects, sponsored by the museum and the Public Art Fund. It was a powerful bus-stop poster that read: “Women don’t get Aids. They just die from it.”

Catalyst for change Jonathan Katz, who co-organised Art Aids America, sees all the works in his show as political, even sculpture designed by González-Torres to pass as Minimalism. More broadly, he aims to show how Aids served as “the motor for significant changes in American art”, taking a wide view that includes around 120 artists. “One of our goals was to discover important artists who, by virtue of dying really, really young or living in geographically isolated places, never got the attention they deserved,” he says.

One discovery is a 1981 painting by Izhar Patkin, made after the Israeli-born artist first saw men suffering from the facial lesions then diagnosed only as Kaposi’s sarcoma. The abstract composition, titled Unveiling of a Modern Chastity, transforms the lesions into reddish blotches disfiguring the surface of the canvas, which is painted a putrid yellow. It is the earliest work in the show and, Katz says, the first work made about Aids.

“Getting an Aids show off the ground has been the most difficult experience of my life”

Katz, who co-organised the controversial exhibition Hide/Seek at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC (2010-11)—the museum removed Wojnarowicz’s video of ants swarming over a crucifix after pressure from Christian groups—has observed the growth of interest in Aids-related art as “museums are being critiqued for the erasure of queer history”. He says the Whitney’s presentation is a step in the right direction, but insufficient.

“It’s emblematic that we’re now seeing an Aids wall or an Aids segment, but getting a forthright Aids exhibition off the ground has been the most difficult experience of my life—much more difficult than Hide/Seek,” he says. “We [offered] Art Aids America to all the major museums, like the New Museum [in New York]. But the New Museum is not the New Museum of old, and the 1993 show [last year’s NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star] was its response.” He adds that his exhibition is not travelling to Manhattan or San Francisco, “though God knows we tried”.

Katz blames the conservative nature of museum boards, and the directors who report to them, for holding institutions back. “We think that museums, because they are formally adventurous, are at the leading edge of culture, but that formal ethos allows them to be culturally retrograde,” he says.

Where to see it: forthcoming US shows of Aids-related art 2015: Tongues Untied, 6 June-13 September, Pacific Design Center, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Art Aids America, 3 October-10 January, Tacoma Art Museum, Washington 2016: Art Aids America, 9 February-21 May, Zuckerman Museum of Art, Georgia; Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective, 15 March-31 July, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and J. Paul Getty Museum; Art Aids America, 23 June-11 September, Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York; David Wojnarowicz retrospective, Autumn (dates TBC), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York