Few visitors browsing the more than 150 stands at the Masterpiece London fair (25 June-1 July) realise how painstakingly the objects have been checked over. Whether it is a gold snuffbox, an Egyptian bronze statuette, an Andy Warhol portrait, a Jaeger-LeCoultre pocket watch, or a Sèvres soft-paste dish, everything has been vetted by specialists, of which there are more than 150, split into 28 committees. Vetting happens on a single day, with exhibitors absent until 1pm (unless they are vetters of other stands).

“We require that everything is a genuine work of art, of the period it’s supposed to be, in its original form,” explains Philip Hewat-Jaboor, who has chaired Masterpiece since 2012 and its vetting since 2010 (the inaugural year). The object must also be “fairworthy”, meaning “the very best of its type”.

At 8.30am on a Monday, the vetters gather for coffee and croissants. “The room is absolutely pullulating with scholars,” enthuses one vetter, the former director of the Scottish National Galleries, Timothy Clifford. “Many of the most learned people involved in that art form.” The committees—each with a chair and one or two scribes—then fan out across the fair. When a stand passes muster, they tick its checklist and move on. If there is a question mark—an object is actually from 1590, not 1580, for instance, or a table is English and 18th-century rather than French and 19th-century—a note is left for the exhibitor, and the issue gets resolved “nine-and-a-half times out of ten”, Hewat-Jaboor maintains.

Still, feelings do get hurt. One vetter recalls a clock dealer displaying a huge contemporary picture on his stand, painted by his daughter, whom no one on the relevant committee had heard of. Convincing the clock dealer to take the painting down proved fiendishly difficult.

When a disagreement of substance arises, the exhibitor can turn to the appeals committee, which convenes early on Tuesday and consists of Hewat-Jaboor and four other members, not all scholars (there is one QC, for example). The panel rules “based on the evidence, not on our own feelings”, says Hewat-Jaboor, and disputes “get resolved in large part wisely and amicably”. What about when sparks fly? “It’s obviously very disappointing and awkward,” replies Hewat-Jaboor with characteristic understatement. “I hope on the very small number of cases it happens that one manages to be understanding and diplomatic.”

Hewat-Jaboor says vetting committees have fewer exhibitors nowadays, as he is “working very hard” to achieve greater balance by mixing in scholars, academics and conservators. At the same time, it makes sense to include exhibitors, he says, simply because they are on hand to vet objects that are added in mid-fair.

When an object is particularly large, rare or challenging—an unwieldy wall mirror, for instance, or a very recherché piece—Masterpiece suggests that it be pre-vetted in advance of the fair to avoid difficulties such as having to move an item on the day or requiring more time to examine it properly.

Diligence, fairness, and diplomacy seem to be Hewat-Jaboor’s guiding principles. “It’s really important for people to know the rigour we apply to every single work of art that is exhibited there, whether it’s a £500 thing or a £5m thing,” he says.

Passed muster: items from this year’s Masterpiece that gained the vetters’ stamp of approval

Errol Manners, European ceramics

Errol Manners got an early start, handling porcelain as a 24-year-old porter at Christie’s. For eight hours a day, wearing a green overall, he handled hundreds of objects in the ceramics warehouse. Before a sale, his job was “to stick the right label on the right object”. Manners then transferred to the Chinese department and, after an 18-month stint on Portobello Road, started dealing on Kensington Church Street, where he is still based.

As chair of Masterpiece’s European ceramics vetting committee, he makes sure time is well spent on vetting day—“we sometimes find we’re arguing about one teapot for one hour”—and arbitrates when disagreements come up. Objects that “flash up red light signals” are pieces of Sèvres porcelain that were sold blank around 1800 and had decoration added on a few decades later. “We would refuse an item like this, generally, as a fake, although it might be 160 years old,” he explains. Other unacceptable items are ones that are “over-restored or a poor example or in any way misleading”.

The “Vetting off” (the process of rejection) of works “is usually pretty amicable: they just put it away”. Occasionally, however, there can be pride and money involved, “sometimes a great deal of money, and that’s a recipe for an unhappy situation”.

Technology can help to date a work. A handheld X-ray fluorescence machine detects chrome in the green enamel—a material that cannot have been used in enamel on porcelain before 1803. But ultimately, says Manners, “vetting is 95% connoisseurship and 5% science”.

Floris van der Ven, Chinese ceramics, furniture and works of art

Floris van der Ven caught the antiques bug 28 years ago when he worked for a summer in his aunt and uncle’s Oriental art gallery. Now a specialist in Chinese art (his gallery in ’s-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands sells porcelain, early terracotta from the Han and Tang dynasties and other works), he is a vetter at The European Fine Art Fair (Tefaf) and Masterpiece, where he chairs the Chinese ceramics, furniture and works of art committee for the first time this year, as well as having a stand. He denies any conflict of interest. Twenty-five years ago, there was “a lot of politics going on in vetting: people had an interest financially in items, or didn’t like the dealer”, he says. Today “there are so many firewalls built in” to prevent foul play.

When it comes to Chinese porcelain, he has his eyes peeled for 19th-century copies, but also modern ones purporting to be centuries older, which pop up at small auctions or bric-a-brac shops in the West. The fakers “are good at it, but we can still beat them”, says Van der Ven, who makes regular fact-finding trips to the Chinese porcelain capital Jingdezhen (in Canton) where fakes are made.

He can usually spot a fake almost instantly, because “they don’t get the shapes right, or the right kind of blue, or the right kind of yellow”.

David Ellis-Jones, 20th-century paintings, watercolours, drawings and sculpture Modern pictures specialist David-Ellis Jones has two decades of vetting under his belt—mostly at Grosvenor House, the forerunner of Masterpiece London (which ended in 2009). As a young man, he gave up plans to become a doctor and got a job at Sotheby’s, then worked for many years at Wildenstein & Co. Now chair of Masterpiece’s 20th-century paintings, watercolours, drawings and sculpture committee, he is fixated on one thing: authenticity.

Whenever “there are catalogue raisonné references missing, (the work should have a certificate but doesn’t, or the documentation is not enough)”, a perfectly genuine work can be kept off a stand. And with the art of the last couple of centuries, attribution cannot be vague. “You can have a gold-ground picture attributed to Duccio that’s perfectly acceptable,” he explains. “But you can’t have ‘attributed to Hockney’.”

In his years as a vetter, Ellis-Jones has experienced some odd episodes. At Grosvenor House, he remembers a dealer bringing a “rather nice” Augustus John drawing and cataloguing it as a self-portrait of the artist. (Self-portraits are worth more than portraits of an unknown sitter.) When vetters objected that John looked nothing like that and that the piece should be relabelled a portrait, “the dealer was absolutely furious and took it off the wall.” Yet for the next two years, he kept bringing the same drawing back. “He thought he might get away with it,” Ellis-Jones says.

Arie Hartog, Sculpture and works of art 1830-1930

As the director of the Gerhard Marcks Haus museum in Bremen, Germany, which he joined as a curator in 1996, Arie Hartog—chair of Masterpiece’s sculpture and works of art 1830-1930 vetting committee—has a passion for German and French sculpture. He also loves vetting; after his very first day of it four or five years ago, he told colleagues back at the office that he’d learned more in one day than at three years of university.

As a sculpture vetter, Hartog looks out for posthumous bronze casts that are passed off as lifetime works, or as casts much older than they actually are. Hartog and his team rely on their eyes and noses to weed out anomalies. By looking at a bronze, for instance, Hartog can tell if it is recent, because it will bear traces of a machine used on bronze after 1980. And a French fellow vetter can more or less date a bronze by sniffing it. “The younger the bronze, the more traces of acidity, which you can detect by smell or taste. But nobody is going to lick a bronze,” Hartog says.

One problem subject is Aristide Maillol. The market is flooded with posthumous pieces made from elements found in his studio —it was something the copyright owner had the right to do. The label on one of those “shouldn’t say it was conceived early and cast early”, Hartog says. Why? A lifetime Maillol can cost as much as 20 times more than a posthumous one.

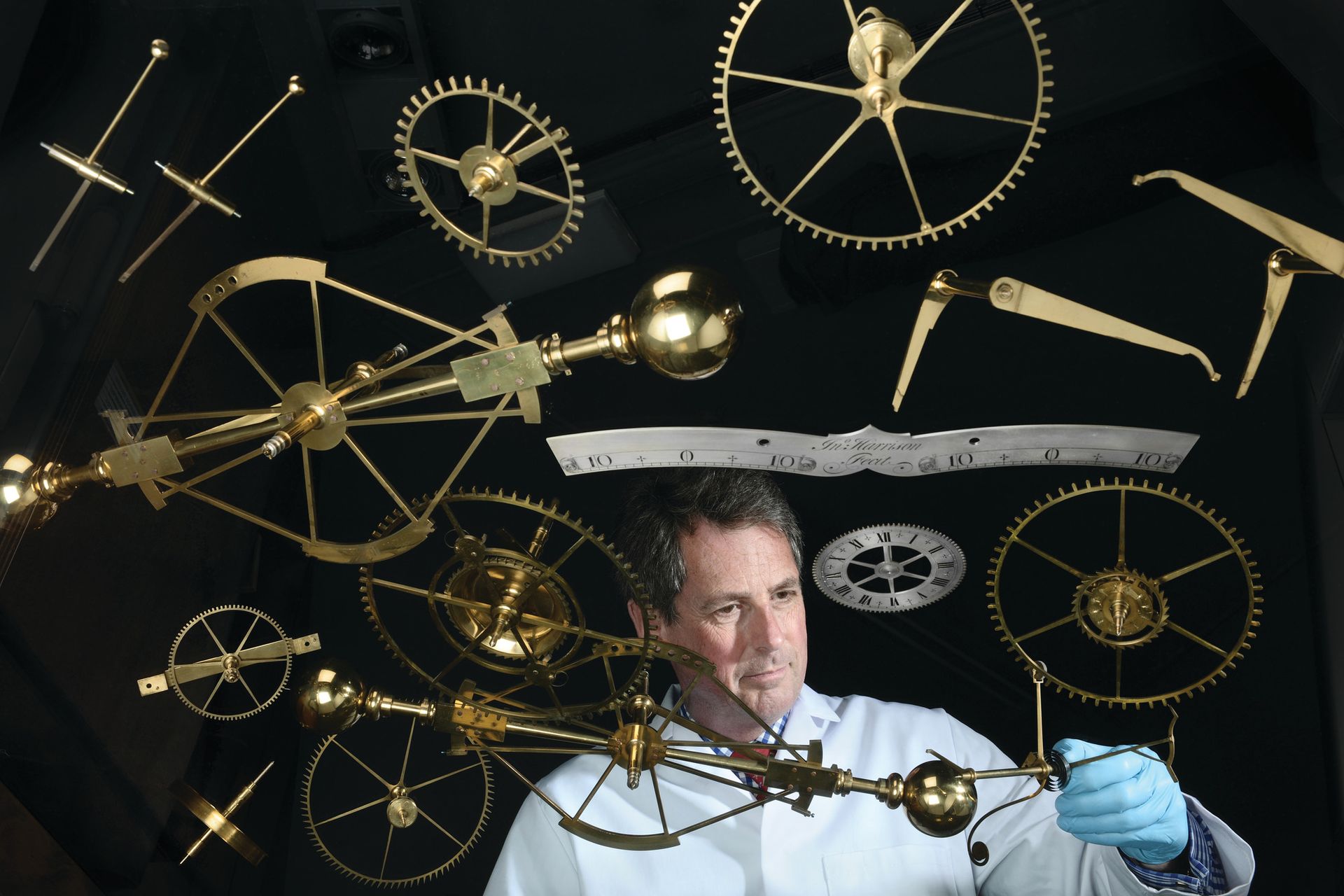

Jonathan Betts, Clocks

Keeping time is a family affair for Jonathan Betts. The clocks specialist is the son and grandson of watchmakers and jewellers, and spent childhood holidays as a runner between the shop and the workshop, where he gazed in awe at the men behind the benches repairing watches and clocks. Though his father feared that quartz technology would extinguish the profession, Betts studied technical horology and joined the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich in 1979, where he spent 35 years as a restorer-curator until his recent retirement.

For Betts, vetting involves “getting inside a case with a torch and looking down into the carcass: you really have to get on your hands and knees sometimes”. He can’t remember a fair where everything got “a bill of health”. Antique clocks are usually several hundred years old, and at that age, there are replacements, which is fine—as long as it says so on the label.

“Alarm bells start to ring” when a clock has been made of the components of several different clocks, he says. Also, restorers make something look older than it is. Yet they “give the game away by just slightly overdoing it”: exaggerating the rust on a wooden clock case’s new hinges, or using chemicals to make an object look old. Whenever such issues crop up, Betts and his team raise their objections amicably and diplomatically. “There are no punch-ups,” he says.

Lindsey Stewart, Photography

In two decades running the Christie’s photography department, Lindsey Stewart viewed many outstanding prints before they hit the saleroom. Now a consultant specialist in photographs at Bernard Quaritch in London, which she joined in 2005, she chairs the photography vetting committee at Masterpiece. She also vets at Tefaf and the Fine Art & Antiques Fair at Olympia.

In a typical year at Masterpiece, visitors might expect to find works by Josef Koudelka, Henri Cartier-Bresson or William Klein. Stewart makes sure that every print at the fair is signed or stamped by the photographer, and if not, unequivocally attributable to the photographer or his/her studio. She also ensures that a distinction is clearly made between vintage prints and much later prints, as “there can be a big price difference”, she says. She and her team sometimes use ultra-violet lights as a dating tool, as from the mid-1950s onwards, bleaches were introduced in photographic paper and can be detected.

To go on show at Masterpiece, a photographer must be well known. “Most people don’t have friends who make pieces of furniture or ceramics or glass, but they might have friends who are very good photographers,” she explains. When that friend does not “have a reputation already”, the photograph gets vetted off the stand.

Fakes are not much of an issue. “For many years, it simply wasn’t worth the effort… the value of photographs was relatively low until fairly recently,” Stewart says.

Joanna van der Lande, Antiquities

Joanna van der Lande is not sure how she caught the antiquities bug, but wonders if it was the childhood holidays that she spent with her brother digging up a German aeroplane that crashed in 1940 in a field behind their Surrey house. Van der Lande went on to run the antiquities department at Bonhams for 17 years and is now a consultant—and chairs the Antiquities vetting committee at Masterpiece.

She checks ownership, history and provenance and sometimes asks not just for paper evidence but also for the results of a thermoluminescence test and carbon dating. Only one or two items get vetted off every year, on average.

Her team is particularly sensitive to items from the Middle East. “Iraq and Syria are top of the list… we’re all rather conscious of the difficulties” and the risk of illicitly removed objects, she says, though she has yet to see any such object in London.

The vetters use low-tech tools such as a magnifying glass, an LED torch and sometimes their nose. “If there’s an unglazed pottery object and you’re worried about it, if you dampen it, it should emit a musky smell,” she explains. “If it’s odourless, it means it might not be ancient.”

Patrick Elliott, Sculpture and works of art 1830-1930

Patrick Elliott, chief curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art since 1989, is a seasoned vetter at both Masterpiece and Tefaf (although he will miss Masterpiece this year as he is opening a museum show that week). “Six experts from Britain, France and Germany all chatting about the underside of a Rodin: it’s an absolute treat,” he says.

Key concerns are “when the thing was cast, was it cast legitimately? And making sure it complies with the rules of posthumous casts.” On that last point, “there’s a lot of smoke and mirrors”, he says, because all Degas sculptures and almost all Gaudier-Brzeska and Duchamp-Villon ones are posthumous, and in the case of Rodin, they are still being produced.

The question becomes how posthumous a cast is. At Masterpiece, a sculpture has to have been cast fewer than 25 years after the death of the artist, or with wholly posthumous editions, the edition has to have been begun fewer than 25 years after the artist’s death. In both instances, the casting has to have been initiated by direct descendants or copyright holders.

“If someone was to shell out £1m on a bronze and find out it was cast 50 years after the artist’s death, it might prick their ears up,” he says.