“High-priced art is this month’s face of the world’s growing concentration of super wealth,” proclaimed the NPR radio host Tom Ashbrook last month, following a fortnight of auctions in New York in which price records were pulverised. In total, almost $2.5bn was spent across six evening auctions of Impressionist, Modern and contemporary art.

Brand names were key, as buyers sought trophy works. A senior Christie’s employee told The Art Newspaper that a certain class of buyer only wants to engage in works estimated to sell for more than $100m. At this level, the spending is less about the quality of the work than a demonstration of one’s wealth.

The auction houses are chasing the masses of money held by the 0.01%, both established buyers from the US and Europe as well as new players from regions including Asia, the Middle East and elsewh ere. In their attempts to grab market share, the houses are being liberal with their business-getting methods. Christie’s use of guarantees and other—somewhat unclear—financial arrangements reached almost absurd levels this season: 51% of the lots in its 11 May auction and 61% of its 13 May auction were guaranteed, either by the house, third parties or a mixture of both, or were subject to some other kind of financial pre-arrangement. “A guarantee should be considered a pre-sale—which in fact it is,” says the dealer Edward Tyler Nahem, founder of the eponymous gallery.

Sense of distortion

These kinds of financial arrangements help risk-averse sellers commit works to auction, and guarantees do not necessarily “stop you outbidding that guarantee if you want”, says Hugh Gibson, a director of Thomas Gibson Fine Art. But these measures add opacity to the market and create a sense of distortion.

Christie’s $1.6bn bonanza began on 11 May with a standalone sale, Looking Forward to the Past, totalling $705.9m for 34 works created between 1902 and 2011. This included the sale of Picasso’s 1955 painting, Femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’), for $179.4m—the most expensive work ever to sell at auction. The painting previously belonged to the New York collectors Victor and Sally Ganz, and had sold for $31.9m at Christie’s in 1997.

Last month, it carried the highest ever pre-sale estimate for a work—$140m—and there was no doubt that it would sell since Christie’s had guaranteed it (and made financial arrangements with a third party to underwrite some of its risk).

The records kept tumbling at Christie’s postwar and contemporary art sale on 13 May, which made $658.5m in an 82-lot sale. New price levels were set for artists including the late Lucian Freud, whose Benefits Supervisor Resting (1994) sold to the dealer Pilar Ordovas for $56.2m (est $30m-$50m). The house had guaranteed the painting. “I’d call that an ample price,” said David Nash, the co-founder of Mitchell-Innes and Nash gallery.

Another work from the four-painting series, Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995), had briefly been the most expensive work by a living artist when the collector Roman Abramovich bought it for $33.6m in 2008. (The record now belongs to Jeff Koons, whose Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994-2000), sold for $58.4m in 2013.)

Finally, Christie’s Impressionist and Modern sale on 14 May totalled $202.6m, with Piet Mondrian’s beautiful Composition No. III with Red, Blue, Yellow and Black (1929) selling to the adviser (and Christie’s former chairman of post-war and contemporary development) Amy Cappellazzo for $50.6m (est $15m-$25m).

Sotheby’s in second place

Meanwhile, Sotheby’s had kicked off the season with a $368.3m auction of Impressionist and Modern art on 5 May—the second highest total in the company’s history for this sector. The top lot, Van Gogh’s L’Allée des Alyscamps (1888), was bought by an Asian client in the room for $66.3m (est in excess of $40m).

Set in a Roman burial ground in Arles, Van Gogh was working side-by-side with Paul Gauguin on this painting, before the artists fell out and Van Gogh suffered his legendary breakdown. Some dealers criticised the work, which had previously been sold by a Japanese collector in 2003 for $11.8m ($12m-$18m). “It’s a bit flat and the subject matter is a little banal to my mind; it’s not Van Gogh at his most innovative,” said Andrew Fabricant, a partner at Richard Gray gallery. “But when you get a painting by an artist of that size, people don’t look critically. The name carries so much weight.”

Sotheby’s contemporary sale on 12 May totalled $379.7m. The top lot was a 1954 yellow-and-blue abstract by Mark Rothko, which sold for $46.5m (est $40m-$60m). The work had once belonged to the US collectors Paul and Bunny Mellon—and more recently to the owner of rival firm Christie’s, François Pinault, who had sold it in 2013.

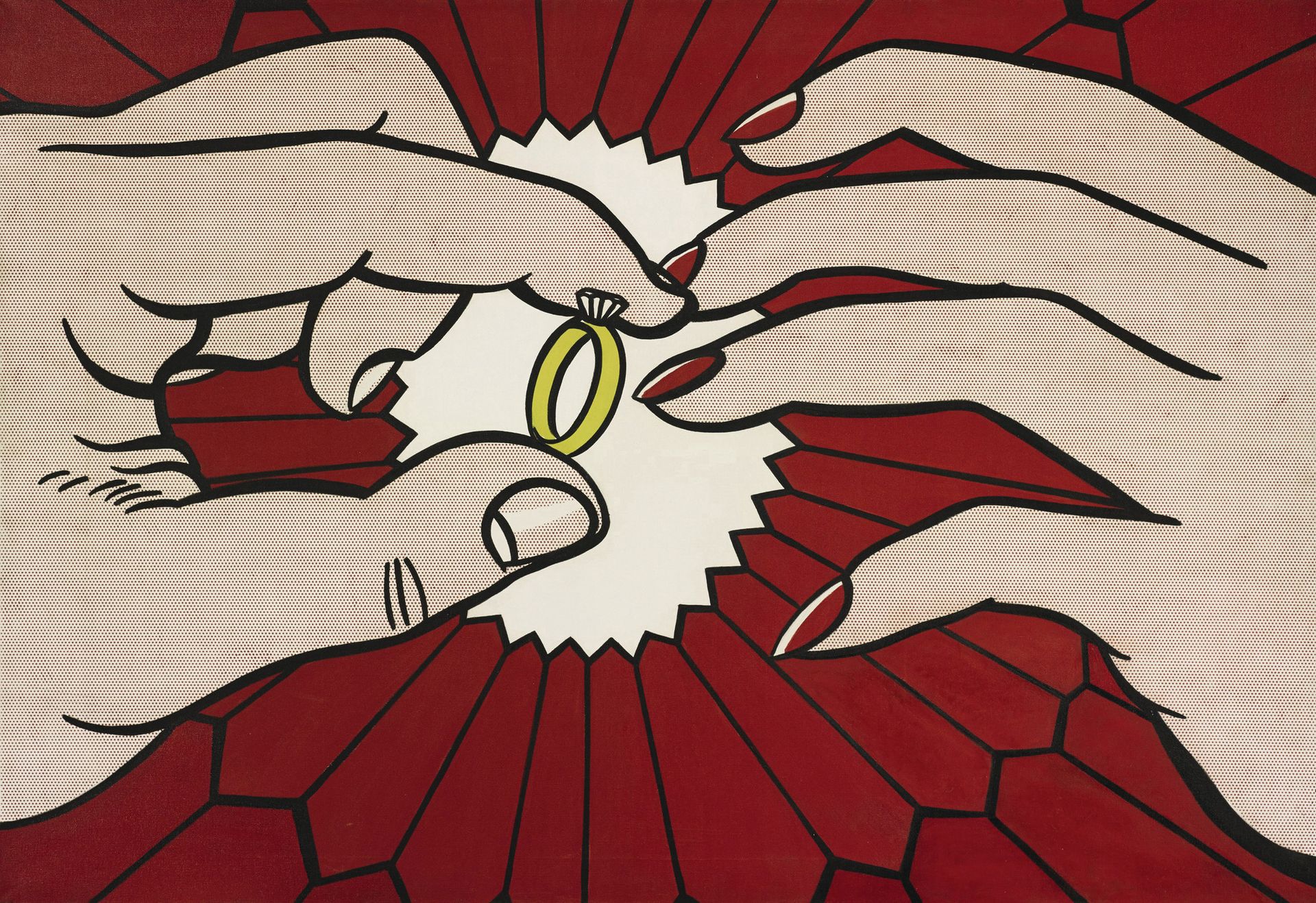

The flipside of guarantees was apparent in Sotheby’s sale of Roy Lichtenstein’s 1962 painting, The Ring (Engagement). Sotheby’s had guaranteed its seller, the Chicago collector Stefan Edlis, a certain amount. But, it fell short of its $50m pre-sale estimate, hammering at $37m ($41.7m with fees), which means someone, somewh ere (likely Sotheby’s) took a hit. There was a similar lack of excitement for Phillips’s top lot on 14 May; Francis Bacon’s Seated Woman (1961) was guaranteed by a third party but hammered at its low pre-sale estimate of $25m ($28.2m with fees).

There were several such moments that suggested turbulence in the otherwise bullish market. Another head-scratcher was the sale of Giacometti’s L’Homme au Doigt (1947) at Christie’s on 11 May. Estimated in excess of $130m, the work set a new record for the artist at $141.3m—despite only receiving one bid (Marc Porter, Christie’s chairman of the Americas, on the phones). And while there was a new record set for Christopher Wool with Sotheby’s sale of Untitled (Riot) (1990) on 12 May for $29.9m (est $12m-$18m), there was no buyer the following evening at Christie’s for another 1990 painting of his, Hypocrite (est $15m-$20m).

Such disappointments amid such wild excess made some dealers unsure about how sustainable the current state of affairs really is. “It’s an unreal world; we had a great opening at Frieze New York, and now these auctions,” says the European dealer Thaddaeus Ropac, founder of the eponymous gallery. “You need to be careful not to get used to it.”

With additional research by Richelle Simon

Auction results, New York, 5-14 May

Sotheby’s, Impressionist and Modern art, 5 May

Sale total: $368.3m (est $257.6m-$351m)

Lots offered: 64

Sold by lot: 78.1%

Christie’s, Looking Forward to the Past, 11 May

Sale total: $705.9m

(est $577.7m-$667.5m)

Lots offered: 35

Sold by lot: 97%

Sotheby’s, contemporary art, 12 May

Sale total: $379.7m (est $315.1m-$411.2m)

Lots offered: 63

Sold by lot: 87.3%

Christie’s, post-war and contemporary art, 13 May

Sale total: $658.5m

(est $494.6m-$687.5m)

Lots offered: 82

Sold by lot: 88%

Christie’s, Impressionist and Modern art, 14 May

Sale total: $202.6m

(est $106.5m-$159.6m)

Lots offered: 43

Sold by lot: 93%

Phillips, contemporary art, 14 May

Sale total: $97.2m (est $96.1m-$138.3m)

Lots offered: 70

Sold by lot: 80%

Please note: Results include buyers’ premium; estimates do not. In London, Sotheby’s buyers’ premium rates are 25% on the first £100,000 ($200,000 in New York); 20% between £100,000 and £1.8m ($200,000 and $3m) and 12% above this. Christie’s and Phillips’s rates are 25% on the first £50,000 ($100,000); 20% between £50,000 and £1m ($100,000 and $2m) and 12% above this.