Panel 60, the final painting in Jacob Lawrence’s epic Migration Series (1941), depicts a growing crowd of black men, women and children huddled closely together on a train platform. Clusters of luggage sit at their feet as they face the railroad tracks, hopeful their journey will lead to a new life. The anonymous figures (no faces are depicted) are all painted in Lawrence’s signature reduced palette of ochre, mustard yellow, forest green, cornflower blue, rich brown and black. A caption penned by Lawrence accompanies the painting and reads: “And the migrants kept coming.”

This open-ended conclusion reinforces the narrative of the Migration Series, a suite of 60 paintings illustrating the mass exodus of African-Americans from the American South to Northern cities such as New York, Chicago and Detroit at the dawn of the First World War and lasted until around 1970. It is one of the artist’s greatest triumphs and for the first time in 20 years, the full suite is currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in the exhibition One Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Works.

Born in 1917 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Lawrence spent his childhood in rural Pennsylvania and Philadelphia. His mother settled her family in Harlem during Lawrence’s early teenage years and in 1941, he married fellow Harlemite and artist Gwendolyn Knight. Although both of his parents were Southern and were among the first wave of migrants to move North, Lawrence did not visit the South until after he completed the Migration Series. “The Great Migration is a part of my life,” Lawrence wrote in a 1992 exhibition catalogue. “I grew up knowing about people on the move from the time I could understand what words meant.”

Lawrence began his research for the series in 1940 at the age of 23, soon after he completed pictorial accounts of the revered abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. The Migration Series would become the fourth historical suite created by the artist over a span of only four years that started with The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture (1938). Similarly to the way he approached previous projects, Lawrence spent long hours at the 135th Street library in Harlem (now the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture) studying ephemera, books, journals, and periodicals for inspiration. But unlike his other historical works, the Migration Series chronicled an extraordinary socio-political movement that was primarily leaderless, rather than focusing on the intrepid actions of an exceptional leader. Upon the completion of the Migration Series, MoMA agreed to purchase the even numbered panels and Duncan Phillips acquired the paintings with odd numbers in a unique arrangement.

The 60 works, rendered in tempera paint applied directly to board, vary in content and composition. Panels depicting the migrants’ journeys are interwoven with pastoral and architectural abstractions. However, it is Lawrence’s paintings of domestic spaces that resonate with the greatest emotion. Moving portrayals of families or individuals hunched over dinner tables in sparse tableaus evoke the psychological toll of Southern life. Although the North promised a better future, Lawrence captured the challenges migrants faced in their new cities, such as housing shortages and crowded living conditions. For example, panel 47 shows nine figures sleeping huddled together under colorful blankets in a bare tenement.

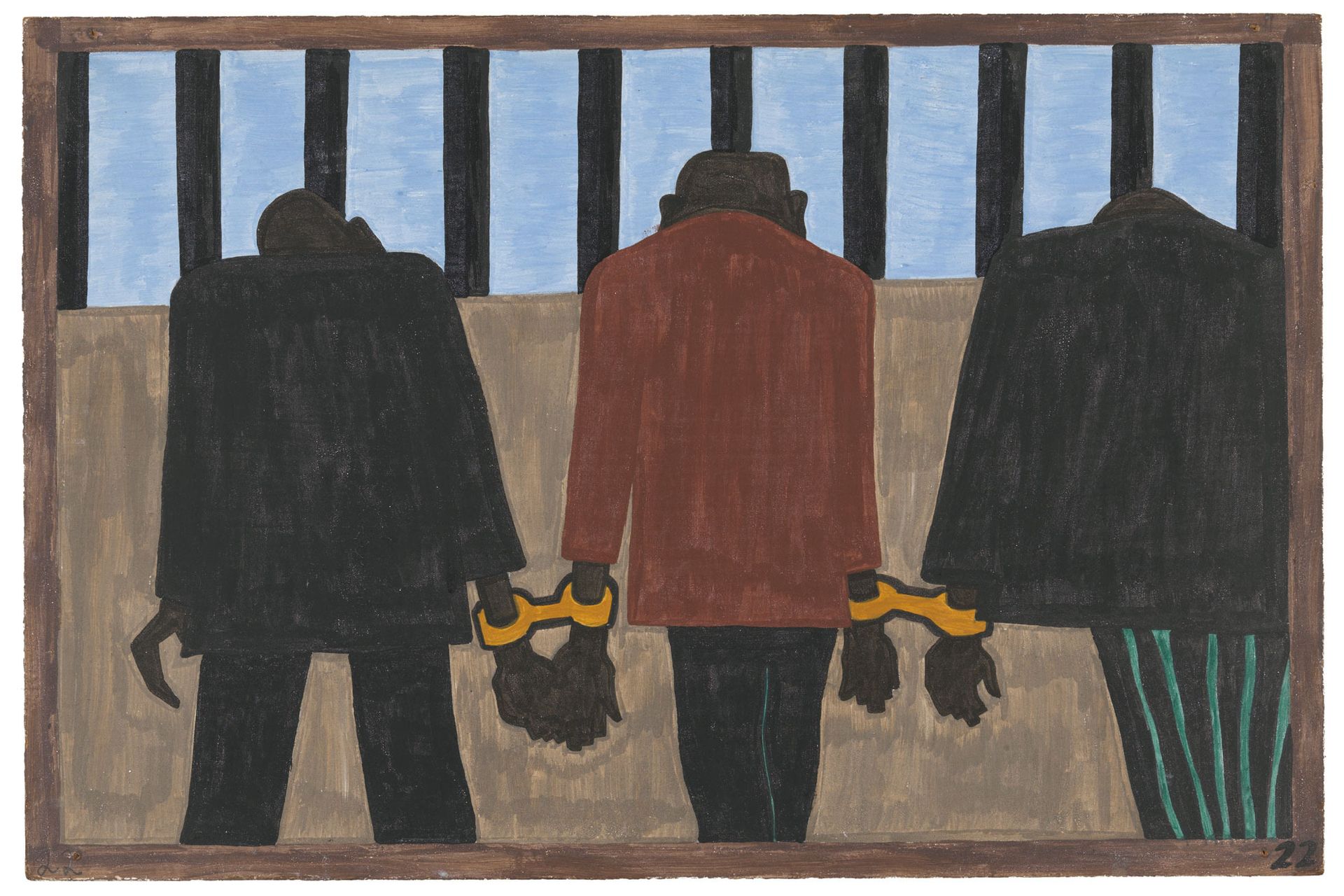

Several of Lawrence’s panels resonate eerily with current events, as tensions continue to build across the US over the killing of black men by police. In a caption that could easily have been written today, panel 22 reads: “Migrants left. They did not feel safe. It was not wise to be found on the streets late at night. They were arrested on the slightest provocation.” The accompanying image depicts three men handcuffed together. Their vertical stances echo the barriers of the jail cell.

The title of the exhibition, One-Way Ticket, refers to Langston Hughes’s 1949 poem of the same name in which he expresses frustration over Jim Crow laws and describes a determination to find a home anywhere but the South. The poem sets the tone for this comprehensive show that includes not only Lawrence’s Migration Series, but also comparative works by his friends and colleagues active in the Harlem arts community. Figurative paintings by Lawrence’s mentor Charles Alston as well as canvases painted by Romare Bearden and William Johnson hang in a gallery adjacent to the Migration Series. A display of groundbreaking novels and poems authored by Alain LeRoy Locke, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, James Weldon Johnson, and Richard Wright further emphasise the influence of the Great Migration on American literature. Aaron Douglas’s signature silhouetted figures grace the covers of many of these publications.

A separate gallery is devoted to photographs by Ben Shahn, Aaron Siskind, Gordon Parks, Dorothea Lange and others. Their photography captures raw, everyday moments ranging from quiet contemplation to celebration. Pictures of Southern farm workers and cotton fields contrast with images of Harlem’s bustling streets and emergent political activism.

Music weaves the show together with galleries dedicated to the leading blues and jazz artists of the 1920s and 1930s. The powerful vocals of Bessie Smith and Mahalia Jackson as well as the iconic sounds of Duke Ellington, Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong add a moving sonic element to the exhibition. Most captivating are the 1939 performances of Billie Holliday singing Strange Fruit and Marian Anderson’s Easter Sunday concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Their voices resound with courage and send shivers down the spine.

Organised at MoMA by the curators Leah Dickerman and Jodi Roberts, One Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Works is a smart and thoughtful show. The catalogue includes in-depth essays on the Great Migration and the evolution of Lawrence’s Migration Series. MoMA’s excellent auxiliary exhibition website features extensive historical and cultural content related to each panel of Lawrence’s suite. Biographies of key people included in the show, as well as a section featuring commentary about the Harlem Renaissance from contemporary artists and scholars, provide additional information about this landmark period of history. This poignant exhibition is not to be missed.

One Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Works, Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 7 September

Joanna Robotham is an assistant curator at the Jewish Museum in New York.