There is beauty in violence. If there is one lesson to draw from All the World’s Futures, the curator Okwui Enwezor’s main exhibition at the Venice Biennale, it is that great art can brutalise the imagination; that it can inspire aesthetic terror, the kind that is only felt and ultimately impossible to explain. Violence in the art of Christian Boltanski, John Akomfrah, Andreas Gursky, Chantal Akerman, Steve McQueen and Adrian Piper—whose pieces are among the best in the entire exhibition—is not open to exegesis; it cannot be made sense of. It can only be experienced for what it is: beautiful in its searing brutality.

Yet critics have been remiss. Instead of letting gorgeous savagery overwhelm their senses, they have either resisted it or have tried to explain it away. In ArtNews, Andrew Russeth wrote that the strife-filled show was “thankfully… punctuated by moments of quiet, resilient beauty”, as if there were no allure to the best and most vicious piece in the show, Christian Boltanski’s film L'Homme qui tousse (1969), in which a hooded man sits alone on the floor of a darkened room and vomits blood while convulsing, entirely absorbed in his vile illness. Beauty is nothing if it does not grab hold, and this haunting film refuses to let go.

In Vulture, the critic Karen Archey wondered why “there was little apparent joy… and [so] few moments of aesthetic respite” in the show, effectively disregarding the perverse pleasure of John Akomfrah’s fantastic film Vertigo Sea (2015), which pairs sweeping aerial views of oceans and the Arctic with sickening documentary footage of a harpooned whale gushing blood and a polar bear shot at close range by a hunter. Beauty hunted and killed is beautiful no less.

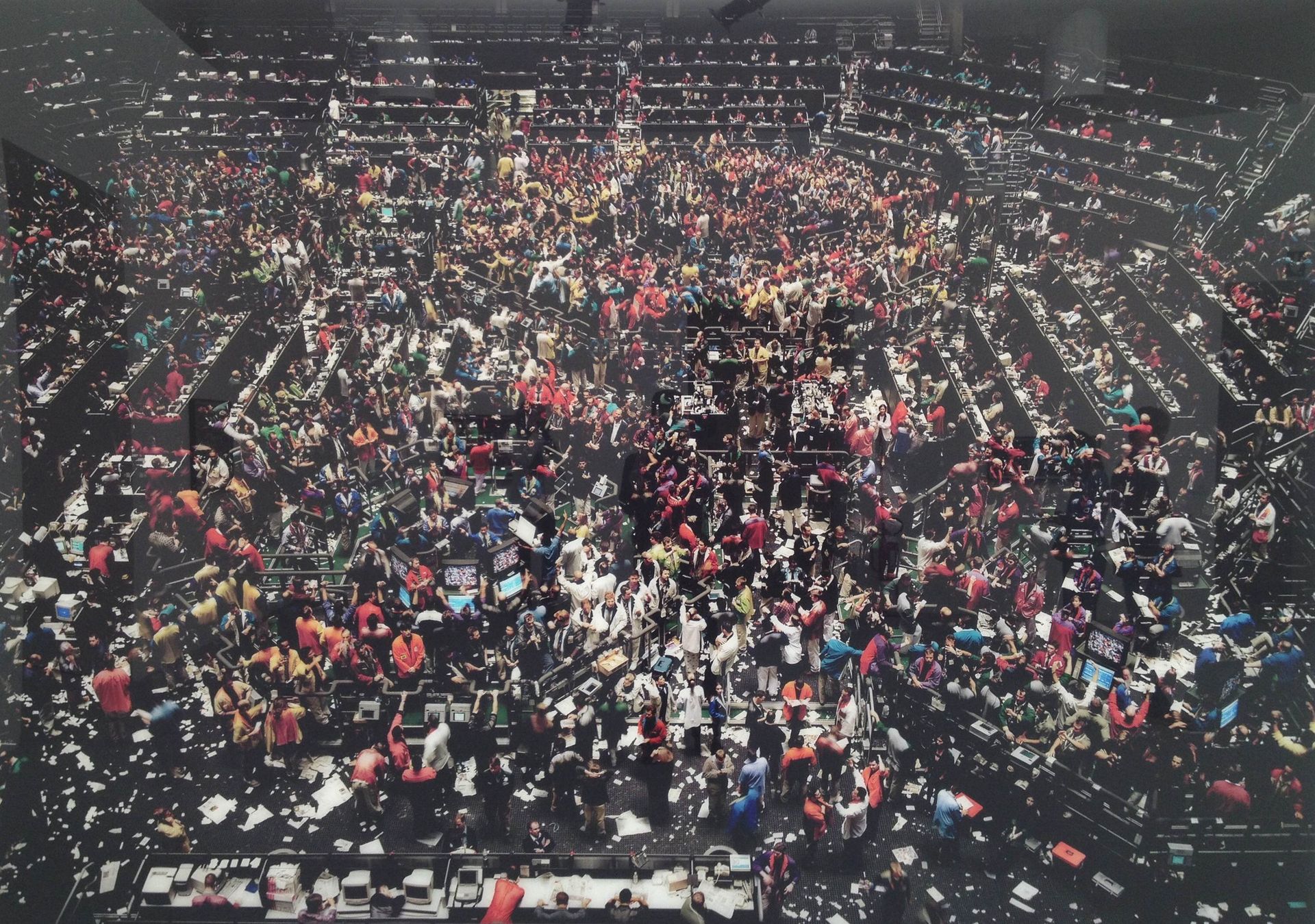

In the New York Times, Roberta Smith overstated her case when she wrote that the exhibition was “single-minded” in its insistence that “art is not doing its job unless it has loud and clear social concerns”. Where are the social concerns in Andreas Gursky’s gorgeous photograph Chicago Board of Trade III (1999/2009), where the violent, disordered scrum of a trading floor is rendered in detached simplicity? This picture is vacant of political commentary. It takes the capitalist world as it is and presents it beautifully, without any impulse towards critique. There is no need for Smith to interpret the show so deeply. The art says clearly everything it needs to say.

Critics have hemmed too closely to Enwezor’s curatorial line. They have strained too hard to see how an exhibition of 136 artists can be marshaled into a single theme. The result has been recourse to the most banal of points: that the exhibition is meandering and uneven. Of course it is meandering and uneven. There is a tremendous amount of terrible art on display and most of it has nothing to do with violence. (Terry Adkins’s stupid assemblages of unrelated objects—really, it is just stuff on top of stuff—are especially bad.) A show of this size necessarily outstrips a single idea. All the World’s Futures cannot come together perfectly, so it is ridiculous for Benjamin Gennochio to write in Artnet that “dogma rules in a show which is pretty well devoid of beauty, aspiration, irony or fun.”

The exhibition is too big for such sweeping gestures. Yet Enwezor’s task, as a curator, is to bind the hundreds of works on display in at least some fashion, so he insists on the turbulent capitalist context in which all the art was made. “Here we are,” he writes in the catalogue essay, “standing, puzzled, looking with scrutiny at the inscrutable; a plateau of debris stretching across the horizon.” We live in the unfolding aftermath of the furious birth of capitalism. Conflict, which “is always born of discontent,” is everywhere and “regardless of where in the world one lives, every waking hour is saturated with terrible news from elsewh ere: San’a, Aleppo, Mosul, Tripoli…” Enwezor’s list carries on.

The world has always been violent and confusing, but Enwezor is right to insist that capitalism has accelerated the pace and furor of coercion. These are not peaceful times. But neither are they explicable. It is appropriate that there are more questions than answers in the catalogue (“Does history always repeat itself? Where does art stand in this process of endless historical returns?”) because no one is clear-eyed in our day. Enwezor’s stated ambition to encapsulate “the state of things” is undercut by the state of things, which are unintelligible and unreasonable. Our existential anxiety is beyond comprehension. We can only feel our way through a violent world because violence itself is never reasonable; it is always the result of feeling.

Yet the most impoverished art in Venice makes dishonest conceptual claims on our brutal world, as if violence were merely an abstract idea and not a lived experience. In Isaac Julien’s video KAPITAL (2013), which depicts the artist in public conversation with the Marxist economist David Harvey, the two talk as if the tremors of capitalism can be rationalised and put into neat categories. This is the Marxist solution. But felt fear is an individual aesthetic experience. It has nothing to do with history, let alone historical materialism. Julien’s pedantic film, with its hectoring insistence that there are answers to Enwezor’s questions, has it all wrong.

Likewise, most of the work made from weapons (or made to resemble weapons) does not go far enough. Adel Abdessemed’s stacked swords (Nympheas, 2015), Pino Pascali’s artillery gun (Cannone semovente, 1965) and Monica Bonvicini’s hanging chainsaws (Latent Combustion #1, 2015) are all handsome pieces, but they are inoffensive. They only suggest violence instead of bathing us in it. It is impossible to be afraid of these modestly-sized sculptures. Even otherwise strong work by a good artist like Melvin Edwards does not do enough in this context. Although his finely-fashioned abstract sculptures are made of axes and chains, they are not frightful, nor do they try to be. They are just simple, lovely objects.

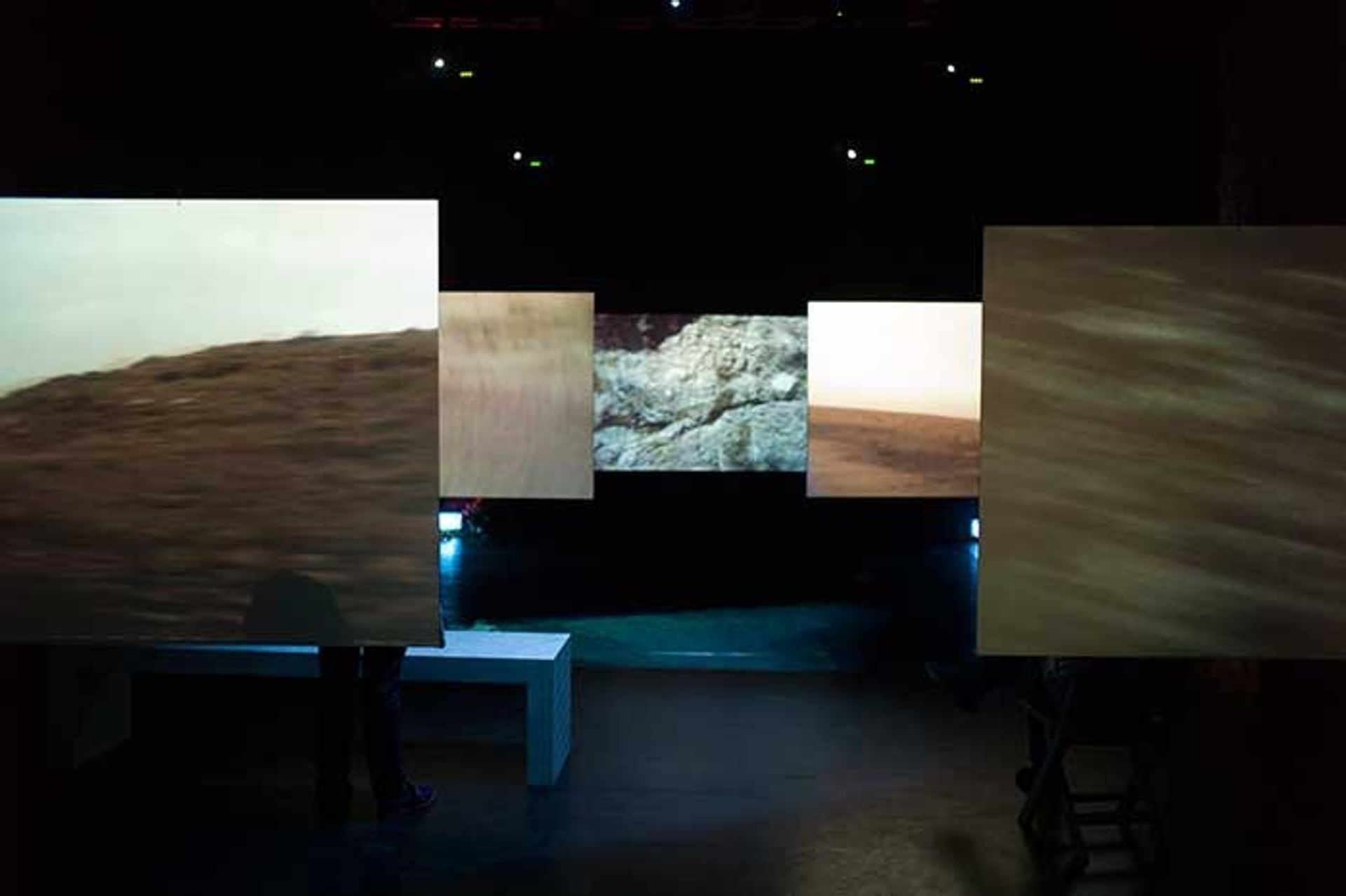

But lovely objects are made invisible in a show that also includes Chantal Akerman’s abrasive and petrifying installation Now (2015). In a small room made smaller by the blistering soundtrack of trucks driving across a desert, Akerman has staged five screens that play disorienting film footage of the trip. Random gunshots and muffled shouts pierce the noise and the room pulsates in cacophony, but it is impossible to tell exactly what is going on. Violence is always baffling.

There is quiet violence too. Steve McQueen’s beautiful film Ashes (2014-15), in which a chiseled young man sails silently aboard a small ship off the coast of Grenada, works exactly in the opposite direction of Akerman’s installation. Everything about McQueen’s piece is serene: the setting, the cinematography, the handsome main actor. But the movie is punctured, at the very end, by an abrupt, painful ending. During a brief voiceover, we learn from a friend of Ashes that this young man was murdered by drug dealers after the film was made: “he tried to run and they shoot him in the back and when he fell, one of them guys went over to him and shot him up around his belly and his legs and thing.”

Work like this is pulverizing. It cuts analysis short and neither Marx nor Enwezor can explain its aesthetic impact. But it still raises inevitable moral questions; violence always does. There is no easy tie between aesthetics and ethics (as Enwezor shrewdly writes in the catalogue, “art has no obligation. It can always choose to stay silent, deaf to all appeals for social awareness and critical engagement”) but Harold Bloom is right, when he remarks in The Anxiety of Influence, that strong poets “should always be condemned by humanist morality, for strong poets necessarily are perverse”. Great art, he insists, “is built upon the ruin of every impulse most generous in us.”

It should frighten us that the cruelest work in Venice is also the most riveting. In that sense, Russeth is correct to say that “if anyone tells you this was their favorite biennale, worry about their emotional state.” But emotions should not be denied, and the beauty of brutality cannot be ignored because of its moral inconvenience. We have always been drawn to violence. It has always had an aesthetic appeal. When the Romantics made violence an artistic virtue in the early 19th century, they were only emphasising what we already knew. (What is more beautiful or more horrible than Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, 1818-19?) Art has only one obligation: to honestly stir sensibility. Sometimes it does so by inducing horror, but so long as it affects the imagination; so long as it swallows our awareness and refuses to be explained; so long as it exceeds our linguistic capacities, art succeeds.

Yet however brutal the best work in the biennale, real violence would quickly wash it away; real violence always threatens to undercut our achievements. In a beautiful gallery devoted to the work of Fabio Mauri and Adrian Piper, there is towering photograph of Adolph Hitler’s Reich Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, at the Degenerate Art Show of 1937, surrounded by enthusiastic Nazis. The piece—part of Mauri's installation Evil Numbers (1978)—is a reminder that there is nothing abstract about cruelty. It has a long and vicious history. In art, it can give perverse pleasure. But in life, it is only a terrible possibility. Across from the photograph are numerous chalkboards on which Piper has written a haunting refrain, which is precisely the threat that violence always makes: “everything will be taken away.”

All the World’s Futures, Venice Biennale, until 22 November

This article has been updated to clarify that a picture of Joseph Goebbels is part of an installation by Fabio Mauri, not Adrian Piper.